On this day in 1848 two tired yet happy sisters boarded a steam train at Euston Station (that’s it at the head of this post) en route to Leeds, Keighley and finally Haworth. They were Charlotte and Anne Brontë, and they had just completed a four day sojourn in London which changed literary history forever.

Charlotte and Anne had travelled hastily to London in an attempt to clear their name from a scam being perpetuated by Anne’s ever unscrupulous publisher Thomas Cautley Newby. In previous posts we’ve looked at the Brontës’ time in London, but we haven’t heard from somebody who can explain it from a unique viewpoint: Charlotte Brontë herself. In today’s post I reproduce in full a letter sent by Charlotte to her friend Mary Taylor (at that time living in New Zealand); written two months after the London journey, it nevertheless gives a fulsome account of the days the Brontës spent there. I’ve also added some notes after the letter which here follows:

To Mary Taylor

Haworth, September 4th, 1848.

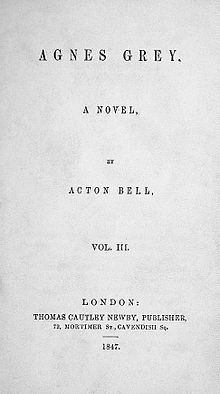

‘Dear Polly1, I write you a great many more letters than you write me, though whether they all reach you, or not, Heaven knows! I dare say you will not be without a certain desire to know how our affairs get on; I will give you therefore a notion as briefly as may be. Acton Bell has published another book; it is in three volumes, but I do not like it quite so well as Agnes Grey the subject not being such as the author had pleasure in handling; it has been praised by some reviews and blamed by others. As yet, only 25 have been realised for the copyright, and as Acton Bell’s publisher is a shuffling scamp, I expected no more.

About two months since I had a letter from my publishers Smith and Elder saying that Jane Eyre had had a great run in America, and that a publisher there had consequently bid high for the first sheets of a new work by Currer Bell, which they had promised to let him have.

Presently after came another missive from Smith and Elder; their American correspondent had written to them complaining that the first sheets of a new work by Currer Bell had been already received, and not by their house, but by a rival publisher, and asking the meaning of such false play; it enclosed an extract from a letter from Mr. Newby (A. and C. Bell’s publisher) affirming that to the best of his belief Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (the new work) were all the production of one author.

This was a lie, as Newby had been told repeatedly that they were the production of three different authors, but the fact was he wanted to make a dishonest move in the game to make the public and the trade believe that he had got hold of Currer Bell, and thus cheat Smith and Elder by securing the American publisher’s bid.

The upshot of it was that on the very day I received Smith and Elder’s letter, Anne and I packed up a small box, sent it down to Keighley, set out ourselves after tea, walked through a snow-storm to the station2, got to Leeds, and whirled up by the night train to London with the view of proving our separate identity to Smith and Elder, and confronting Newby with his lie.

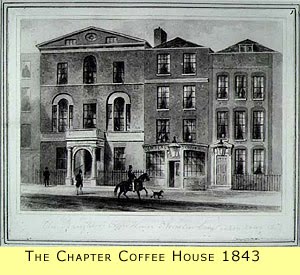

We arrived at the Chapter Coffee House (our old place, Polly, we did not well know where else to go) about eight o’clock in the morning3. We washed ourselves, had some breakfast, sat a few minutes, and then set off in queer inward excitement to 65 Cornhill. Neither Mr. Smith nor Mr. Williams knew we were corning, they had never seen us they did not know whether we were men or women, but had always written to us as men.

We found 65 to be a large bookseller’s shop, in a street almost as bustling as the Strand. We went in, walked up to the counter. There were a great many young men and lads here and there; I said to the first I could accost : ‘May I see Mr. Smith?’ He hesitated, looked a little surprised. We sat down and waited a while, looking at some books on the counter, publications of theirs well known to us, of many of which they had sent us copies as presents. At last we were shown up to Mr. Smith. ‘Is it Mr. Smith?’ I said, looking up through my spectacles at a tall young man. ‘It is.’ I then put his own letter into his hand directed to Currer Bell. He looked at it and then at me again. ‘Where did you get this?’ he said. I laughed at his perplexity a recognition took place. I gave my real name: Miss Brontë. We were in a small room ceiled with a great skylight and there explanations were rapidly gone into; Mr. Newby being anathematised, I fear, with undue vehemence. Mr. Smith hurried out and returned quickly with one whom he introduced as Mr. Williams, a pale, mild, stooping man of fifty, very much like a faded Tom Dixon4. Another recognition and a long, nervous shaking of hands. Then followed talk talk talk; Mr. Williams being silent, Mr. Smith loquacious.

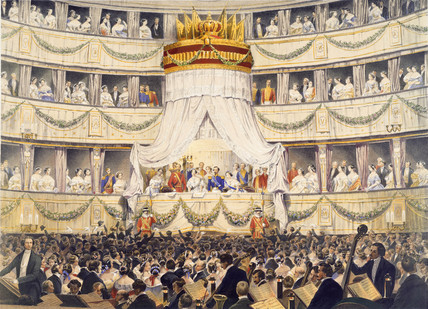

Mr. Smith said we must come and stay at his house, but we were not prepared for a long stay and declined this also; as we took our leave he told us he should bring his sisters to call on us that evening. We returned to our inn, and I paid for the excitement of the interview by a thundering headache and harassing sickness. Towards evening, as I got no better and expected the Smiths to call, I took a strong dose of sal volatile5. It roused me a little; still, I was in grievous bodily case when they were announced. They came in, two elegant young ladies, in full dress, prepared for the Opera Mr. Smith himself in evening costume, white gloves, etc. We had by no means understood that it was settled we were to go to the Opera, and were not ready. Moreover, we had no fine, elegant dresses with us, or in the world. However, on brief rumination I thought it would be wise to make no objections. I put my headache in my pocket, we attired ourselves in the plain, high-made country garments we possessed, and went with them to their carriage, where we found Mr. Williams. They must have thought us queer, quizzical-looking beings, especially me with my spectacles. I smiled inwardly at the contrast, which must have been apparent, between me and Mr. Smith as I walked with him up the crimson-carpeted staircase of the Opera House and stood amongst a brilliant throng at the box door, which was not yet open. Fine ladies and gentlemen glanced at us with a slight, graceful superciliousness quite warranted by the circumstances. Still, I felt pleasantly excited in spite of headache and sickness and conscious clownishness, and I saw Anne was calm and gentle, which she always is.

The performance was Rossini’s opera of the Barber of Seville, very brilliant, though I fancy there are things I should like better. We got home after one o’clock; we had never been in bed the night before, and had been in constant excitement for twenty-four hours. You may imagine we were tired.

The next day, Sunday, Mr. Williams came early and took us to church6. He was so quiet, but so sincere in his attentions, one could not but have a most friendly leaning towards him. He has a nervous hesitation in speech, and a difficulty in finding appropriate language in which to express himself, which throws him into the background in conversation; but I had been his correspondent and therefore knew with what intelligence he could write, so that I was not in danger of undervaluing him. In the afternoon Mr. Smith came in his carriage with his mother, to take us to his house to dine. Mr. Smith’s residence is at Bayswater, six miles from Cornhill; the rooms, the drawing-room especially, looked splendid to us. There was no company only his mother, his two grown-up sisters, and his brother, a lad of twelve or thirteen, and a little sister, the youngest of the family, very like himself. They are all dark-eyed, dark-haired, and have clear, pale faces. The mother is a portly, handsome woman of her age, and all the children more or less well-looking one of the daughters decidedly pretty. We had a fine dinner, which neither Anne nor I had appetite to eat, and were glad when it was over. I always feel under an awkward constraint at table. Dining out would be hideous to me.

Mr. Smith made himself very pleasant. He is a practical man, I wish Mr. Williams were more so, but he is altogether of the contemplative, theorising order. Mr. Williams has too many abstractions.

On Monday we went to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy and the National Gallery, dined again at Mr. Smith’s, then went home with Mr. Williams to tea and saw his comparatively humble but neat residence and his fine family of eight children. A daughter of Leigh Hunt’s was there7. She sang some little Italian airs which she had picked up among the peasantry in Tuscany, in a manner that charmed me.

On Tuesday morning we left London laden with books which Mr. Smith had given us, and got safely home, A more jaded wretch than I looked when I returned it would be difficult to conceive. I was thin when I went, but was meagre indeed when I returned; my face looked grey and very old, with strange, deep lines ploughed in it; my eyes stared unnaturally. I was weak and yet restless. In a while, however, the bad effects of excitement went off and I regained my normal condition. We saw Mr. Newby, but of him more another time8. Good-bye. God bless you. Write. C B.’

Notes to Charlotte’s letter:

1. Polly was Charlotte’s nickname for Mary Taylor. It was also the name given to one of the central characters of Villette: Polly Home, later encountered in the novel as the grand Countess Paulina de Bassompierre. When we first meet Polly she is a pretty, precocious child. Charlotte first met Mary Taylor at school at Roe Head, Mirfield where Mary was described by headmistress Margaret Wooler as ‘too pretty to live’.

2. Charlotte and Anne set out on the evening of July 7th 1848; even amidst the wuthering moorlands of Haworth it would seem unlikely to have a snowstorm on that day.

3. The Chapter Coffee House was on Paternoster Row behind St. Paul’s Cathedral; it was where Charlotte, Emily and Patrick Brontë had stayed there in 1842 en route to Brussels, accompanied by Mary Taylor and her brother Joe.

4. Tom Dixon was the youngest son of Abraham Dixon, an inventor and entrepreneur originally from Leeds but who moved with his family to Brussels. Tom Dixon was a cousin of Mary Taylor, and Charlotte often met Tom and his brother George, who later became MP for Birmingham, in Brussels.

5. Smelling salts; the ornate smelling salts bottles of Elizabeth and Maria Branwell (aunt and mother to the Brontës) are in the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection. Maria’s salts bottle became the property of Anne, but it seems likely that Charlotte also had a bottle.

6. Although staying in the shadow of the mighty St. Paul’s, Anne requested that they be taken to St. Stephen Walbrook church in the nearby City of London. This beautiful church was noted at the time for its preacher Reverend George Croly, whose views on religious salvation chimed with those of Anne.

7. Leigh Hunt was a poet and publisher, most known today for having been a great friend of John Keats. In 1813 Hunt’s newspaper called Prince George (later George IV) ‘corpulent’; this led to Hunt being arrested and jailed for two years.

8. If only we had an account of Charlotte and Anne’s meeting with Thomas Newby! Surprisingly the meeting didn’t end with Anne transferring her rights from Newby to the altogether more honest George Smith, possibly because Emily Brontë wasn’t there to discuss the matter with.

A charming and revealing letter, as so many of Charlotte’s are. Storm clouds were looming over Haworth when she and Anne returned, but these four days had been days of joy and happiness for them. I wish you all joy and happiness, and I hope to see you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.