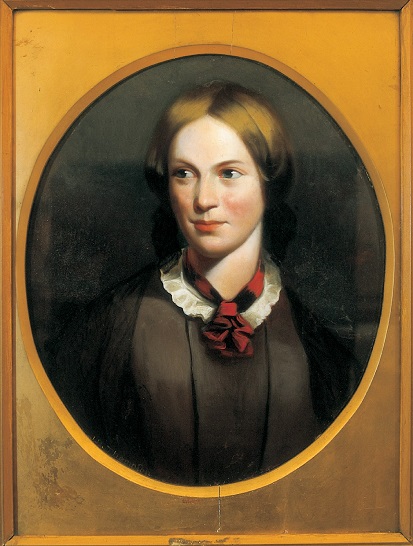

Charlotte Brontë was not a woman who was content to sit and do nothing; rather, she was a woman of action who liked to occupy her time in the best possible way. This day in 1850 must have been difficult for her, because it was on this day, the 13th of June, that she sat, for the first time, for the portrait artist George Richmond. In today’s post we’re going to look at that portrait of Charlotte Brontë, and at others she had done.

As I said, this is the 171st anniversary of Charlotte’s first sitting for Richmond at the home of her London publisher George Smith, she also sat for him on the 15th June and 24th June before her portrait was complete. We can imagine the thoughts whizzing through Charlotte’s mind as she sat in stillness and silence; perhaps her mind turned to future works, to her father in Haworth, or to her recently departed siblings? At least she would have found some comfort in the fact that she was being drawn by one of the leading society portraitists of his day.

Richmond, born in 1809, was known for his portraits in chalk, and he was so much in demand that he often had three or four subjects sitting for him in one day. After three sittings, two at the Smith house near Hyde Park, and the final one at the Phillimore Gardens home of Charlotte’s friend Laetitia Wheelwright, the portrait was complete, and it remains the definitive image of Charlotte Brontë to this day.

What did people who knew Charlotte well think of the portrait? In a letter to Ellen Nussey of 1st August 1850, Charlotte made these comments:

‘My portrait is come from London – and the Duke of Wellington’s and kind letters enough. Papa thinks the portrait looks older than I do: he says the features are far from flattered, but acknowledges that the expression is wonderfully good and life-like.’

On the other hand the ever frank Mary Taylor said that the portrait was ‘too much flattered’, whilst Ellen Nussey herself remarked that ‘there would always have been regret for its painful expression to be perpetuated.’ It’s said that faithful servant Tabby Aykroyd didn’t like the picture at all, although it has to be said that Tabby was only partially sighted by this time. Perhaps the problem was that George Richmond created so many portraits, and stuck rigidly to his own style, that many people said that his portraits all looked similar.

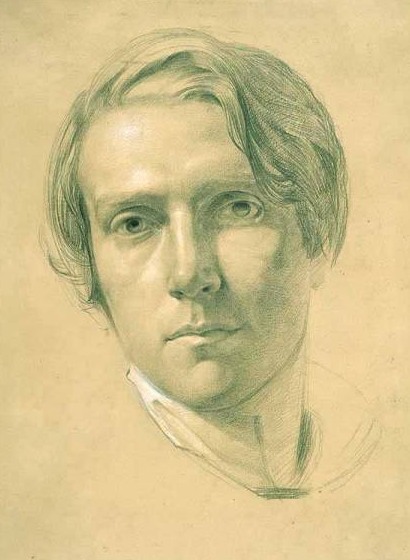

This rather lovely portrait of Charlotte Brontë was painted by John Hunter Thompson, but if Mary Taylor thought the Richmond portrait was flattering, who knows what she would have thought of Thompson’s? This portrait is now part of the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection, but it was one that Charlotte never sat for.

We don’t know the exact date of this composition, so does the fact that it was not painted from life make it worthless? Not necessarily, for Thompson was a great friend of Branwell Brontë, and it’s likely that he had met Charlotte Brontë too.

In fact, J.H. Thompson was not only a friend of Branwell’s, but a colleague too. He was a fellow portrait artist in Bradford at the time Branwell was painting there, and we know that Thompson was occasionally called upon by Branwell to put the finishing touches to paintings he’d worked on. Painted from memory it may be, but Thompson certainly gives Charlotte Brontë a happier, more vibrant, disposition than Richmond managed.

Talking of Branwell, we have his teenage portrait of his sisters Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë of course. It’s less complete than the other portraits we have of Charlotte, but it’s also surely the most important as it was painted by someone who was part of her daily life.

The story is well known of how he painted himself into the portrait but was so dissatisfied at this part of the portrait that he painted himself out by placing a large pillar over his own image. It’s a great metaphor for the impression that Branwell would make on life compared to his sisters, but is it true? Certainly someone was painted out, but the man in the faded image seems to be wearing a large neck warmer known as a Wellington. These were habitually worn by Patrick Brontë, as we see in all his pictures, so could the ghostly figure behind the pillar actually have been Branwell’s father? After all, if Branwell was looking at the quartet as he painted it, he couldn’t also have been part of it.

There is another portrait to look at. This beautiful image was once believed to be of Charlotte Brontë, painted in Belgium in 1843 by her friend Mary Dixon, a cousin of Mary Taylor. Dixon became a great friend of Charlotte’s in Brussels, although she was in such ill health that Charlotte referred to her as ‘a piteous case’, and said that it was ‘grievous to think of her.’ Despite her illness, however, Mary Dixon died in 1897 aged 88.

The picture was bought by the Brontë Society in 2002, but it’s subject matter is now thought not to be Charlotte Brontë. Just as with its initial attribution, however, that is unproven, so could it be Charlotte after all? In addition to this we have the Edwin Landseer portrait which is believed by some to be a portrait of the Brontë sisters.

We almost had another Charlotte Brontë portrait, by an artist whose name is still renowned across the world: John Everett Millais, the founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. A young Millais was struck by Charlotte Brontë after meeting her in London at a party hosted by Thackeray. Millais later told his daughter that Charlotte forever represented in his mind the ideal of a woman genius, and that she had remarkable eyes; he also stated that Charlotte, ‘looked tired with her own brains.’ Millais offered to paint Charlotte’s portrait, but stepped aside when he learned that Richmond was already underway with a portrait of her.

Perhaps the greatest portraits of all are those of the characters which Charlotte and her family brought to life in her books. I shall see you again next Sunday for another sitting, er, I mean another new Brontë blog post.

As always a very interesting read, thank you Nick!

Fascinating. I always wondered why Branwell would paint himself into a portrait and then paint it out. Interesting to think that it was perhaps his father that was originally in the pillar portrait, which then begs the question: why did he paint him out? I looked up the Edwin Landseer portrait and it certainly looks like it could be the Brontë sisters. They are so enigmatic, I like that we only have glimpses of what they looked like, as their literature is the truest portrait of who they were.

Great post! I’m curious where you found the Millais remark. I’m looking into relationships between artists and writers.

Thanks!

Nick this is super duper- yoo really are a cleva dude! I had No Idea about Millais’ impression or intrigue.. u may lk 2 know he was (frm 1845) Landseer’s protege, completed his Mentor’s unfinshed works 1873. Thompson was B’s fellow student of Robinson, who in turn was RA classmate of Lanny. I agree Thompson’s rendition is true and beautiful. Btw many thanks for mentioning Lanny’s group caption 1838.

Best portrait of Charlotte Brontë

J H Thompson