I don’t mean to frighten anyone, but it’s just over a month until Christmas. The cold nights are definitely making themselves felt, and every television ad break seems to be accompanied by jingling bells. There’s one writer above all others who has become associated with Christmas, and he has been very much on my mind recently for reasons I will come to later: Charles Dickens. In today’s blog post, we’re going to look at Dickens and the Brontës.

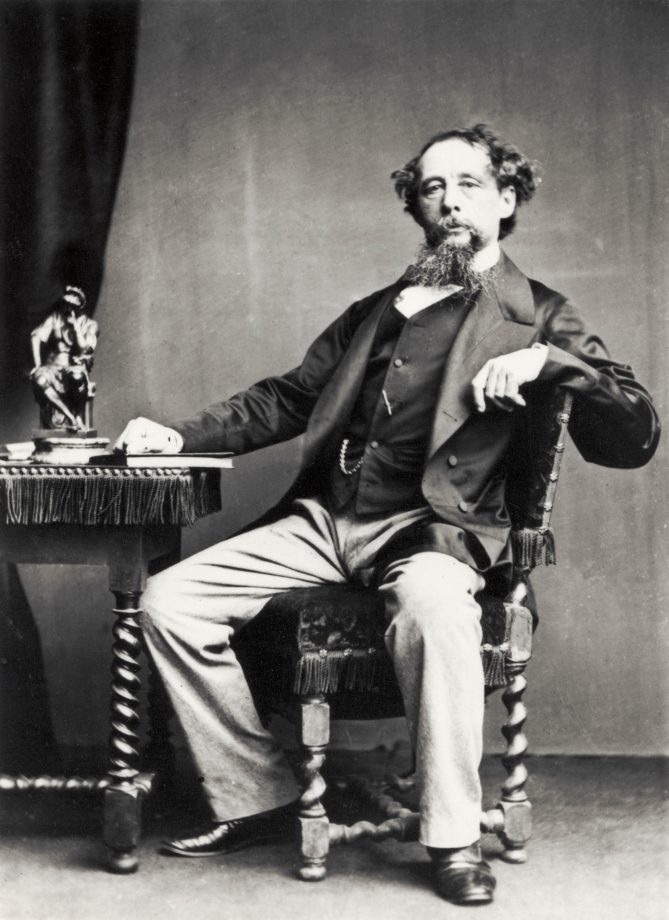

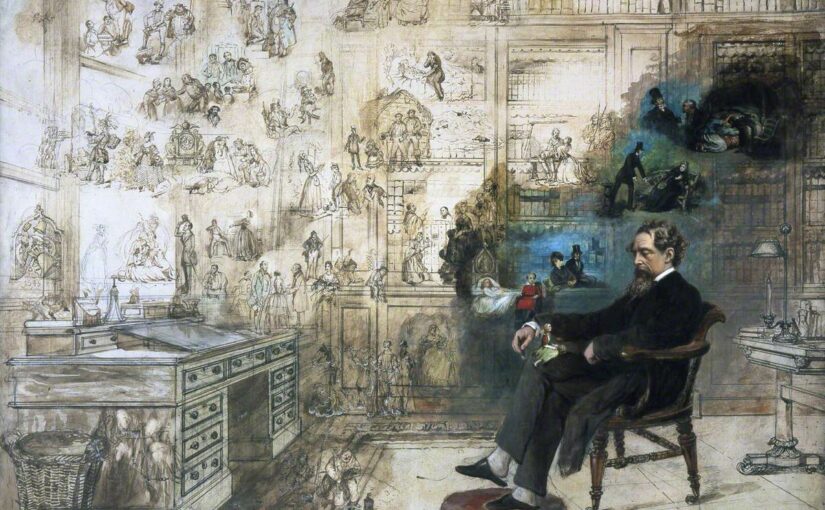

We can’t in the space of a single blog post give anything approximating to a precis of the life of Dickens. Charles John Huffam Dickens was born in Portsmouth in February 1812, making him four years older than Charlotte Brontë. His life could have descended into poverty in 1824 when his father was incarcerated in a debtor’s prison, and the 12 year old Charles had to leave school and begin work in a factory. It is perhaps this experience that gave Dickens his sympathy with the impoverished and downtrodden of 19th century society. Nevertheless, as we know, Dickens elevated himself greatly through the force of his talent and personality; he is today perhaps the most famous novelist of them all, and was one of the most celebrated men in Victorian England.

Dickens was connected to most of the great novelists of the century, many of whom he serialised and published in his hugely influential magazine ‘Household Words’. Today, however, let’s focus on one particular writer who is always of interest to us. I mentioned Dickens and the Brontës earlier, but it is Charlotte Brontë to whom we turn, for it was she who has left her opinion on his works.

In May 1849, she wrote to W. S. Williams to explain that she could never write a serialised novel of the kind that Dickens had made so popular:

‘I verily believe that the “nobler sex” find it more difficult to wait, to plod, to work out their destiny inch by inch, than their sisters do. They are always for walking so fast and taking such long steps, one cannot keep up with them. One should never tell a gentleman that one has commenced a task till it is nearly achieved. Currer Bell, even if he had no let or hindrance, and if his path was quite smooth, could never march with the tread of a Scott, a Bulwer, a Thackeray, or a Dickens. I want you and Mr. Smith clearly to understand this.’

In her letters Charlotte proclaimed herself particularly impressed by David Copperfield, but she took issue with one particular character in Bleak House:

‘Is the 1st. no. of Bleak House generally admired? I liked the Chancery part – but where it passes into the autobiographic form and the young woman who announces she is not “bright” begins her history – it seems to me too often weak and twaddling – an amiable nature is caricatured – not faithfully rendered in Miss Esther Summerson.’

So, we have seen that Charlotte Brontë held the work of Charles Dickens in some esteem but was critical of some aspects of it, but what did she think of the man? Did their paths ever cross? For an answer to that we turn to an obscure edition of an obscure magazine. ‘The Free Lance’ of 14th March 1868 contained an article by the author John Stores Smith. It is entitled ‘Personal Reminiscences: A Day With Charlotte Brontë’, so of course it’s of great interest to us.

Stores Smith explains in great, almost Dickensian, detail how he came to travel to Haworth one day in 1850 with the intention of meeting Charlotte Brontë. Haworth failed to impress him: ‘By the time I reached the end of its steep hill, my body was wearied, and my high spirits had all given way to an oppressive numbness of the soul. How anyone could live a life-time there, and not grow morbid, was incomprehensible.’ Neither was he taken by the parsonage: ‘The parsonage was a low stone house, which occupied one corner of the grave yard. A field had evidently been set apart, and the founders of the church had said: “In three-fourths of it we will inter the dead, and in that other fourth we will bury the living”… The stone of the house was of the same melancholy tint as the flags of the walk; a small door was in the centre, and a window on either side; in the only storey above were three windows, I think. Of all the sad, heart-broken looking dwellings I had passed throught this looked the saddest. A great sinking of spirit came over me, and I wished I had not come.’

Nevertheless, safely inside, Stores Smith was impressed by Charlotte Brontë, or at least by the hypnotic power of her eyes (something that just about everyone who ever met Charlotte commented on): ‘She was diminutive in height, and extremely fragile in figure. Her hand was one of the smallest I have ever grasped. She had no pretensions to being considered beautiful, and was as far removed from being plain. She had rather light brown hair, somewhat thin, and drawn plainly over her brow. Her complexion had no trace of colour in it, and her lips were pallid also; but she had a most sweet smile, with a touch of tender melancholy in it. Altogether she was as unpretending, undemonstrative, quiet a little lady as you could well meet. Her age I took to be about five-and-thirty. But when you saw and felt her eyes, the spirit that created Jane Eyre was revealed at once to you. They were rather small, but of a very peculiar colour, and had a strange lustre and intensity. They were chameleon-like, a blending of various brown and olive tints. But they looked you through and through – and you felt they were forming an opinion of you, not by mere acute noting of Lavaterish physiognomical peculiarities [Joahnn Kasper Lavater was the author of a groundbreaking book on physiognomy], but by a subtle penetration into the very marrow of your mind, and the innermost core of your sole. Taking my hand again she apologised for her enforced absence, and, as she did so, she looked right through me. There was no boldness in the gaze, but an intense, direct, searching look, as one who had the gift to read hidden mysteries, and the right to read them.’

A fascinating portrait of Charlotte Brontë, but it is a few simple lines later in the account that are particularly relevant to today’s post: ‘In 1850, shortly after her visit to London as a literary lioness, she pictured her impressions of metropolitan literary life in most forbidding colours, and with clear, cutting, intense distaste of it; I may even say contempt. Dickens she had met, and admired his genius, but did not like him. Her homely thrift, and unpretending, retiring nature, shrunk from him, from an idea she had acquired of ostentatious extravagance on his part.’

This is the only account of Charlotte Brontë and Charles Dickens meeting. Some have cited the lack of corroborative evidence as proof that Stores Smith was wrong, but in my opinion it’s almost certain to be true. The account of both Charlotte Brontë’s reaction to literary London rings true with what we know of her character and tastes, and the account of Dickens’ extravagance fits perfectly with his character too. Charlotte was in London in the summer of 1850 and attended a number of literary parties thrown by her friend and publisher George Smith – Dickens was in London too at the time and was known for attending such parties, so it would seem unlikely that a chance for a meeting hadn’t presented itself. It could be that Charlotte had indeed mentioned meeting Dickens in letters of the time, but that these letters are now lost as so many sadly are. Finally, there would be no reason at all for Stores Smith to invent the meeting, and as we see from his description of Charlotte he was possessed of an excellent memory.

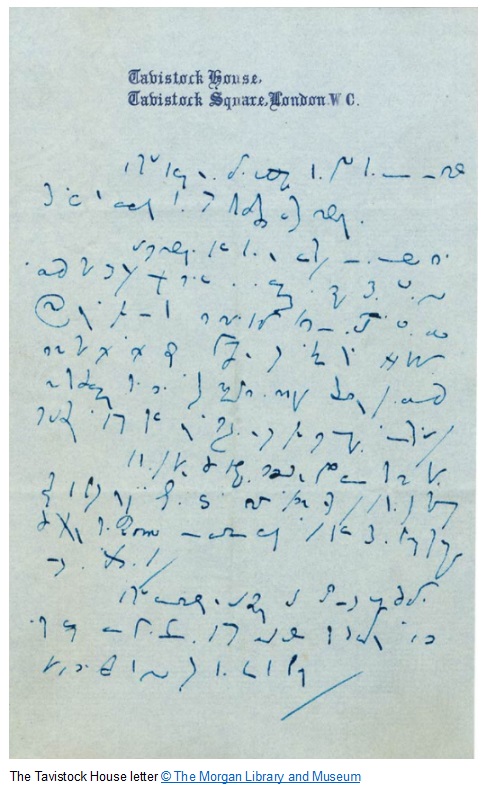

I’m confident in saying that Charlotte Brontë and Charles Dickens, these two enduring titans of Victorian literature, did meet. They were very different people, but they have both left a wonderful legacy for book lovers. Back to the start of my post: I said that Dickens had particularly caught my attention this week. That’s because a newly discovered letter on Tavistock House notepaper, presumed to be written by Dickens, has been placed before the world (Tavistock House was his London home from 1851 until 1860). The problem is that it is written in a code, in a type of shorthand that nobody has yet been able to decipher. The Dickens Project is offering £300 to anyone who can decode, or even partially decode it, but it has eluded my decoding skills so far. I reproduce the letter below, see if you can work out just what Charles Dickens was saying. I hope to see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.

I’m sure Charles could not have been far away when Charlotte invited to Thackery’s, good ole pal of Landseer. RA records show polymath Lanny was ‘distracted’ by ‘Oliver’ in 1837. The (greatest) artist collaborated with Dickens in subsequent ‘tales’. Landseer’s presence, and influence in Charlotte’s perceptions.. appear from 1830 (‘Hours of Innocence’ 3″ diagonal scar below right knee)- in 1837 Bran wrote his hero an ‘authoritive’ highbrow review; ‘On Landseer’s “Shepherds Chief Mourner” before the painting was exhibited (Bran actually describes a sister painting; ‘The Shepherd’s Grave’ which [as far as I know] was never exhibited.) Who did Patrick trust Bran to drive his sisters and precious Nussey, unarmed and unaccompanied, to greet them at Bolton Abbey summer ’33? ‘E’, the host was a pal of Jo Nussey (both sworn to 6th dk Dev’s ‘Bolton Bachelor’ decree along with George Howard and other social rebels; never marry under present, misogynist law), and now famous son of an old pal of the Parson. Landseer was in residence from c. 1st June ’till end of summer, and was the person with authority, knowledge and inclination who hosted and conducted the tour, leading to Charlotte’s regional fame and the family’s social watershed the following year (when they met key figures in their story). Can’t believe anything written while A.B-N alive. Wishing you well and hope your history continues to delve, and so will diverse. xjam

As usual, wonderful insights into the lives of the Brontes. So much has been lost to history, but thank God for historians who save every scrap … thank you for blogging and your obvious dedication to the Bronte family. I visited Haworth years ago and loved the charming little village, loved it. Also, while in London we visited Dicken’s Home … I so love the literary world of England and all those who have dedicated their lives in keeping the traditions. Living in California, it’s quite a distance, but will return! Again, thank you.

Living in California, it’s quite a distance but am determined to return one day.

Hi Nick – some of the characters look like Pitman Scipt shorthand I learnt 40 years ago. I still have the book upstairs so will go and see.

I do so enjoy your blog. Thank you for providing something to look forward to in Sundays.

This account of George M. Smith in Cornhill Magazine might be of interest:

(…)

“‘Villette ‘ is full of scenes which one can trace to incidents which occurred during Miss Bronte’s visits to us. (…) The scene of the fire comes from a slight accident to the scenery at Devonshire House, where Charles Dickens, Mr Forster, and other men of letters gave a perfomance. I took Charlotte Bronte and one of my sisters to Devonshire House (…) ”

(The Brontes – Interviews and Recollections, Macmillan Presss LTD, Page 101; initally published in Cornhill Magazine, Vo. IX (Dec. 1900) by George M. Smith