I had a long and fulsome post planned for today’s Brontë blog, but unfortunately life throws us curve balls sometimes. A family emergency has thrown my plans, hopefully temporarily, into turmoil, and so today’s post will be shorter than usual – I hope you don’t mind too much and that you still find it interesting; in today’s post we look at a steadfast defence of the Brontës from a man who knew them well: William Dearden.

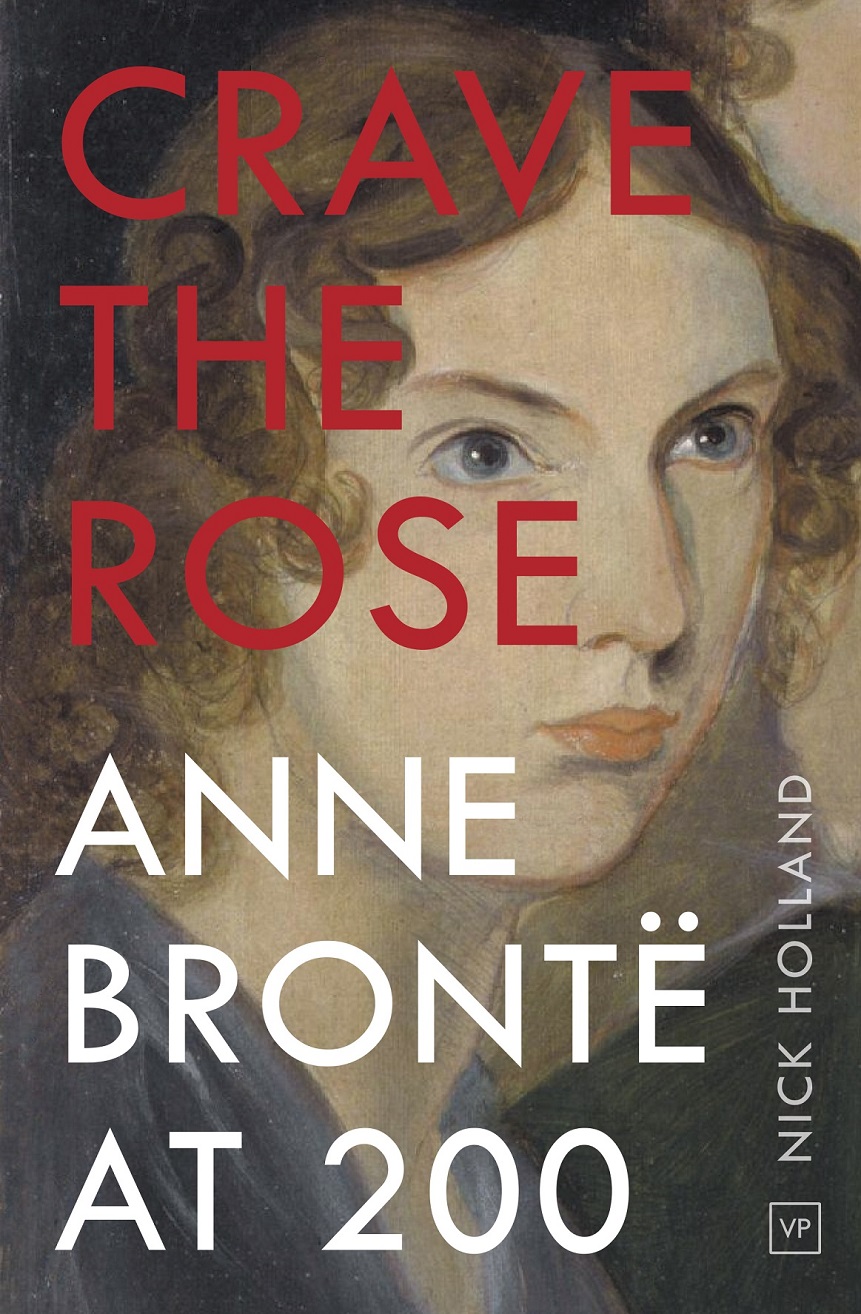

The account of the Brontë family also appears in my recent book Crave The Rose: Anne Brontë at 200 published by Valley Press. The book features a concise biography of Anne Brontë, along with a never before published in book form essay which I believe is Anne’s final written work, and then a selection of first person accounts of meetings with the Brontës – the section I particularly love, as it lets us see the Brontës as they were in everyday life. Valley Press, based in Anne’s beloved Scarborough, have found times tough during the pandemic, as have many small publishers, so if you head over to their website and make a purchase from them (it doesn’t have to be my book of course) I’m sure they would be grateful.

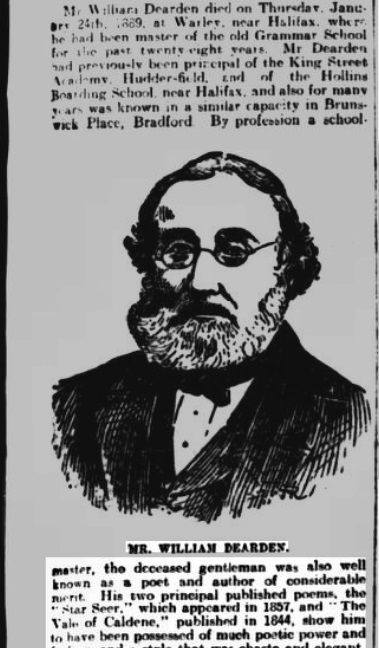

Before we look at this particular account, let’s look briefly at who William Dearden was. Dearden was a schoolmaster whose long career had seen him take charge at schools in Huddersfield, Bradford, Keighley and Halifax, where he was for 28 years master of the Grammar School. He was also a poet who received some acclaim in his day, with his works ‘The Vale of Caldene’ (1844) and ‘The Star-Seer’ (1837) particularly well received. It has to be said that the style of the latter is a little over-wrought, but his ambition can’t be doubted in this epic fantasy poem spanning well over a hundred pages followed by seventy pages of notes. Here’s a typical extract:

‘The MAGIAN waves his hand: the elf retires:

Now, while above him, play the livid fires.

And roars the hollow thunder, from its home

Of adamant, the SEER the Fatal Tome

Lifts high in air; then, with his bloody blade.

Severs the curse-denouncing, golden braid;

And thus, erect, with upturned gaze, he cries.

While from the last leaf’s awful mysteries

He tears the final seal, “Dark fiends! let fall

Your utmost vengeance! I will brave it all!”

Dread sight! from out the north, whose swarthy brow

Begins to show an ashy paleness now.

Descends a flash, which, like an arm of fire,

Launched from the riven clouds, with thunderings dire.

Smites down the SEER, and, in his blasted hand.

Consumes the Book of Fate! As from a land

Of everlasting winter, issue forth

From the oped portal of the gleaming north,

Cloud-charioted, and fast-careering on.

Two shapes, on whom no summer ever shone!

Their visages are thin, and ghastly pale;

Dim are their eyes, as ne’er to close, yet fail

Through infinite watching; and their lips are sealed

Close, as for ages they had not revealed

Aught save a sigh!’

More pertinently for us, Dearden became a close friend of Branwell Brontë and then of the family as a whole. He was nothing if not loyal to their memory; after the publication of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë he wrote a string of letters to local newspapers attempting to correct some of the errors he saw in it. So regular and strident were these letters that at one point Patrick Brontë himself wrote to Dearden asking him to stop writing them.

William Dearden was undeterred however, as this extract from his letter published in the Bradford Observer on 27th June 1861 shows. Written less than a month after Patrick Brontë’s death, it’s a very interesting account of the Brontë family, if a partial one:

‘It is a duty I owe to the memory of my late venerable friend, and in fulfilment of a sacred promise, to place his character in a true light before the world; and this is the more imperatively necessary, because – though Mrs Gaskell has, in her later editions of Charlotte Brontë’s life, toned down some of its harsher features in obedience to conviction of their distortion and untruthfulness – it still stands prominently forth in repulsive stoical sternness and misanthropical gloom. My acquaintance with Mr Brontë extends over a long series of years. In the early portion of that acquaintanceship, I had frequent opportunities of seeing him surrounded by his young family at the fireside of his solitary abode, in his wanderings on the hills, and in his visits to Keighley friends. On these occasions, he invariably displayed the greatest kindness and affability, and a most anxious desire to promote the happiness and improvement of his children. This testimony, it is presumed, will have some weight, especially with whose who wish to form a correct estimate of human character.

It will be remembered that Mr Brontë’s children were deprived of their mother when they were at a very tender age. We are led to infer from Mrs Gaskell’s narrative, that their father – if he felt – at least did not manifest much anxiety about their physical and mental welfare; and we are told that the eldest of the motherless group, then at home, by a sort of premature inspiration, under the feeble wing of a maiden aunt, undertook their almost entire supervision. Branwell – with whom I was on terms of literary intimacy long before his fatal lapse – told me, when accidentally alluding to this painful period of in the history of his family, that his father watched over his little bereaved flock with truly paternal solicitude and affection – that he was their constant guardian and instructor – and that he took a lively interest in all their innocent amusements. Such – before the blight of disgrace fell upon him – is the testimony of Branwell to the domestic conduct of his father. “Alas!” said he to me, many years after that sad event, “had I been what my father earnestly wished and strove to make me, I should not have been the wreck you see me now!” Poor Branwell! May his sad example prove a warning to others to shun the gulf of misery into which he was prematurely plunged! If Mr Brontë had been the cold indifferent stoic he has been represented, the perpetual outflow of love and tenderness in regard to him from the hearts of his children, could not have been naturally expected. An unfeeling father ought not to complain, if he reaps but a scanty harvest of filial duty and affection in return for what he has sown. Love begets love – a saying not the less true, because it is trite.

As Mr Brontë’s children grew up, he afforded them every opportunity his limited means would allow of gratifying their tastes either in literature or the fine arts; and many times do I remember meeting him, little Charlotte, and Branwell, in the studio of the late John Bradley, at Keighley, where they hung with close-gazing inspection and silent admiration over some fresh production of the artist’s genius. Branwell was a pupil of Bradley’s, and, though some of his drawings were creditable and displayed good taste, he would never, I think, on account of his defective vision, have become a first-rate artist. In some departments of literature, and especially in poetry of a highly imaginative kind, he would have excelled…

The cold stoicism attributed to Mr Brontë was apparent only to those who knew him least; beneath this “seeming cloud” beat a heart of the deepest emotions, the effects of whose outflowings, like the waters of a placid hidden brook, were more perceptible in the verdure that marked their course than in the voice they uttered. God, and the objects to whom that good heart swelled forth in loving kindness – and the latter only, perhaps, very imperfectly – know the depth and intensity of its emotions. He was not a prater of good words, but a doer of them, for God’s inspection, not man’s approbation. Every honest appeal to his sympathy met a ready response. The needy never went empty away from his presence, nor the broken in spirit without consolation.’

May we all have friends like William Dearden to defend us when the hour comes. And, may I see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.

Good luck and thanks you for your fascinating blog posts.

I hope your family emergency is not serious and everything goes back to normal soon! Best wishes to you and your family – your blog posts have helped me many times during my own familial troubles and I am very grateful for that!

Thank you so much Lara!