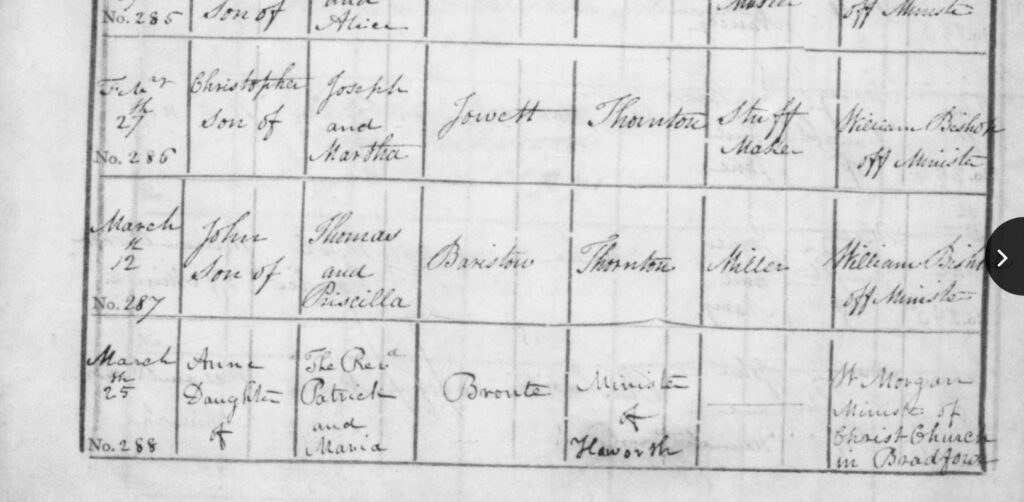

Last week we marked the birth of Anne Brontë, sixth and last of the Brontë siblings. Life must have been crowded in Thornton Parsonage at the beginning of 1820 but it wouldn’t remain like that for long, for just three months later the Brontë family were heading across the moors to a new parish and a new life in Haworth. Haworth is where Anne Brontë spent her infancy, and its those formative years which we’re going to look at in today’s post.

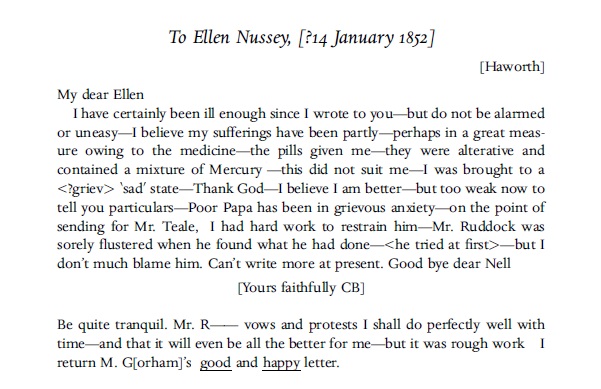

It’s a particularly appropriate time to looking at babies, as it was also on this day in 1855 that Charlotte Brontë was diagnosed as being pregnant by doctors Amos Ingham and William MacTurk. MacTurk, a leading Bradford doctor, had said that Charlotte’s symptoms were symptomatic – by which he meant symptomatic of pregnancy. He also said that Charlotte was ‘in no immediate danger’, but alas he was wrong. The tragic loss of Charlotte at the close of March shows how dangerous pregnancy was at the time for mother and baby alike; it must have been a cause for rejoicing in the Brontë household in 1820, therefore, when 36 year old Maria was delivered of her sixth child, all of whom had been born healthy.

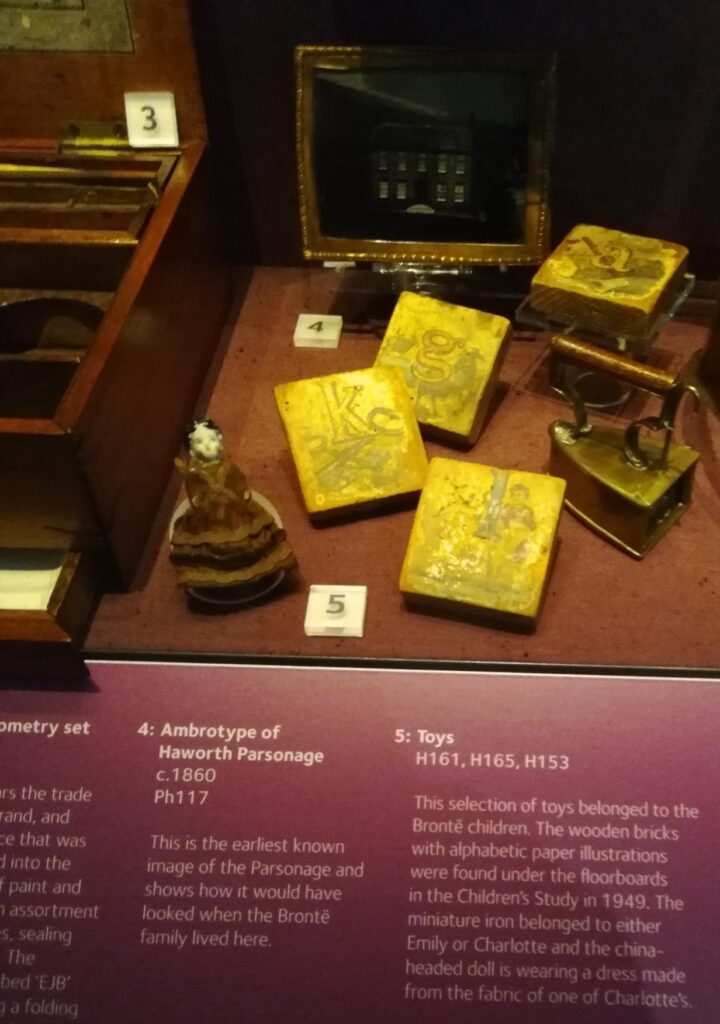

As the youngest Anne would surely have been doted upon, but in a family such as the Brontës where money was often scarce shed would also have been given hand-me-downs from her older sisters and brother. This would have included toys, and the Brontë Parsonage Museum has a collection of Brontë toys in their collection. They were discovered under the floorboards during renovations, presumably placed there by Patrick Brontë. What we have are alphabet building blocks, still a staple for children today, a tiny doll with a hand made dress and a porcelain head, and a miniature iron so that the girls could prepare for a future life wielding the real thing. All of these are likely to have ended their useful career in the hands of the infant Anne Brontë.

We know that Anne must have had a liking for dolls for in June 1826 Patrick Brontë returned from a trip to Leeds with a gift for his six year old daughter: a dancing doll, a doll made of card or strong paper with jointed legs and arms secured by pins allowing it to dance.

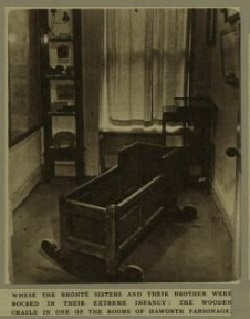

Another hand-me-down utilised for Anne would surely have been the cradle, and this image from 1955 shows this Brontë crib on display. Positioned on rockers it would have allowed Anne to be rocked gently from side to side, and it probably housed her siblings before her. It has been many years since this wonderful item was last on display; presumably it’s now in too fragile a state?

This is surely the cradle which features in the most famous story of Anne’s infancy. It was Nancy de Garrs, the servant who followed the family from Thornton to Haworth, who recalled the event: “When Anne was a baby, Charlotte rushed into her Papa’s study to say that there was an angel standing by Anne’s cradle, but when they returned it was gone, though Charlotte was sure she had seen it.”

This would have been shortly after the death of their mother, so the effect must have been dramatic upon Charlotte, but it’s perhaps also testimony to Anne’s angelic nature as a baby. A quiet child she became a quiet adult, albeit one who knew how to roar when she had to.

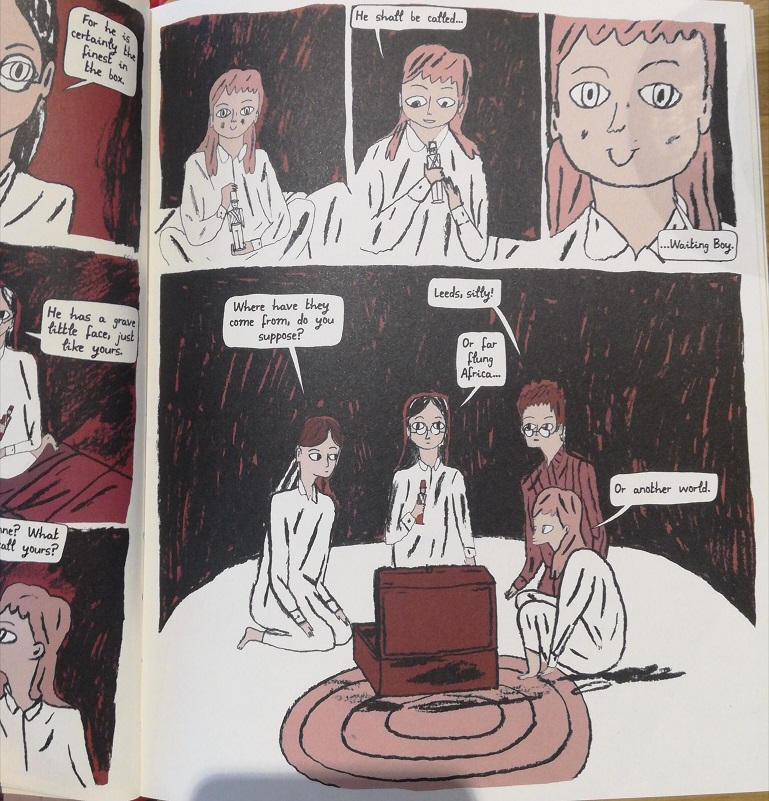

We get a hint of this reserved side of Anne’s nature, even during childhood, during another famous Brontë childhood scene. We saw how Patrick gifted Anne a dancing doll in the summer of 1826, and it was on this same journey that Patrick brought back another gift too – a dozen toy soldiers. The young Charlotte recounted what happened next:

“Papa bought Branwell some wooden soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night, and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed, and I snatched up one and exclaimed: ‘This is the Duke of Wellington! This shall be the Duke!’ when I had said this Emily likewise took one up and said it should be hers; when Anne came down, she said one should be hers. Mine was the prettiest of the whole, and the tallest, and the most perfect in every part. Emily’s was a grave-looking fellow, and we called him ‘Gravey’. Anne’s was a queer little thing, much like herself, and we called him ‘Waiting-boy’.”

Charlotte’s soldier was the prettiest and tallest of them all, which is perhaps wishful thinking given that she was self-conscious about her diminutive stature throughout her life. By this age, at just ten years old, Charlotte has had to take on the mantle of eldest sister and almost a mother to her siblings, so perhaps this is why she is dismissive of her six year old sister: Charlotte sees herself as a grown up far removed from the childhood things of Anne’s infancy. She perhaps sees Anne as the quiet one who is always waiting around but can’t yet fully join in with their games: a waiting girl.

So we see that patience and quiet reflection were characteristics of Anne from the earliest age, and they would remain her close companions throughout her life.

We could also speculate that it was Anne’s childhood charms that worked their magic on Elizabeth Branwell. Elizabeth came to Haworth from Penzance to nurse her dying sister, but after a suitable period of mourning had elapsed she could have returned. After all, she had previously visited Yorkshire in 1815, staying over a year in Thornton and taking in the christening of her god-daughter Elizabeth Brontë and the birth of Charlotte, but after that she took the 400 mile journey home to Cornwall again. What was different this time?

The attraction of Cornwall, with its warm climate and her well-to-do family near at hand, must have been great, but now the attraction of this windswept moorside parsonage was even greater. There lived six children who were the closest thing to her heart in the world; above all, there was the gentle baby Anne just one year old and in need of a mother; Elizabeth never saw Cornwall again, she stayed and became Aunt Branwell. From that moment and throughout her childhood, Anne shared a room in the parsonage with her aunt. It’s little surprise then that, as Ellen Nussey wrote, ‘Anne, dear, gentle Anne, was quite different in appearance from the others. She was her aunt’s favourite.’

In the infant and child Anne Brontë we can see the adult Anne Brontë, and by the time she put quill to paper on her two brilliant novels her waiting days were over. Thank you for sharing part of your Sunday with me, I hope you’re in good health and I hope to see you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.