I love reading Brontë novels and poems of course, but I also love reading about their lives. Modern biographers can’t follow in Elizabeth Gaskell’s footsteps by interviewing people who knew the Brontës but they can still find some fascinating first hand accounts hidden away in archives. The primary source for our information on the Brontës, however, is undoubtedly the letters of Charlotte Brontë. Things could have been very different if an instruction given by Arthur Bell Nicholls in October 1854 had been followed, so in today’s post we’re going to look at why.

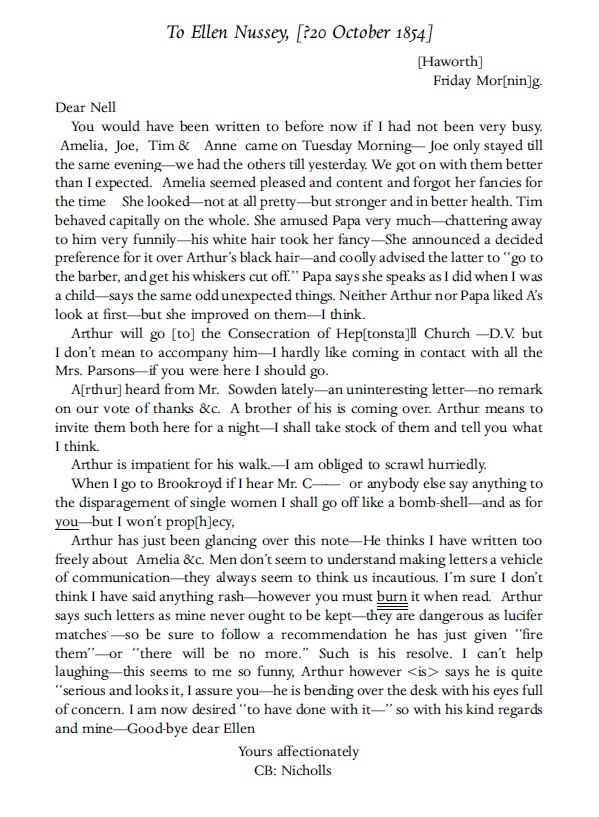

Charlotte’s main correspondent was her great friend Ellen Nussey. The letters to Ellen provide much of the information we know about the Brontës today, from details of their everyday lives to their writing endeavours and finally to accounts of the final days of Charlotte’s siblings. Charlotte was a frequent and brilliant letter writer, and each letter was written with a complete frankness and openness. It was this, it seems, that worried Arthur, by then Charlotte’s husband, as we see in this latter dated 20th October 1854:

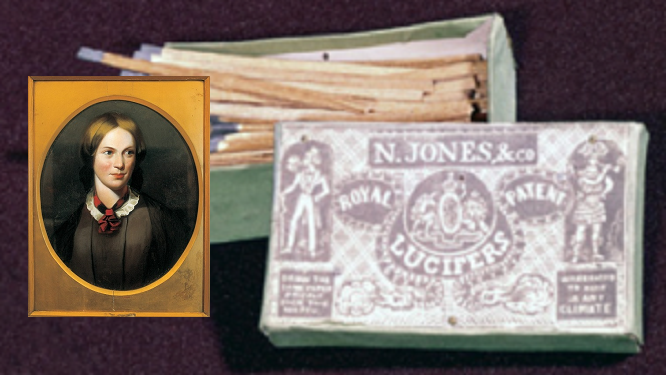

To Arthur, the frank nature of Charlotte’s letter made them as dangerous as lucifer matches – the white phosphorous headed matches which could be deadly not only to the match girls who made them but also because of the fires they could potentially cause. Perhaps Arthur was looking to the future? Convinced of his wife’s genius, he could see that her life story would one day be in demand, and that the letters she was writing now could potentially be read by others in the future.

Charlotte’s reaction was an interesting one in that she laughs off Arthur’s suggestion, saying that it is simply that men don’t understand the female art of letter writing. Nevertheless, she insists that Ellen sends a promise to burn her letters, if only to appease Arthur.

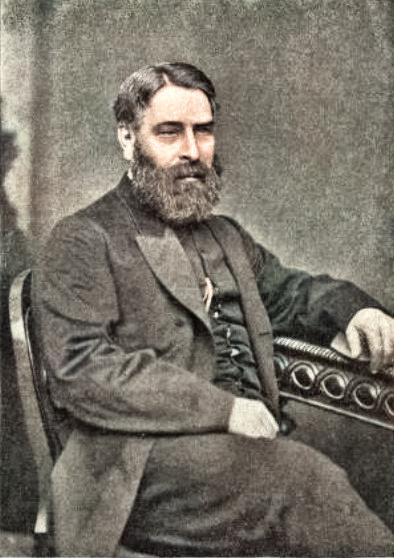

How did Ellen respond? Let’s take a look at a letter of two weeks later, dated on this day, 167 years ago, 7th November 1854:

At the start of the second paragraph, Charlotte writes, ‘Arthur thanks you for the promise’, before going on to explain that his purpose is not to prevent old friends from communicating freely but rather he is worried about them being seen by eyes they were not intended to be seen by.

So, Ellen has made a promise to burn Charlotte’s letters after reading, so what happened? It seems that Ellen herself was ashamed of the promise she had made. In fact, when Ellen gave a copy of this letter to Clement Shorter for use in a biography he was preparing, Ellen had deleted the start of the second paragraph and there is no mention of the promise at all.

The manuscript of this letter is now in the hands of the Brontë Parsonage Museum, and it tells a very interesting story as Ellen has written a running commentary, in pencil, alongside it. Her commentary reads ‘promise’, ‘conditional’, and ‘not complied with’, and at the foot of the letter Ellen has written, ‘he never did give the pledge.’

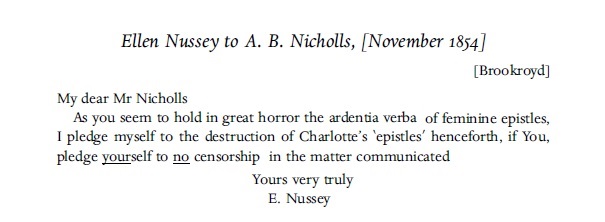

We also have the note that Ellen supplied to Arthur; it’s now in the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, and is in fact the only correspondence we have from Ellen to either Charlotte or Arthur (although there are many other letters from her extant). Here is a transcript of Ellen’s note:

Once again, however, Ellen’s pencil has later been used to interesting effect, as she has added the words: ‘Mr N continued his censorship so the pledge was void.’

The censorship talked of here indicates that Arthur had censored some of Charlotte’s letters before sending them on to Ellen. This practice seems abhorrent today, quite rightly, but it would have been nothing out of the ordinary at that time.

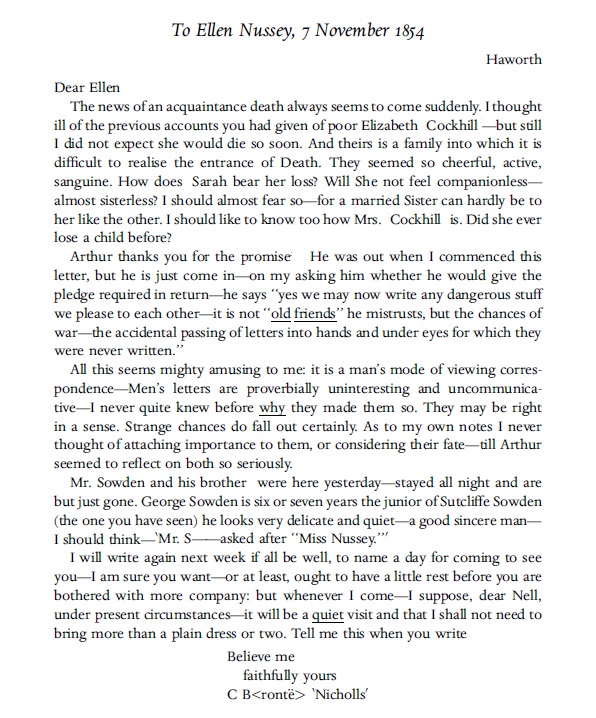

At the heart of the dispute over Charlotte’s letters was a great dislike between two of the most important people in Charlotte Brontë’s life: Arthur Bell Nicholls and Ellen Nussey, her husband and her best friend. In my view both of these people were kind and honest and both loved Charlotte deeply, but to say they didn’t get on is an understatement. Each believed the other to be monopolising Charlotte’s love, and Ellen’s bitterness at having to share Charlotte can be seen after the announcement of her engagement to Arthur; so angry was Ellen that she broke off all communication with Charlotte, and this estrangement stretched from July 1853 to February 1854. It was Margaret Wooler, who had once been headmistress to them both, who eventually brought them together again – in time for Ellen to serve as Charlotte’s bridesmaid.

Charlotte’s untimely passing in 1855 did little to reconcile Arthur and Ellen, in fact Ellen unfairly blamed Arthur for her friend’s death. One of the final letters we have from Ellen was written to Clement Shorter in 1895, two years before her own passing and forty years after Charlotte’s but her enmity for Arthur was far from forgotten. She writes:

‘I am also sadly grieved that you will not give an hour for special information [i.e. will not visit Ellen] when you can go all the way to Ireland to see that selfish man [Arthur] who certainly shortened C.B.’s life, none of the sisters liked him, least of all Emily, who probably saw deeper into character than C. and A. She used to walk into the room for anything she wanted without casting a look on him… His poor wife left to his ignorant nursing when better aid was proposed. He evaded all her wishes for one weeks change ere her illness began when it was her purpose to make a will free of his influence. It was made in her dying moments on half a sheet of paper under his eye. Who could complain of the last if he had been other than he was.’

Ellen later goes on to say that Arthur was responsible for Charlotte’s death because he should have known that she was too small and frail to have children. In truth, of course, Charlotte died because of hyperemesis gravidurum, a condition neither she nor Arthur could have anticipated.

The enmity between these two important people in Charlotte’s life is sad, especially as they were both people who loved Charlotte dearly. On the other hand, it could have brought great benefits for the world of literature. Mary Taylor, Charlotte’s other great friend, destroyed most of the letters Charlotte had sent her: perhaps Arthur had given her the same instruction, but she had complied with it, or perhaps she was simply following the convention of the time after Charlotte’s death? Ellen, however, preserved Charlotte’s letters for posterity because of her dislike and distrust of Arthur Bell Nicholls. It is thanks to that that we have so many of Charlotte’s wonderful letters available to us today, and so much Brontë history at our fingertips.

I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post, but I must also bring to your notice a special event to mark 200 years of Anne Brontë being held at Cross Street Chapel, Manchester next Saturday the 13th of November, starting at 7.30. Filled with music and poetry it should be a special night in honour of a very special woman.

I leave you now with one of Charlotte’s earliest letters to Ellen Nussey. Typically frank, typically loving, typically humorous, it burns brighter than any lucifer match.

Ellen Nussey was right to be annoyed at Arthur Nicholls depriving her followers/admirers/friends of her correspondence to us all . Obviously, intimate ,sensitive correspondence between the Bronte family would not be included or expected by her admirers . A sad gap in our understanding / yearning of details of Charlottes life is forever missing .