Well, we’ve made it through a whole week of 2022. Have you noticed a difference yet? Charlotte Brontë certainly noticed a difference in the first week of 1844 for she began it in Belgium and ended it among her familiar Yorkshire moors. In today’s Brontë blog post we’re going to look at Charlotte Brontë’s return from Brussels, and what it meant for her writing.

Charlotte Brontë first arrived in Brussels in February 1842, alongside her sister Emily whilst Anne was sadly ensconced as a governess at Thorp Green Hall near York. They returned to Haworth in November of that year after the death of Aunt Branwell, unfortunately arriving too late for her funeral. Home loving Emily decided to remain in Haworth, but Charlotte insisted upon returning to Brussels. Ostensibly this was so she could continue honing her language skills prior to opening a school with her sisters, but in reality it had a lot to do with the fact that she had fallen in love with her French master Constantin Heger. Unfortunately, he was the husband of the school’s proprietor.

It was never going to end well, even though after her return from Haworth Charlotte was elevated to the position of teacher rather than simply being a pupil. By the end of 1843, the atmosphere in the Brussels Pensionnat (school) had become rather strained. An 1896 obituary for Constantin Heger, written by his friend Albert Colin, gave an insight into Madame Heger’s feelings by late 1843:

‘At the end of two years [after Charlotte Brontë’s 1842 entrance into the Pensionnat], the future English novelist spoke and wrote correctly the language of Bossuet, Racine and Voltaire. Once this had been achieved, Madame Heger, considering that her part of the contract morally entered into between herself and Charlotte had been completely fulfilled, refused to receive Miss Brontë a third year in her school. According to the statements of her own schoolfellows, the daughter of the English clergyman [sic] was anything but popular. She was also older than the other pupils, among whom she perhaps felt herself to be in a somewhat undignified position. Madame Heger was, therefore, not sorry to put an end to the connection.’

It seems therefore that Charlotte had requested to stay in Brussels, and presumably continue her work as a teacher, but had been refused. She was left with no choice but to return to England, and on 29th December 1843 her time at the Pensionnat was drawn to an official end with the presentation to her of a diploma certifying that she had completed her studies. The diploma is lost, but not the envelope it came in, for Charlotte herself has written on the outside: ‘Diploma given to me by Monsieur Heger Decbr 29th 1843.’ It had come from Constantin Heger, it must be treasured.

A sad new year indeed it must have seemed for Charlotte, for on the first of January 1844 she turned and took a final look at the Pensionnat, her eyes perhaps moving one last time to the window of the study of Monsieur Heger. As her carriage took her away from the city and towards the coast, did she know that this would be the last time she would ever see Brussels, or did she think she would be returning again one day when Madame Heger’s heart had softened?

After two days of travelling, on 3rd January 1844, Charlotte Brontë arrived back in Haworth to find that Anne and Branwell were preparing to leave for York, her best friend Ellen was staying with her brother Henry in Sussex, and her father was nearly blind. But she was home, and she was loved.

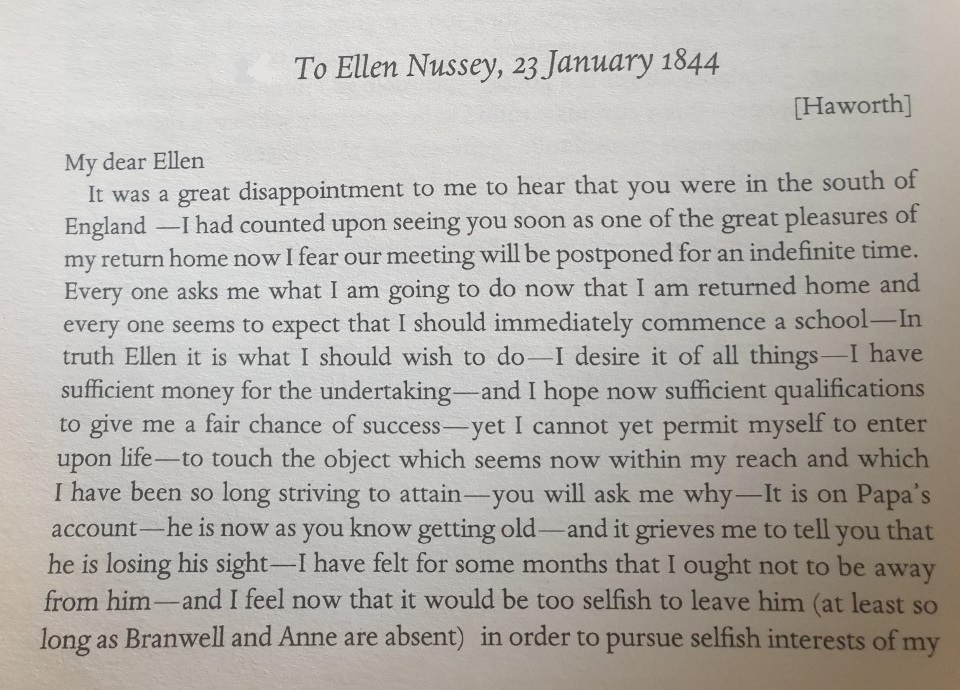

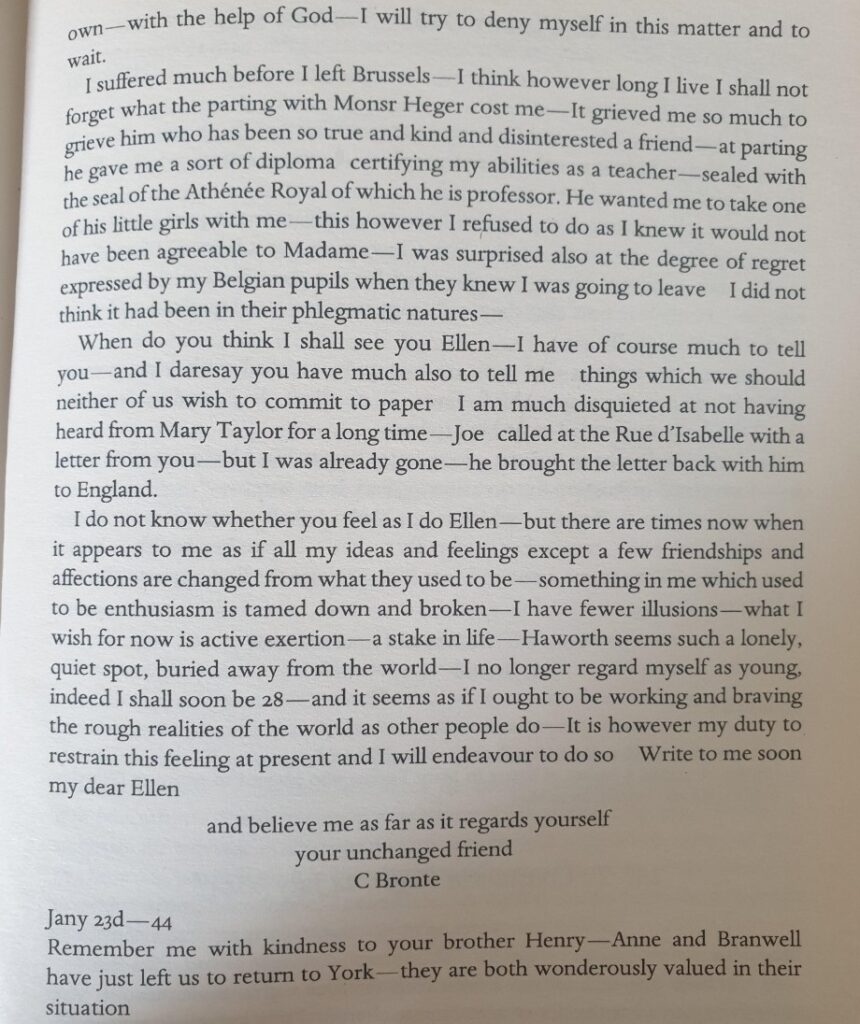

In the days that followed Charlotte must have realised that her European adventure was over, and she was left “tamed down and broken”. On 23rd January Charlotte finally raised the energy to write to Ellen, and a fascinating yet melancholic letter it is:

It’s also interesting to note that before leaving for Brussels in 1842 she had to persuade her Aunt Elizabeth to pay for the travel and tuition for herself and Emily, but now she has enough money to open her own school if she wanted to. The reason, of course, is that she (along with sisters Emily and Anne and cousin Eliza Kingston of Penzance) has now inherited a considerable sum of money from her Aunt’s will.

The school idea was now possible, but it would never open. The money would eventually be put to even greater use: it funded the publication of the first Brontë book, Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell and the entrance of the Brontës into the world of literature. Charlotte’s time in Brussels, and the manner of her return from it, also played a great role in those classic novels to come.

Charlotte had been in love with Constantin Heger, an unrequited love that seeped into her bones and played restlessly with her mind. There was no outlet in the despairing letters that she sent to Monsieur Heger as they went unacknowledged and unanswered; it must have another outlet.

In Charlotte’s letters sent from Brussels we see that Monsieur Heger was a stern man with a hard countenance, one who does not show emotions easily, and yet it was these qualities that won Charlotte’s esteem and then heart. In May 1842 she had written to Ellen:

‘There is one individual of whom I have not yet spoken: Monsieur Heger the husband of Madame. He is professor of Rhetoric, a man of power as to mind but very choleric and irritable in temperament – a little, black, ugly being with a face that varies in expression. Sometimes he borrows the lineaments of an insane Tom-cat – sometimes those of a delirious hyena – occasionally, but very seldom, he discards these perilous attractions and assumes an air not above a hundred degrees removed from what you would call mild and gentleman-like.’

Surely from this we see more than a hint of Edward Rochester? When Bessie asks Jane about her employer she replies:

‘She wanted to know if I was happy at Thornfield Hall, and what sort of a person the mistress was; and when I told her there was only a master, whether he was a nice gentleman, and if I liked him. I told her he was rather an ugly man, but quite a gentleman; and that he treated me kindly, and I was content.’

We get a similar portrait of Paul Emanuel in Villette, as in this scene at the Hotel Crecy party: ‘Amongst the gentlemen, I may incidentally observe, I had already noticed by glimpses, a severe, dark, professorial outline, hovering aloof in an inner saloon, seen only in vista. M. Emanuel knew many of the gentlemen present, but I think was a stranger to most of the ladies, excepting myself; in looking towards the hearth, he could not but see me, and naturally made a movement to approach; seeing, however, Dr. Bretton also, he changed his mind and held back. If that had been all, there would have been no cause for quarrel; but not satisfied with holding back, he puckered up his eyebrows, protruded his lip, and looked so ugly that I averted my eyes from the displeasing spectacle.’

In short there can be no doubt in my mind that without Brussels and Monsieur Heger there could have been no such brilliantly realised characters as Rochester and Monsieur Emanuel, and therefore neither Jane Eyre nor Villette. More specifically it seems to me that these characters, and the novels they loom over, could not have existed without the manner of Charlotte Brontë’s exit from Brussels at the dawn of 1844. If she had left contended and happy these images would not have continued to brood in her mind only to burst forth so dramatically onto paper in the years to come.

We can never know what moments today which may seem sad and inauspicious may yet yield treasures of gold in the future, so whatever this new year throws at you keep going and keep believing in yourself. Charlotte Brontë did, and we can all be thankful for that.

Today also marks the anniversary of the death of Madame Clare Heger. She passed away on the 9th of January 1890. Madame Heger also played a vital role in the Brontë literary story, although neither she nor Charlotte could have known it at the time. There are plenty more stories to tell, so I hope you can join me again next week for another new Brontë blog post. A bientot!