It was Anne Brontë’s 202nd birthday on Monday, as she was born in Thornton Parsonage on 17th January 1820. As it’s still Anne’s birthday week this week’s blog will continue our Anne Brontë celebrations.

Over the years we’ve looked at Anne’s remarkable talent as a writer, and the wonderful (if all too brief) body of work it produced. Early twentieth century author George Moore famously said, ‘If Anne Brontë had lived ten years longer, she would have taken a place beside Jane Austen, perhaps even a higher place.’ Moore certainly knew and appreciated Anne’s writing, but he hadn’t known Anne herself. In this celebratory post we’re going to step away from Anne the writer and look at Anne Brontë the person, by examining the testimony of people who had met and known her. Let’s start with an obvious source: Anne’s elder sister Charlotte:

Charlotte Brontë

‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, by Acton Bell, had likewise an unfavourable reception. At this I cannot wonder. The choice of subject was an entire mistake. Nothing less congruous with the writer’s nature could be conceived. The motives which dictated this choice were pure, but, I think, slightly morbid. She had, in the course of her life, been called on to contemplate, near at hand, and for a long time, the terrible effects of talents misused and faculties abused: hers was naturally a sensitive, reserved, and dejected nature; what she saw sank very deeply into her mind; it did her harm. She brooded over it till she believed it to be a duty to reproduce every detail (of course with fictitious characters, incidents, and situations), as a warning to others. She hated her work, but would pursue it. When reasoned with on the subject, she regarded such reasonings as a temptation to self-indulgence. She must be honest; she must not varnish, soften, nor conceal. This well-meant resolution brought on her misconstruction, and some abuse, which she bore: as it was her custom to bear whatever was unpleasant, with mild, steady patience. She was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life… Anne’s character was milder and more subdued; she wanted the power, the fire, the originality of her sister [Emily], but was well endowed with quiet virtues of her own. Long-suffering, self-denying, reflective, and intelligent, a constitutional reserve and taciturnity placed and kept her in the shade, and covered her mind, and especially her feelings, with a sort of nun-like veil, which was rarely lifted. Neither Emily nor Anne was learned; they had no thought of filling their pitchers at the well-spring of other minds; they always wrote from the impulse of nature, the dictates of intuition, and from such stores of observation as their limited experience had enabled them to amass. I may sum up all by saying, that for strangers they were nothing, for superficial observers less than nothing; but for those who had known them all their lives in the intimacy of close relationship, they were genuinely good and truly great.’

In this biographical notice Charlotte intended to introduce the real Acton (Anne) and Ellis (Emily) Bell to the reading public for the first time. In doing so, however, she also sought to protect them against some of the criticism their work had faced, by portraying them as unworldly women with little education or knowledge of literature. This was far from the whole picture, as Anne was well educated, well read and hugely knowledgeable on a wide range of subjects (for example, she was the only Brontë sister who knew Latin and Greek to any extent). To get a true image of Charlotte’s view of Anne we need to turn to that concluding sentence: ‘genuinely good and truly great.’ Away from her over-protective defence of her youngest sibling, there can be no doubt that Charlotte loved Anne dearly. As Charlotte Brontë wrote in her moving elegy, Anne was ‘the darling of my life’ and ‘one I would have died to save.’

Ellen Nussey

‘Anne – dear, gentle Anne – was quite different in appearance from the others. She was her aunt’s favourite. Her hair was a very pretty light brown, and fell on her neck in graceful curls. She had lovely violet-blue eyes, fine pencilled eyebrows, and clear, almost transparent complexion.’

George Smith

‘That particular Saturday morning I was at work in my room, when a clerk reported that two ladies wished to see me. I was very busy and sent out to ask their names. The clerk returned to say that the ladies declined to give their names, but wished to see me on a private matter. After a moment’s hesitation I told him to show them in. I was in the midst of my correspondence, and my thoughts were far away from ‘Currer Bell’ and ‘Jane Eyre’. Two rather quaintly dressed little ladies, pale-faced and anxious-looking, walked into my room… This [Charlotte and Anne’s 1848 visit to London] is the only occasion on which I saw Anne Brontë. She was a gentle, quiet, rather subdued person, by no means pretty, yet of a pleasing appearance. Her manner was curiously expressive of a wish for protection and encouragement, a kind of constant appeal which invited sympathy.’

Incidentally, from Smith’s memoirs we also get an account of Charlotte’s reaction upon first seeing her portrait by George Richmond. Richmond was renowned for ‘beautifying’ his subjects (which is perhaps why he was so in demand), and it seems that Charlotte was moved by how much her portrait actually looked like Anne: ‘Mr Richmond mentioned that when she saw the portrait (she was not allowed to see it before it was finished) she burst into tears, exclaiming that it was so like her sister Anne, who had died the year before.’

Nancy Garrs

‘When the family removed to Haworth she accompanied them, remaining with them many years as cook, her younger sister taking her place in the nursery. She has many stories to relate of the kindly disposition of Charlotte, the wilfulness of Branwell, the hot temper of Emily, and the tenderness of Anne.’

Now we have seen what some of those who knew Anne best thought of her, let’s turn to the thoughts of Haworth villagers who met Anne during the course of their everyday lives:

Tabitha Ratcliffe

‘Her most interesting relic is a photograph on glass of the three sisters. “I believe Charlotte was the lowest and the broadest, and Emily was the tallest. She’d bigger bones and was stronger looking and more masculine, but very nice in her ways,” she comments. “But I used to think Miss Anne looked the nicest and most serious like; she used to teach at Sunday school. I’ve been taught by her and by Charlotte and all.” And it is on Anne that her glance rests as she says, “I think that is a good face.” There is no doubt which of the sisters of Haworth was Mrs Ratcliffe’s favourite.’

Sarah Wood

‘Miss Parry also visited Mrs Sarah Wood, who keeps a little clothier’s shop in the village, and has many souvenirs of the Brontë family. “Do I remember the Brontës?” was her greeting. “I should rather think I did. Miss Charlotte was my Sunday-school teacher. She was nice. But Miss Anne was my favourite: such a gentle creature.”’

Haworth church guide

‘Standing beside Charlotte’s last resting-place, I questioned my conductor respecting her, and found him at once ready and willing to oblige me with all the information in his possession. He had been but a little boy, he said, when all the family were living, but he remembered the three sisters well, and had often run errands for Mr Patrick. They used to take a great deal of notice of him when he was little; but Miss Annie was his favourite, perhaps because she always paid him so much attention. Baking-day never came round at the parsonage without her remembering to make a little cake or dumpling for him, and she seldom met him without having something good and sweet to bestow upon him.’

Anonymous Haworth villager

‘But it needed not the presence of the children and gossips of the village to people it; for the whole place seemed haunted with the faces and forms of those to whom this ‘long, unlovely street’ had once been so familiar. There was Charlotte Bronte herself – ‘a little woman, plainly dressed, and with nothing particular to notice in her appearance’, setting off bravely on a long walk to Keighley for the books which awaited her at the circulating library. There was Emily, with masculine gait, striding down towards the brook, followed by the dogs she loved so well. There was Anne, gentle and timid – ‘the loveliest of them all’, says one who knew them well – passing from house to house amongst the parishioners, with a kind word and a sweet smile for everyone.’

Now we have as complete a picture of Anne Brontë as a person and not just as a writer that we can get today. As Anne Brontë herself wrote at the conclusion of her brilliant debut novel Agnes Grey: ‘And now I think I have said sufficient.’

It is testimony to Anne’s character that we see a very uniform picture of Anne emerging. She is always described as tender, gentle and kind. When we walk the cobbled streets of Haworth we can picture Anne walking them, handing out buns to children and smiles to all. The Haworth villagers were seemingly of one opinion; Anne was ‘the loveliest of them all’ and their favourite. And, with no offence to her wonderful siblings, she is my favourite too.

I hope to see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post, and I hope you’ve enjoyed Anne Brontë’s birthday week.

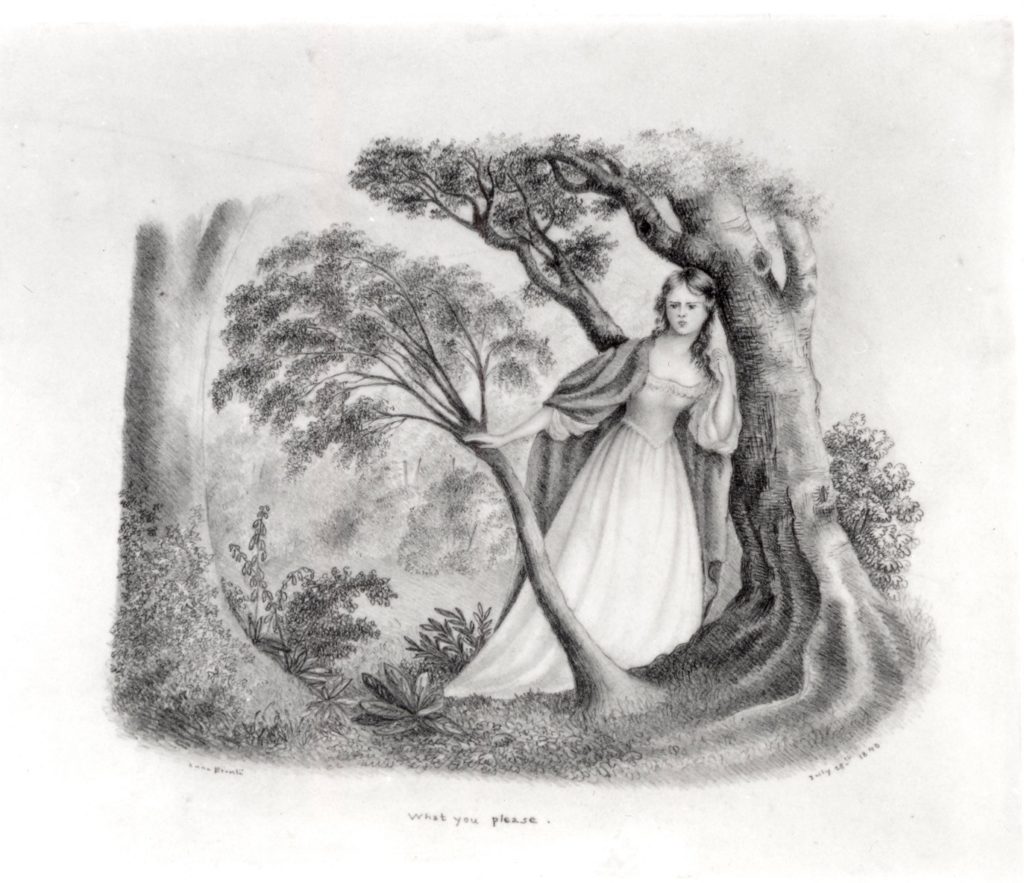

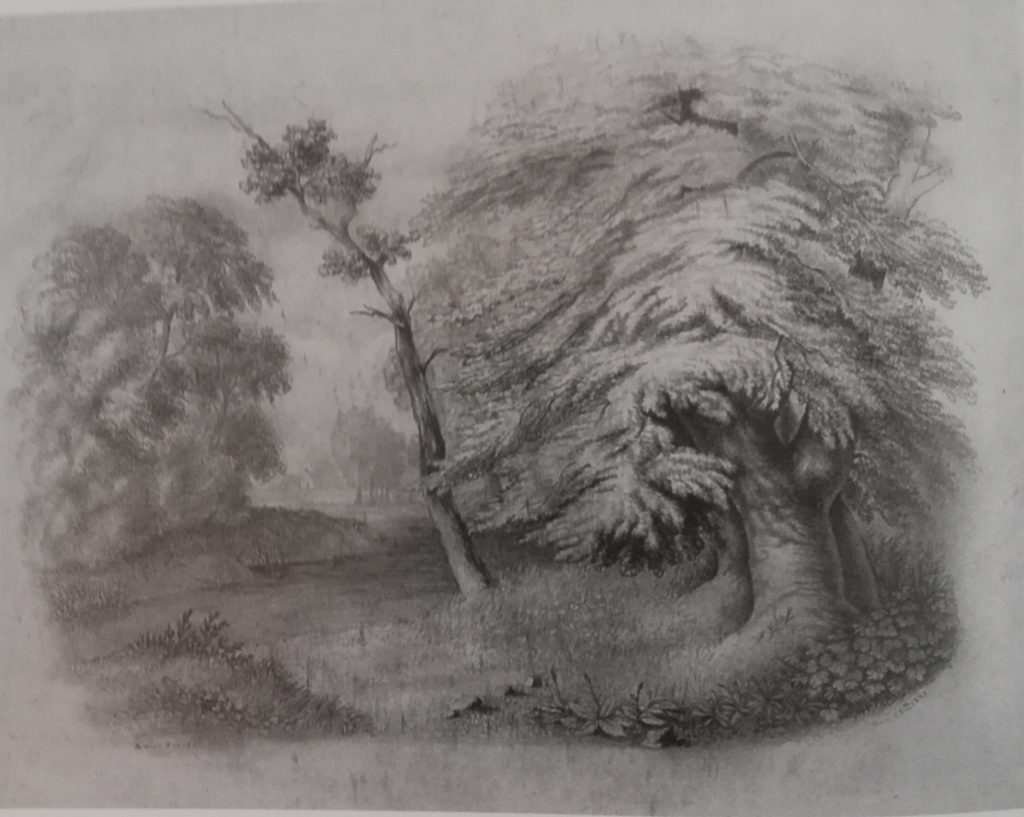

Thanks for the wonderful birthday post. I was wondering where the beautiful drawings are located and if there are more? It seems that all three sisters were excellent artists. Is that correct?

A very interesting article.