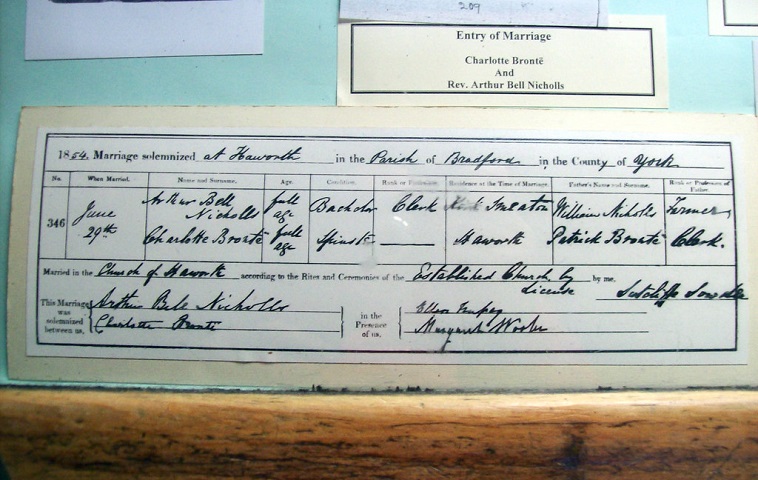

When happy anniversaries come along in the Brontë story, we simply have to celebrate them. This week marks the 167th anniversary of the marriage of Charlotte Brontë to Arthur Bell Nicholls, and their marriage was a happy (if brief, but we won’t dwell on that today) one.

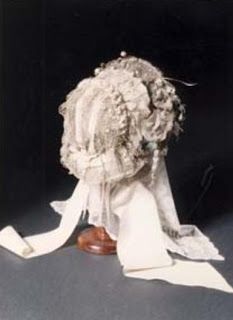

In previous years we’ve looked at events leading up to Charlotte Bronte’s wedding, and at an in-depth account of the big day itself given by one of the few people who were there: apprentice teacher James Robinson. The wedding was kept a secret from Haworth villagers, but we hear that those who saw Charlotte in her wedding dress said that she looked like a snowdrop.

In today’s post we’re going to keep the romantic theme going by looking at weddings in the Brontë novels. They don’t always go to plan, as we see from our first excerpt:

Jane Eyre I

‘I rose. There were no groomsmen, no bridesmaids, no relatives to wait for or marshal: none but Mr. Rochester and I. Mrs. Fairfax stood in the hall as we passed. I would fain have spoken to her, but my hand was held by a grasp of iron: I was hurried along by a stride I could hardly follow; and to look at Mr. Rochester’s face was to feel that not a second of delay would be tolerated for any purpose. I wonder what other bridegroom ever looked as he did – so bent up to a purpose, so grimly resolute: or who, under such steadfast brows, ever revealed such flaming and flashing eyes.

I know not whether the day was fair or foul; in descending the drive, I gazed neither on sky nor earth: my heart was with my eyes; and both seemed migrated into Mr. Rochester’s frame. I wanted to see the invisible thing on which, as we went along, he appeared to fasten a glance fierce and fell. I wanted to feel the thoughts whose force he seemed breasting and resisting.

At the churchyard wicket he stopped: he discovered I was quite out of breath. “Am I cruel in my love?” he said. “Delay an instant: lean on me, Jane.”

And now I can recall the picture of the grey old house of God rising calm before me, of a rook wheeling round the steeple, of a ruddy morning sky beyond. I remember something, too, of the green grave-mounds; and I have not forgotten, either, two figures of strangers straying amongst the low hillocks and reading the mementoes graven on the few mossy head-stones. I noticed them, because, as they saw us, they passed round to the back of the church; and I doubted not they were going to enter by the side-aisle door and witness the ceremony. By Mr. Rochester they were not observed; he was earnestly looking at my face, from which the blood had, I daresay, momentarily fled: for I felt my forehead dewy, and my cheeks and lips cold. When I rallied, which I soon did, he walked gently with me up the path to the porch.

We entered the quiet and humble temple; the priest waited in his white surplice at the lowly altar, the clerk beside him. All was still: two shadows only moved in a remote corner. My conjecture had been correct: the strangers had slipped in before us, and they now stood by the vault of the Rochesters, their backs towards us, viewing through the rails the old time-stained marble tomb, where a kneeling angel guarded the remains of Damer de Rochester, slain at Marston Moor in the time of the civil wars, and of Elizabeth, his wife.

Our place was taken at the communion rails. Hearing a cautious step behind me, I glanced over my shoulder: one of the strangers – a gentleman, evidently – was advancing up the chancel. The service began. The explanation of the intent of matrimony was gone through; and then the clergyman came a step further forward, and, bending slightly towards Mr. Rochester, went on.

“I require and charge you both (as ye will answer at the dreadful day of judgment, when the secrets of all hearts shall be disclosed), that if either of you know any impediment why ye may not lawfully be joined together in matrimony, ye do now confess it; for be ye well assured that so many as are coupled together otherwise than God’s Word doth allow, are not joined together by God, neither is their matrimony lawful.”

He paused, as the custom is. When is the pause after that sentence ever broken by reply? Not, perhaps, once in a hundred years. And the clergyman, who had not lifted his eyes from his book, and had held his breath but for a moment, was proceeding: his hand was already stretched towards Mr. Rochester, as his lips unclosed to ask, “Wilt thou have this woman for thy wedded wife?” – when a distinct and near voice said –

“The marriage cannot go on: I declare the existence of an impediment.”

The clergyman looked up at the speaker and stood mute; the clerk did the same; Mr. Rochester moved slightly, as if an earthquake had rolled under his feet: taking a firmer footing, and not turning his head or eyes, he said, “Proceed.”

Profound silence fell when he had uttered that word, with deep but low intonation. Presently Mr. Wood said –

“I cannot proceed without some investigation into what has been asserted, and evidence of its truth or falsehood.”

“The ceremony is quite broken off,” subjoined the voice behind us. “I am in a condition to prove my allegation: an insuperable impediment to this marriage exists.”

Mr. Rochester heard, but heeded not: he stood stubborn and rigid, making no movement but to possess himself of my hand. What a hot and strong grasp he had! and how like quarried marble was his pale, firm, massive front at this moment! How his eye shone, still watchful, and yet wild beneath!

Mr. Wood seemed at a loss. “What is the nature of the impediment?” he asked. “Perhaps it may be got over – explained away?”

“Hardly,” was the answer. “I have called it insuperable, and I speak advisedly.”

The speaker came forward and leaned on the rails. He continued, uttering each word distinctly, calmly, steadily, but not loudly –

“It simply consists in the existence of a previous marriage. Mr. Rochester has a wife now living.”

Jane Eyre II

‘Reader, I married him. A quiet wedding we had: he and I, the parson and clerk, were alone present. When we got back from church, I went into the kitchen of the manor-house, where Mary was cooking the dinner and John cleaning the knives, and I said –

“Mary, I have been married to Mr. Rochester this morning.” The housekeeper and her husband were both of that decent phlegmatic order of people, to whom one may at any time safely communicate a remarkable piece of news without incurring the danger of having one’s ears pierced by some shrill ejaculation, and subsequently stunned by a torrent of wordy wonderment. Mary did look up, and she did stare at me: the ladle with which she was basting a pair of chickens roasting at the fire, did for some three minutes hang suspended in air; and for the same space of time John’s knives also had rest from the polishing process: but Mary, bending again over the roast, said only –

“Have you, Miss? Well, for sure!”

A short time after she pursued – “I seed you go out with the master, but I didn’t know you were gone to church to be wed;” and she basted away. John, when I turned to him, was grinning from ear to ear.

“I telled Mary how it would be,” he said: “I knew what Mr. Edward” (John was an old servant, and had known his master when he was the cadet of the house, therefore, he often gave him his Christian name) – “I knew what Mr. Edward would do; and I was certain he would not wait long neither: and he’s done right, for aught I know. I wish you joy, Miss!” and he politely pulled his forelock.

“Thank you, John. Mr. Rochester told me to give you and Mary this.” I put into his hand a five-pound note. Without waiting to hear more, I left the kitchen. In passing the door of that sanctum some time after, I caught the words –

“She’ll happen do better for him nor ony o’ t’ grand ladies.” And again, “If she ben’t one o’ th’ handsomest, she’s noan faâl and varry good-natured; and i’ his een she’s fair beautiful, onybody may see that.”

Agnes Grey

‘Here I pause. My Diary, from which I have compiled these pages, goes but little further. I could go on for years, but I will content myself with adding, that I shall never forget that glorious summer evening, and always remember with delight that steep hill, and the edge of the precipice where we stood together, watching the splendid sunset mirrored in the restless world of waters at our feet – with hearts filled with gratitude to heaven, and happiness, and love – almost too full for speech.

A few weeks after that, when my mother had supplied herself with an assistant, I became the wife of Edward Weston; and never have found cause to repent it, and am certain that I never shall. We have had trials, and we know that we must have them again; but we bear them well together, and endeavour to fortify ourselves and each other against the final separation – that greatest of all afflictions to the survivor. But, if we keep in mind the glorious heaven beyond, where both may meet again, and sin and sorrow are unknown, surely that too may be borne; and, meantime, we endeavour to live to the glory of Him who has scattered so many blessings in our path.

Edward, by his strenuous exertions, has worked surprising reforms in his parish, and is esteemed and loved by its inhabitants – as he deserves; for whatever his faults may be as a man (and no one is entirely without), I defy anybody to blame him as a pastor, a husband, or a father.

Our children, Edward, Agnes, and little Mary, promise well; their education, for the time being, is chiefly committed to me; and they shall want no good thing that a mother’s care can give. Our modest income is amply sufficient for our requirements: and by practising the economy we learnt in harder times, and never attempting to imitate our richer neighbours, we manage not only to enjoy comfort and contentment ourselves, but to have every year something to lay by for our children, and something to give to those who need it.

And now I think I have said sufficient.’

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

‘To return, however, to my own affairs: I was married in summer, on a glorious August morning. It took the whole eight months, and all Helen’s kindness and goodness to boot, to overcome my mother’s prejudices against my bride-elect, and to reconcile her to the idea of my leaving Linden Grange and living so far away. Yet she was gratified at her son’s good fortune after all, and proudly attributed it all to his own superior merits and endowments. I bequeathed the farm to Fergus, with better hopes of its prosperity than I should have had a year ago under similar circumstances; for he had lately fallen in love with the Vicar of L – – ’s eldest daughter – a lady whose superiority had roused his latent virtues, and stimulated him to the most surprising exertions, not only to gain her affection and esteem, and to obtain a fortune sufficient to aspire to her hand, but to render himself worthy of her, in his own eyes, as well as in those of her parents; and in the end he was successful, as you already know. As for myself, I need not tell you how happily my Helen and I have lived together, and how blessed we still are in each other’s society, and in the promising young scions that are growing up about us. We are just now looking forward to the advent of you and Rose, for the time of your annual visit draws nigh, when you must leave your dusty, smoky, noisy, toiling, striving city for a season of invigorating relaxation and social retirement with us.’

Shirley

‘It is August. The bells clash out again, not only through Yorkshire, but through England. From Spain the voice of a trumpet has sounded long; it now waxes louder and louder; it proclaims Salamanca won. This night is Briarfield to be illuminated. On this day the Fieldhead tenantry dine together; the Hollow’s Mill workpeople will be assembled for a like festal purpose; the schools have a grand treat. This morning there were two marriages solemnized in Briarfield church – Louis Gérard Moore, Esq., late of Antwerp, to Shirley, daughter of the late Charles Cave Keeldar, Esq., of Fieldhead; Robert Gérard Moore, Esq., of Hollow’s Mill, to Caroline, niece of the Rev. Matthewson Helstone, M.A., rector of Briarfield.

The ceremony, in the first instance, was performed by Mr. Helstone, Hiram Yorke, Esq., of Briarmains, giving the bride away. In the second instance, Mr. Hall, vicar of Nunnely, officiated. Amongst the bridal train the two most noticeable personages were the youthful bridesmen, Henry Sympson and Martin Yorke.

I suppose Robert Moore’s prophecies were, partially at least, fulfilled. The other day I passed up the Hollow, which tradition says was once green, and lone, and wild; and there I saw the manufacturer’s day-dreams embodied in substantial stone and brick and ashes – the cinder-black highway, the cottages, and the cottage gardens; there I saw a mighty mill, and a chimney ambitious as the tower of Babel. I told my old housekeeper when I came home where I had been.

“Ay,” said she, “this world has queer changes. I can remember the old mill being built – the very first it was in all the district; and then I can remember it being pulled down, and going with my lake-lasses [companions] to see the foundation-stone of the new one laid. The two Mr. Moores made a great stir about it. They were there, and a deal of fine folk besides, and both their ladies; very bonny and grand they looked. But Mrs. Louis was the grandest; she always wore such handsome dresses. Mrs. Robert was quieter like. Mrs. Louis smiled when she talked. She had a real, happy, glad, good-natured look; but she had een that pierced a body through. There is no such ladies nowadays.”

What was the Hollow like then, Martha?”

“Different to what it is now; but I can tell of it clean different again, when there was neither mill, nor cot, nor hall, except Fieldhead, within two miles of it. I can tell, one summer evening, fifty years syne, my mother coming running in just at the edge of dark, almost fleyed out of her wits, saying she had seen a fairish in Fieldhead Hollow; and that was the last fairish that ever was seen on this countryside (though they’ve been heard within these forty years). A lonesome spot it was, and a bonny spot, full of oak trees and nut trees. It is altered now.”

The story is told. I think I now see the judicious reader putting on his spectacles to look for the moral. It would be an insult to his sagacity to offer directions. I only say, God speed him in the quest!’

The world has changed greatly since the time of the Brontës, but you still can’t beat a good wedding! On an unrelated note, I hope that many of you got the chance to see the new documentary ‘Brontë’s Britain with Gyles Brandreth on Channel 5’ on Tuesday. I was lucky enough to appear in it myself, and I loved filming it and watching the finished show. If you live in the UK you can watch it at the following link, and hopefully it should be available in other countries soon: https://www.my5.tv/bronte-s-britain-with-gyles-brandreth/season-1/bronte-s-britain-with-gyles-brandreth

I hope to see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.

I’m looking forward to watching ‘Bronte’s Britain’.

Another fine TV documentary, made in 2013 and available in full on YouTube, is ‘The Brilliant Bronte Sisters’ hosted by Sheila Hancock: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLI1Bm6rNuc

Sheila makes a point of championing Anne as the equal of her sisters, a protofeminist, highlighting in ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ the unfairness of the marriage laws towards women and giving an accurate and powerful portrayal of alcoholism.

Thank you very much for sharing that link Maria – a fabulous documentary!

Thank you. And with pictures too!

Hi Nick

Interesting article. Did Charlotte’s husband Arthur remarry after her death?

I am currently reading your biography of Anne and am wondering if there are any books available on disease and the Brontes, i. e. A diagnosis of their ailments, Charlotte’s migraines, Maria’s fatal illness, etc.

Thanks

Thanks Mel! Yes, after returning to Ireland Arthur married his cousin Mary Bell and they ran a farm together. It may have been a marriage of convenience, as Arthur had been raised by his uncle, Mary’s father, and so they were brought up like brother and sister. Certainly it seems that Charlotte remained the love of his life.

There isn’t a book as such, but there is a really good 9 page essay on the subject, ‘A Medical Appraisal Of The Brontes’ by Professor Philip Rhodes. Published in 1972 you can read it online if you have a Bronte Studies subscription, and it’s a chapter in an excellent book called ‘Classics of Bronte Scholarship’.

As always a really interesting enjoyable post. Loved the Gyles Brandreth show, you are a TV naturel, congratulations !

Thanks Debs! I may be back on the screen again before too long, but that’s all I can say for now!

How lovely to read thi!