The Brontës are probably the most famous writing siblings of them all, which will make Grimm reading for two of their rivals, and their work continues to be enjoyed around the globe. Reading a Brontë novel can be moving, cathartic, and thought provoking, and it’s certainly enjoyable, but what did the Brontës think of the writers they read? That’s the subject of today’s new post.

When I say ‘the Brontës’, on this occasion I specifically mean Charlotte Brontë; unfortunately we don’t have the written pronouncements of Anne and Emily on this subject. Nevertheless, they were avid readers and we can see the influence of writers such as Scott in particular on Emily’s novel Wuthering Heights. It was Charlotte who gave her always frank and honest opinions on many of our greatest writers, however, including perhaps the greatest of them all: William Shakespeare.

As an eighteen year old, Charlotte famously wrote of the great bard:

‘If you like poetry let it be first rate, Milton, Shakespeare, Thomson, Goldsmith, Pope (if you will though I don’t admire him), Scott, Byron, Campbell, Wordsworth and Southey. Now Ellen don’t be startled at the names of Shakespeare, and Byron. Both these were great men and their works are like themselves. You will know how to choose the good and avoid the evil, the finest passages are always the purest, the bad are invariably revolting you will never wish to read them over twice. Omit the comedies of Shakespeare.’

It seems, however, that in later years Charlotte had a keen interest in, or at least knowledge of, Shakespeare. We know this from the testimony of a Frank Peel, an aspiring actor who called upon Charlotte Brontë as he didn’t have any boots – Charlotte seemingly being well known in the area for her acts of philanthropy. He got the boots, but he also got a lesson in Shakespeare:

‘By the time I had finished my breakfast the lady had returned to the kitchen and put some old boots before me, bidding me to try to fit a pair on. I did so, and found a pair which fitted pretty well. By this time the younger lady also returned into the kitchen. Both sat down, and Miss Charlotte then said, “I have given you breakfast, found you boots, and I am now going to talk to you a bit.” She did talk to me, and in a way that made me wish I had never gone. She said that in nine cases out of ten people adopted my course of life from sheer idleness or gipsy instinct, and not because they had any special talent for theatricals. Did I think I had any talent? I told her I thought I had. Would I give her a specimen? Here was a dilemma! How could I refuse after the kindness with which I had been treated? In great pain, I said I would try to comply with her request. I gave, first, ‘Young Lochinvar,’ in my best style, and then her look of motherly severity seemed to relax a little. She then began to ask a number of questions about my family and other matters, which I answered as well as I could. Amongst other things, I told her I had relations at Cleckheaton. and described it and the neighbourhood to her. The younger lady then asked me if I knew any more recitations, and I replied I could give one or two from Shakespeare. Feeling more at ease, I at once recited one or two selections from ‘Hamlet’, without any remark being made. Miss Charlotte then asked me if I would give the dialogue between Hamlet and his mother, where the Queen says, “Do not for ever with thy veiled lids seek for thy noble father in the dust; thou know’st ’tis common, all that live must die—passing through nature to eternity.” I complied as well I could; gave the whole scene without the ladies displaying any special interest in it, until I came to the line where Hamlet says, “I have that within which passeth show; these, but the trappings and the suits of woe,” when they both burst out into good-humoured laugh. I dared not ask the cause of this, but I suppose my looks showed my anxiety, and Charlotte said, “I’ve seen Hamlet played at Bradford, and they made the same mistake you have made in the word ‘suite.’ Shakespeare never could have used it in that sense – namely, a dress – but in a wider sense, ‘suite,’ pronounced ‘sweet,’ meaning that the King, Queen, and all about them were only acting the part of mourners, making their conduct match or harmonise with their supposed recent bereavement – the death of Hamlet’s father.” I did not venture on any opinion, but said I believed it was in the book. Miss Charlotte said it was, but only showed the ignorant, shortsightedness of those who tampered with Shakespeare’s works.’

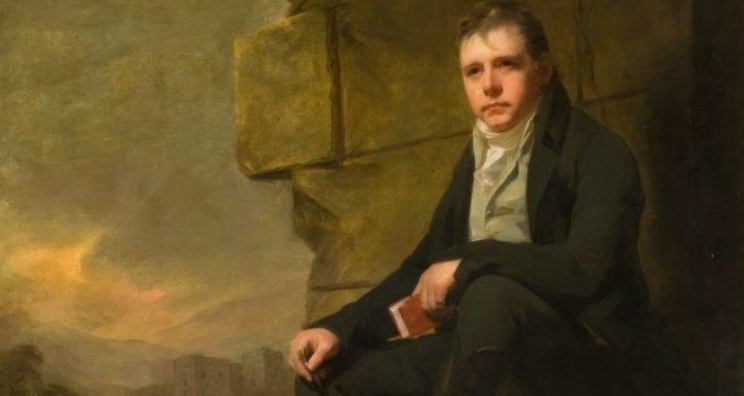

One writer whom Charlotte Brontë always gave a glowing tribute to was Walter Scott. In the first letter we saw, Charlotte praised Scott’s poetry, but in the same 1834 missive she also praised his prose:

‘For Fiction – read Scott alone, all novels after his are worthless.’

By 1848, when Charlotte herself was a published and much praised writer, it was still Scott who held the position of supremacy in her mind, as we see in this letter to W. S. Williams:

‘The standard heroes and heroines of novels, are personages in whom I could never, from childhood upwards, take an interest, believe to be natural, or wish to imitate; were I obliged to copy these characters, I would simply not write at all. Were I obliged to copy any former novelist, even the greatest, even Scott, in anything, I would not write.’

Ask people today to name the greatest writer of ‘classic’ literature, and Jane Austen would be sure to figure highly, but Charlotte Brontë had contrasting views of this brilliant novelist. On 12th January 1848 she wrote the critic G. H. Lewes:

‘’Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point. What induced you to say that you would rather have written Pride & Prejudice or Tom Jones [Henry Fielding] than any of the Waverley novels [by Walter Scott]? I had not seen Pride & Prejudice till I read that sentence of yours, and then I got the book and studied it. And what did I find? An accurate daguerreotyped portrait of a common-place face; a carefully-fenced, highly cultivated garden with neat borders and delicate flowers – but no glance of a bright vivid physiognomy – no open country – no fresh air – no blue hill – no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses.’

This, however, shouldn’t be taken purely as a critique upon Austen. Charlotte had little knowledge of Jane’s writing, and from the letter to Williams we looked at, we can see how Charlotte was determined to differentiate herself from the style and characters of preceding novelists. Two years later, however, Charlotte is expressing praise, in her unique way, for Jane Austen’s Emma:

‘I have likewise read one of Miss Austen’s works Emma – read it with interest and with just the degree of admiration which Miss Austen herself would have thought sensible and suitable – anything like warmth or enthusiasm; anything energetic, poignant, heart-felt, is utterly out of place in commending these works: all such demonstrations the authoress would have met with a well-bred sneer, would have calmly scorned as outré and extravagant. She does her business of delineating the surface of the lives of genteel English people curiously well; there is a Chinese fidelity, a miniature delicacy in the painting: she ruffles her reader by nothing vehement, disturbs him by nothing profound.’

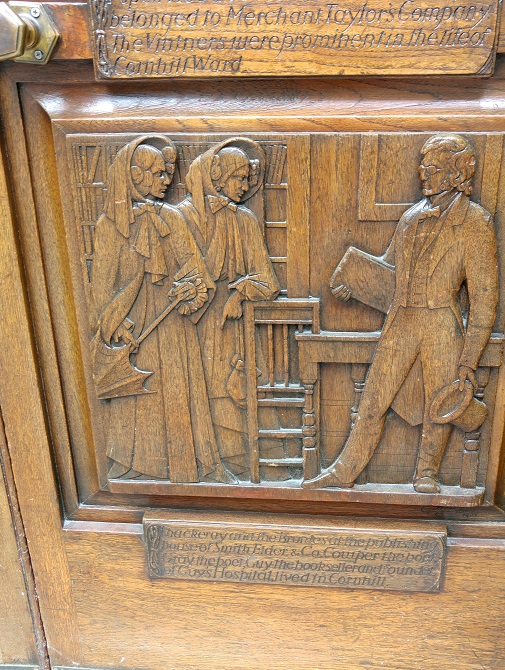

After Scott, perhaps the most enduring literary love of Charlotte was William Makepeace Thackeray. Charlotte dedicated the second edition of Jane Eyre to her hero with extravagantly fulsome praise:

‘There is a man in our own days whose words are not framed to tickle delicate ears: who, to my thinking, comes before the great ones of society, much as the son of Imlah came before the throned Kings of Judah and Israel; and who speaks truth as deep, with a power as prophet-like and as vital-a mien as dauntless and as daring. Is the satirist of “Vanity Fair” admired in high places? I cannot tell; but I think if some of those amongst whom he hurls the Greek fire of his sarcasm, and over whom he flashes the levin-brand of his denunciation, were to take his warnings in time-they or their seed might yet escape a fatal Rimoth-Gilead.

Why have I alluded to this man? I have alluded to him, Reader, because I think I see in him an intellect profounder and more unique than his contemporaries have yet recognised; because I regard him as the first social regenerator of the day-as the very master of that working corps who would restore to rectitude the warped system of things; because I think no commentator on his writings has yet found the comparison that suits him, the terms which rightly characterise his talent. They say he is like Fielding: they talk of his wit, humour, comic powers. He resembles Fielding as an eagle does a vulture: Fielding could stoop on carrion, but Thackeray never does. His wit is bright, his humour attractive, but both bear the same relation to his serious genius that the mere lambent sheet-lightning playing under the edge of the summer-cloud does to the electric death-spark hid in its womb. Finally, I have alluded to Mr. Thackeray, because to him – if he will accept the tribute of a total stranger – I have dedicated this second edition of “JANE EYRE.”’

Thanks to Charlotte’s growing fame, and their shared publisher George Smith, it wasn’t long before she met Thackeray; they got on well, all things considered, despite Thackeray’s large physical size and exuberant character being a sharp contrast to Charlotte herself.

Writing to George Smith in 1852, giving a critique of Henry Esmond (a work in progress by Thackeray which she’d been sent), her praise of the writer is undiminished:

‘Many other things I noticed that, for my part, grieved and exasperated me as I read, but then again came passages so true, so deeply thought, so tenderly felt, one could not help forgiving and admiring…I wish there was one whose word he cared for to bid him good speed – to tell him to go on courageously with the book; he may yet make it the best thing he has ever written… Some people have been in the habit of terming him the second writer of his day; it just depends on himself whether or not these critics shall be justified in their award. He need not be second. God made him second to no man.’

Who then is the number one in popular critical opinion alluded to by Charlotte? It was Charles Dickens, already by 1852 at the age of 40 a national treasure. Perhaps it was a perceived rivalry with Thackeray that led to Charlotte being rather cool on works by Dickens that are now regarded among the greatest novels of all time. In 1852, for example, Charlotte remarked:

‘Is the 1st number of Bleak House generally admired? I liked the Chancery part – but where it passes into the autobiographic form and the young woman who announces that she is not “bright” begins her history – it seems to me too often weak and twaddling; an amiable nature is caricatured not faithfully rendered in Miss Esther Summerson.’

Charlotte Brontë, like her sisters, loved reading books and forming opinions on them; she was a voracious and astute reader. I could fill another dozen posts with her views on other writers including Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, Julia Kavanagh and many more, but I will finish with her October 1852 praise of a contemporary novelist whose work shook society on both sides of the Atlantic, and whose great novel sold more than a million copies in England in that year alone – Harriet Beecher Stowe:

‘I cannot write books handling the topics of the day – it is of no use trying. Nor can I write a book for its moral. Nor can I take up a philanthropic scheme though I honour Philanthropy, and voluntarily and sincerely veil my face before such a mighty subject as that handled in Mrs. Beecher Stowe’s work – Uncle Tom’s Cabin. To manage these great matters rightly they must be long and practically studied – their bearings known intimately and their evils felt genuinely – they must not be taken up as a business-matter and a trading-speculation. I doubt not Mrs. Stowe had felt the iron of slavery enter her heart from childhood upwards long before she ever thought of writing books. The feeling throughout her work is sincere and not got up.’

The bottom line, of course, is that any book is a good book as long as you enjoy reading it. I wish Happy Father’s Day to all fathers out there, and for those for whom this day is a sad one may you find comfort in happy memories. This week also witnessed a sad anniversary for Elizabeth Brontë died on 15th June 1825 aged just ten years old. She was not forgotten then or now.

I leave you all with happier tidings. On Thursday morning I received an email from Sotheby’s – the July auction of the Honresfield Library containing Brontë treasures (and Scott and Austen items) has been suspended. They are instead helping to negotiate a plan to buy the items for the nation, with support from government funds, organisations such as the British Library and the Brontë Parsonage Museum, and from some wealthy philanthropists who are choosing to carry out their good work in private. Charlotte would surely have approved. It’s great news, and it now seems very likely that the items will soon be in public ownership and on view in locations such as Haworth and Euston Road. Many people have messaged me on this, thanks to all and especially to Amber Elby of Texas who has been undertaking fund raising ventures to help bring the Brontës home.

I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post – until then, happy reading!

Thank you Nick for this very informative post.

Good news that the items due for auction may have been saved. Finally, thank you for mentioning Cleckheaton in your post, next door to Red House Gomersal where Charlotte visited her frien, Mary Taylor.

That is truly good news, that priceless Bronte items will be available for public view instead of being squirreled away for private ‘contemplation’.

What about the Brontes and other early 19th C. writers such as Keats, Shelley, Coleridge. Their absence is a glaring deficiency which no one has explained except perhaps that these writers had not ‘penetrated’ to Haworth. I am particularly interested bc the Romantic poets are so near (or in) the Bronte canon/

When assessing Charlotte, it is useful to remember that she is very much the Victorian englishwoman;- prizing ‘muscularity’ and dominance over more ‘female’ qualities or sensibilities. No wonder she can’t appreciate Austen; who wrote in a key so different from Charlotte’s expression. I wonder whether Anne shared her sisters predilections. As always, many thanks for your great blog!