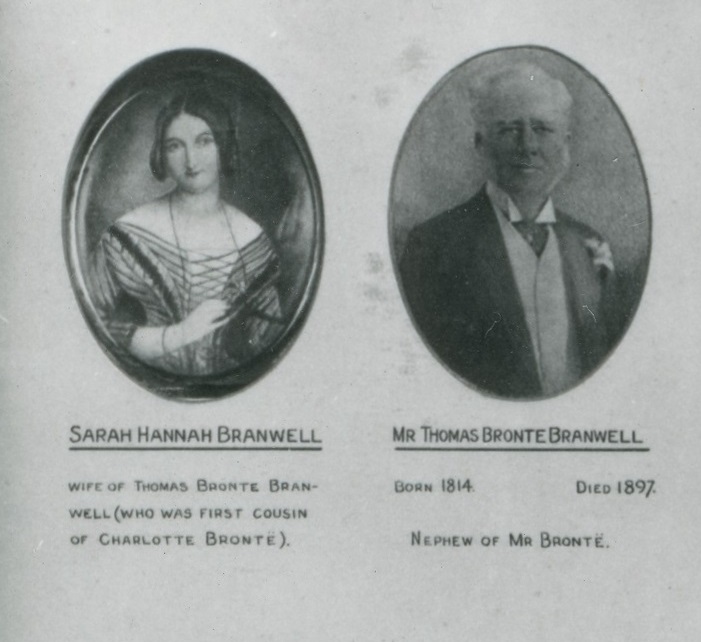

The last week or so has seen a plethora of Brontë related births and baptisms. As we saw in the previous post, it was Maria Branwell’s birthday on 15th April. 20th April saw the birthday of Ellen Nussey, born in 1817, whilst 22nd April was the birthday of longtime Brontë servant Martha Brown, born in 1828. The 23rd April was the anniversary of the 1814 baptism of Maria Brontë, the eldest Brontë sibling, although her date of birth is unknown. In today’s post, however, we take a special birthday look at a woman whose special day was sandwiched by that of Ellen and Martha: Charlotte Brontë, whose 205th birthday fell on Wednesday of this week.

What can we say about Charlotte Brontë? She is one of the leading novelists of all time, a fine poet and a great letter writer. What did those who knew Charlotte Brontë say about her? Let’s take a look:

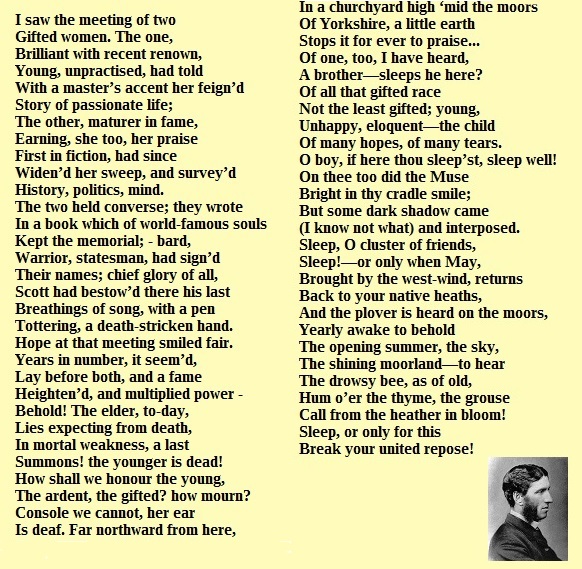

Matthew Arnold

‘I talked to Miss Brontë (past thirty and plain, with expressive grey eyes, though) of her curates, of French novels, and her education a school at Brussels.’

Arnold was a poet and critic who later wrote an elegy to the Brontes, ‘Haworth Churchyard’.

George Smith

‘Charlotte Brontë stayed with us several times. The utmost was, of course, done to entertain and please her. We arranged for dinner-parties, at which artistic and literary notabilities, whom she wished to meet, were present. We took her to places which we thought would interest her – The Times office, the General Post Office, the Bank of England, Newgate, Bedlam. At Newgate she rapidly fixed her attention on an individual prisoner. This was a poor girl with an interesting face, and an expression of the deepest misery. She had, I believe, killed her illegitimate child. Miss Brontë walked up to her, took her hand, and began to talk to her. She was, of course, quickly interrupted by the prison warder with the formula, ‘Visitors are not allowed to speak to the prisoners.’ Sir David Brewster took her round the Great Exhibition, and made the visit a very interesting one to her. One thing which impressed her very much was the lighted rooms of the newspaper offices in Fleet Street and the Strand, as we drove home in the middle of the night from some City expedition.

On one occasion I took Miss Brontë to the Ladies Gallery of the House of Commons. The Ladies’ Gallery of those days was behind the Strangers’ Gallery, and from it one could see the eyes of the ladies above, nothing more. I told Miss Brontë that if she felt tired and wished to go away, she had only to look at me – I should know by the expression of her eyes what she meant – and that I would come round for her. After a time I looked and looked. There were many eyes, they all seemed to be flashing signals to me, but much as I admired Miss Brontë’s eyes I could not distinguish them from the others. I looked so earnestly from one pair of eyes to another that I am afraid that more than one lady must have regarded me as a rather impudent fellow. At length I went round and took my lady away. I expressed my hope that I did not keep her long waiting, and said something about the difficulty of getting out after I saw her signal. ‘I made no signal,’ she said. ‘I did not wish to come away. Perhaps there were other signals from the Gallery.’

Miss Brontë and her father had a passionate admiration for the Duke of Wellington, and I took her to the Chapel Royal, St. James’s, which he generally attended on Sunday, in order that she might see him. We followed him out of the Chapel, and I indulged Miss Brontë by so arranging our walk that she met him twice on his way to Apsley House. I also took her to a Friends’ meeting-house in St. Martin’s Court, Leicester Square. I am afraid this form of worship afforded her more amusement than edification.’

Smith, although Charlotte’s publisher and a successful businessman, was eight years younger than Charlotte Brontë. They became great friends, and it’s believed that the character of Graham Bretton in Villette is based on him.

Abraham Holroyd

‘As to Miss Charlotte Brontë, I never saw to her to speak to but once. It was in the summer of 1853. I had sometime before returned from a sixteen years’ absence from home, and, while residing in the souther part of the United States, I met with and read her ‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Shirley.’ So, led by curiosity, I one Sunday went to Haworth, with the desire to see the author of such remarkable works. I was late in arriving at the church, and found a pale young man reading the morning service – I think it was Mr G. de Renzy. Mr Brontë was also in the pulpit, for I knew him at once, having seen him before during my childhood at Thornton Church. The sexton, Mr Brown, had given me a very good place for seeing every one in the lower part of the church, and during the singing of the hymn before the sermon, my eyes wandered off in search of the person I had come to see. Face after face I scanned, until at length, in a large square pew near the communion table and under the organ, I saw ‘Jane Eyre,’ or, rather, I should say, Charlotte Brontë. I had not a doubt of it, for there was not such another face in the whole church; and I called to mind the following conversation in the novel where ‘Jane Eyre’ lies in a state of prostration at Mr St. John’s:-

“She is so ill, St. John.”

“Ill or well, she would always be plain. The grace and harmony of beauty are quite wanting in those features.”

And yet there was great breadth and volume in her forehead; some resemblance to the portraits of Miss Harriet Martineau, I thought, might also be traced. The cheek-bones appeared to me rather prominent, but the entire face gave me the idea that she had much goodness and gentleness of disposition, and possibly great power over those with whom she might come in contact. Her dress was very plain. It was a gown without any flounce, and had plain narrow sleeves. Over her shoulders was thrown a velvet cape – also very plain. Her bonnet was neat in appearance, but not in the fashion.’

Abraham Holroyd was a local historian of some repute in Bradford in the late ninenteenth century, and he also ran a bookshop in Thornton.

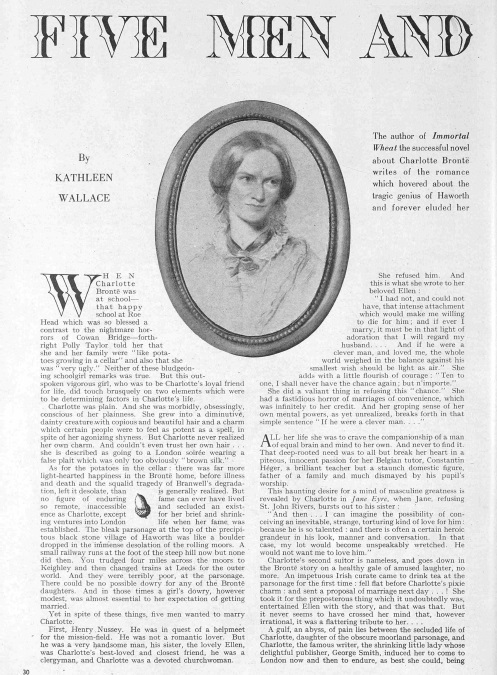

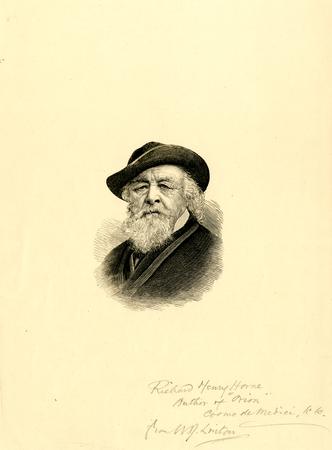

Richard Hengist Horne

‘A fragile form is now before my minds eye as distinctly as it was in reality more than twenty years ago! The slender figure is seated by a fire in the drawing-room of Mr G. S., the publisher of a novel which had brought the authoress at one bound to the top of popular admiration. There has been a dinner-party, and all the literary men whom the lady had expressed a wish to meet, had been requested to respect the Publisher’s desire, and the lady’s desire that she should remain ‘unknown’ as to her public position. Nobody was to know that this was the authoress of ‘Jane Eyre’. She was simply Miss Brontë on a visit to the family of her host. The dinner-party went off as gaily as could be expected where several people are afraid of each other without knowing why, and Miss Brontë sat very modestly and rather on her guard, but quietly taking measure of les monstres de talent, who were talking and taking wine, and sometimes bantering each other. Once only she issued from her shell, with brightening looks, when somebody made a slightly disparaging remark concerning the Duke of Wellington, for whom Miss Brontë declared she had the highest admiration; and she appeared quite ready to do battle with one gentleman who smilingly suggested that perhaps it was “because the Duke was an Irishman”….

‘A very gentle, brave, and noble spirited woman was Charlotte Brontë. Fragile of form, and tremulous as an aspen leaf, she had an energy of mind, and a heroism of character capable of real things in private life, as admirable as any of the fine delineations in her works of fiction.’

Richard Hengist Horne, a one time mercenary, was a popular writer of the time, most noted for his long poem Orion which was much admired by Charlotte.

James Chesterton Bradley

‘All the three sisters were very shy, but perhaps Emily and Anne were worse than Charlotte in that respect. The latter, as I remember her, was a lively talker when once drawn out, a girl of about ordinary stature, or perhaps below it, with features neither very dark nor fair, but with striking expressive eyes and mouth. She had a particular way of suddenly lifting her eyes and looking straight at you with a quick, searching glance whilst you spoke to her.’

Reverend Bradley was curate of nearby Oakworth; noted for playing a flute, he was immortalised by Charlotte as the flute playing Reverend David Sweeting in Shirley.

Elizabeth Gaskell

‘Miss Brontë I like… She is very little & very plain. Her stunted appearance she ascribes to the scanty supply of food she had as a growing girl, when at that school of the Daughters of the Clergy… She is truth itself, and of a very noble sterling nature, which has never been called out by anything kind or genial… She is very silent & very shy; and when she speaks chiefly remarkable for the admirable use she makes of simple words, & the way in which she makes language express her ideas. She and I quarrelled and differed about almost every thing, – she calls me a democrat, & can not bear Tennyson – but we like each other heartily I think & I hope we shall ripen into friends.’

This was Gaskell’s opinion after her first meeting with Charlotte in August 1850. They did indeed become friends, and Elizabeth paid tribute to Charlotte in her The Life Of Charlotte Brontë.

John Robinson

‘Charlotte Brontë also took an interest in the needlework of the school, and was the principal support of the girls’ Sunday school, and so much was she beloved by those in her class that many remained in attendance at the Sunday school long after their marriage, even when they had children attending the lower classes at the school… I often watched Miss Brontë when examining the work of the girls in the needlework classes, and also watched her from the Church tower when she was sitting at her writing-desk in the little room over the top of the front door at the parsonage. It was always necessary for her, on account of her short-sightedness, to have her face within a very few inches of the paper.’

John Robinson of Haworth was being trained to be a teacher by Arthur Bell Nicholls at the time of his marriage to Charlotte Brontë. He was present at their wedding, and gave a very moving and fulsome account of it.

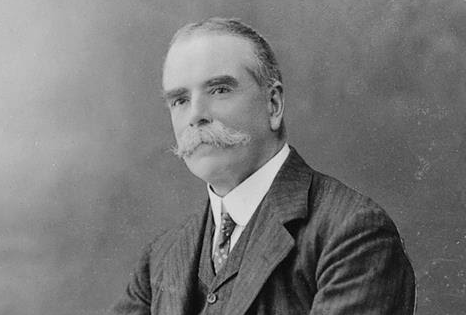

Sir James Roberts BT

‘I heard Mr Brontë preach, and remember him as a man most tolerant to divergencies of religious conviction. Above all these memorabilia there rises before me the frail and unforgettable figure of Charlotte Brontë, who more than once stopped to speak a kindly word to the little lad who now stands a patriarch before you. These early associations, still very dear to me, were followed in after years by exceeding delight in those creations of imaginative genius which Charlotte and her sisters have left to us.’

James Roberts vividly remembered his encounters with Charlotte Brontë when he was a young Haworth boy; little could she have known what a part he would play in preserving her legacy. Roberts became a successful and wealthy businessman, and was made a Baronet. It was he who purchased Haworth Parsonage from the Church of England and gifted it to the Brontë Society to house their museum in.

Finally let’s close with the accounts of a person who knew Charlotte perhaps better than anyone, and who, but for a few hours, almost shared a birthday with her:

Ellen Nussey

‘Turning to the window to observe the look-out I became aware for the first that I was not alone; there was a silent, weeping, dark little figure in the large bay window; she must, I thought, have risen from the floor. As soon as I had recovered from my surprise, I went from the far end of the room, where the book-shelves were, the contents of which I must have contemplated with a little awe in anticipation of coming studies. A crimson cloth covered the long table down the centre of the room, which helped, no doubt, to hide the shrinking little figure from my view. I was touched and troubled at once to see her so sad and tearful…

‘She never shirked a duty because it was irksome, or advised another to do what she herself did not fully count the cost of doing, above all, when her goodness was not of the stand-still order, when there was new beauty, when there were new developments and growths of goodness to admire and attract in every succeeding renewal of intercourse, when daily she was a Christian heroine, who bore her cross with the firmness of a martyr-saint…

‘She was so painfully shy she could not bear any special notice. One day, on being led into dinner by a stranger, she trembled and nearly burst into tears; but not withstanding her excessive shyness, which was often painful to others as well as to herself, she won the respect and affection of all who had opportunity enough to become acquainted with her. Charlotte’s shyness did not arise, I am sure, either from vanity or self-consciousness, as some suppose shyness to arise; its source was in her not being understood. She felt herself apart from others; they did not understand her, and she keenly felt the distance.’

What is clear is that Charlotte Brontë was small, she was shy, but above all she was kind and loving, and much loved in return by people of all social classes. You can find many more first person encounters with Charlotte and her sisters on this blog and in my book Crave The Rose: Anne Brontë At 200. I hope you can join me again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post, and in the meantime let’s say a belated Happy Birthday, Charlotte Brontë!