Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë has rightly taken its place in the canon of great works of literature. It was loved from the moment it was published in 1847, but whilst the public took the novel to their hearts, some of the snootier critics weren’t always so impressed (it has ever been thus). In a previous post we looked at Elizabeth Rigby’s incredibly unperceptive take on the novel, but today we’re going to look at a Jane Eyre pronouncement from someone Charlotte knew well: Mary Taylor.

Charlotte Brontë and Mary Taylor were very close friends from the moment they met at Roe Head school in 1831. By the time of Jane Eyre’s publication in late 1847, however, they were over 11,000 miles apart. Mary Taylor emigrated to New Zealand in March 1845, following the path of her brother Waring Taylor who had moved there three years earlier. In a letter of October 1844, Charlotte Brontë revealed the news of Mary’s plans to their mutual friend Ellen Nussey:

‘Mary Taylor is going to leave our hemisphere. To me it is something as if a great planet fell out of the sky. Yet unless she marries in New Zealand she will not stay there long.’

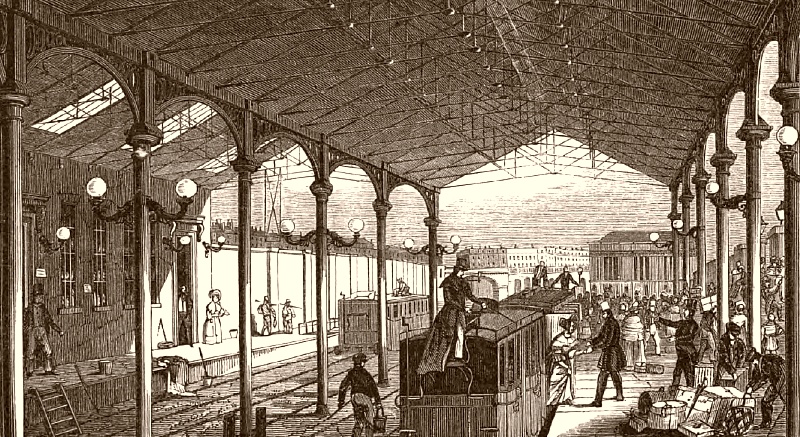

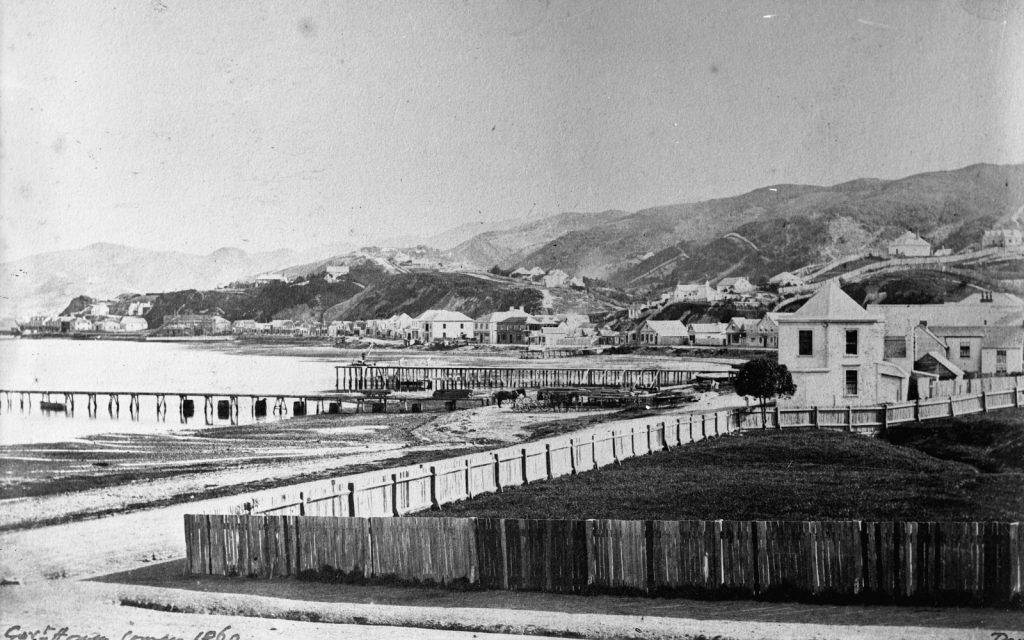

Mary, as Charlotte surely knew, was not the marrying kind, but she was a determined and entrepreneurial woman, and she remained in New Zealand running a successful business until 1859. Being in New Zealand then meant that communication with England was difficult, with letters and parcels taking weeks or months to reach their destination. Nevertheless Mary did keep up correspondence with Charlotte, Ellen and others, and so it was that Charlotte Brontë sent Mary a copy of Jane Eyre written under her pseudonym of Currer Bell.

Unfortunately we don’t have Charlotte’s original letter, sent with the book, to Mary, but we do have Mary’s response to it. She began writing it in June 1848, and completed and sent it on July 24th due to the difficulty in sending mail at the time – as we shall see. Here is Mary Taylor’s letter containing her opinion on Jane Eyre and more:

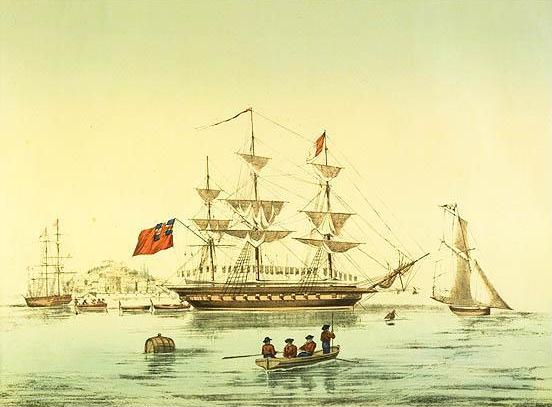

‘Dear Charlotte, About a month since I received and read Jane Eyre. It seemed to me incredible that you had actually written a book. Such events did not happen while I was in England. I begin to believe in your existence much as I do in Mr. Rochester’s. In a believing mood I don’t doubt either of them. After I had read ‘it’ I went to the top of Mt. Victoria & looked for a ship to carry a letter to you. There was a little thing with one mast, & also H.M.S. Fly & nothing else. If a cattle vessel came from Sydney she would probably return in a few days & would take a mail, but we have had east wind for a month & nothing can come in – ‘July 1’ The Harlequin has just come from Otago and is to sail for Singapore when the wind changes & by that route (which I hope to take myself sometime) I send you this. Much good may it do you.

Your novel surprised me by being so perfect as a work of art. I expected something more changeable & unfinished. You have polished to some purpose. If I were to do so I should get tired & weary every one else in about two pages. No sign of this weariness is in your book – you must have had abundance, having kept it all to yourself!

You are very different from me in having no doctrine to preach. It is impossible to squeeze a moral out of your production. Has the world gone so well with you that you have no protest to make against its absurdities? Did you never sneer or declaim in your first sketches? I will scold you well when I see you. I don’t believe in Mr Rivers. There are no good men of the Brocklehurst species. A missionary either goes into his office for a piece of bread, or he goes from enthusiasm, & that is both too good & too bad a quality for St. John. It’s a bit of your absurd charity to believe in such a man. You have done wisely in choosing to imagine a high class of readers. You never stop to explain or defend anything & never seem bothered with the idea – if Mrs. Fairfax or any other well intentioned fool gets hold of this what will she think? And yet you know the world is made up of such, & worse.

Once more, how you have written through 3 vols. without declaring war to the knife against a few absurd doctrines each of which is supported by a “large and respectable class of readers”? Emily seems to have had such a class in her eye when she wrote that strange thing Wuthering Heights. Ann [sic.] too stops repeatedly to preach commonplace truths. She has had a still lower class in her mind’s eye. Emily seems to have followed the bookseller’s advice. As to the price you got it was certainly Jewish. But what could the people do? If they had asked you to fix it, do you know yourself how many cyphers your sums would have had? And how should they know better? And if they did, that’s the knowledge they get their living by. If I were in your place the idea of being bound in the sale of 2! more would prevent me from ever writing again. Yet you are probably now busy with another. It is curious for me to see among the letters one from Aunt Sarah sending a copy of a whole article on the currency question written by Fonblanque! I exceedingly regret having burnt your letters in a fit of caution , & I’ve forgotten about the names. Was the reader Albert Smith? What do they all think of you? I perceive I’ve betrayed my habit of only writing on one side of the paper. Go onto the next page.

I mention the book to no one & hear no opinions. I lend it a good deal because it’s a novel & it’s as good as another! They say it “makes them cry”. They are not literary enough to give an opinion. If ever I hear one I’ll embalm it for you.

As to my own affair I have written 100 pages & lately 50 more. It’s no use writing faster. I get so disgusted I can do nothing. I have sent 3 or 4 things to Joe for Tait. Troup (Ed.) never acknowledges them though he promised either to pay or send them back. Joe sent one to Chambers who thought it unsuitable in which I agree with them…

I have now told you everything I can think of except that the cat’s on the table & that I’m going to borrow a new book to read. No less than an account of all the systems of philosophy of modern Europe. I have lately met with a wonder, a man who thinks Jane Eyre would have done better to marry Mr Rivers! He gives no reasons – such people never do. Mary Taylor’

I have missed out the long middle section dealing with Mary’s life in New Zealand in which she talks about the price of cows and her dream of buying and riding a horse, among many other things. What we have above, though, is a fascinating glimpse into Mary’s mind, her friendship with Charlotte and her views on Jane Eyre.

At first, some of Mary’s opinions may seem a little harsh, but she shared with Charlotte a complete forthrightness and a determination to give an honest opinion in all things, not to mention a sometimes waspish way with words.

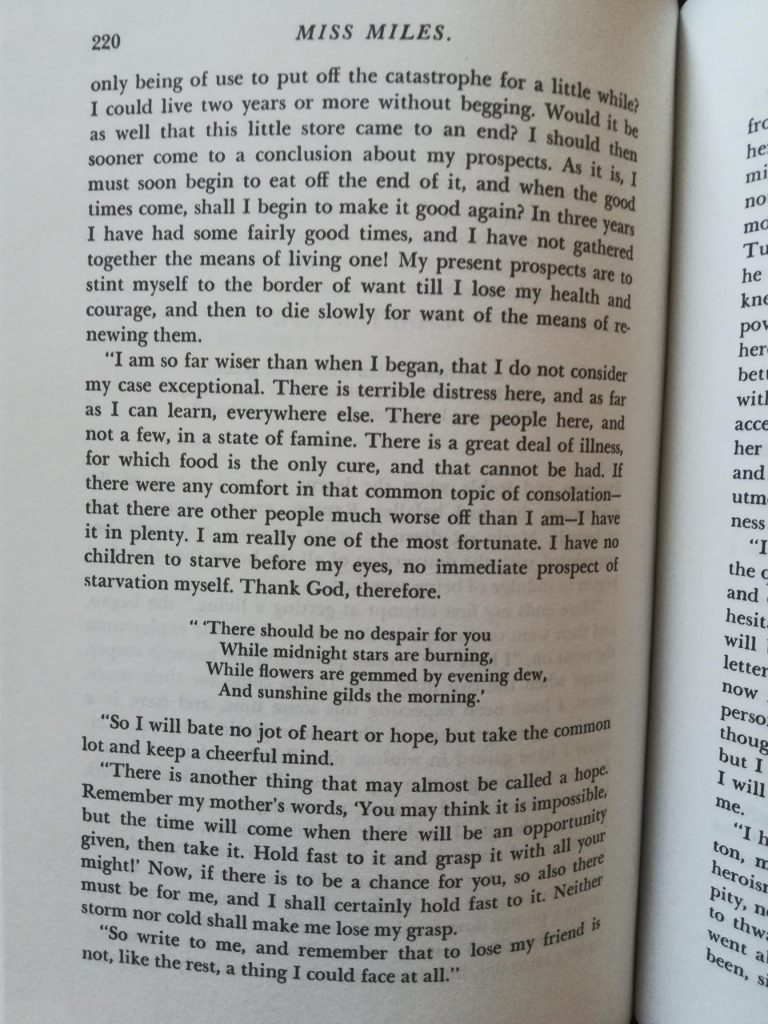

It is clear that Mary was very proud of Charlotte and her book, especially as her own dream of being a writer was not proving fruitful. The 150 pages that Mary talks of having written were probably from an early draft of her own novel Miss Miles, which was not published until 42 years after Mary wrote this letter.

Mary Taylor did however become a relatively successful writer of articles for magazines, of which some are seen as early examples of feminist journalism. It’s interesting to note however that despite Mary’s admonishment of Charlotte for not preaching a doctrine, her own Miss Miles is itself free of obvious preaching.

What do we make of Mary’s opinion of St. John Rivers? Not many people reading the book today would think that Charlotte had sugar coated him, or see him as a relentlessly ‘good’ character. We can, however, share Mary’s astonishment that a reader thought that Jane should have married the hectoring preacher.

We can also see that Charlotte has previously given Mary notice of her writing, and of her dealings with the publishers Smith, Elder & Co. We see that she has signed a contract to deliver two more novels after Jane Eyre; alas, two more novels were all that Charlotte did write after signing that contract.

Above all, this is a letter that a friend would write to someone who knows her very well; she has no need to fear that Charlotte will take offence at her comments. It is a letter full of love, although that love and kindness is hidden beneath a veneer that both Mary and Charlotte could coat their letters with.

The great thing about a great novel such as Jane Eyre is that we can all read it and form our own opinions, and all are as valid as the next. I hope to see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.