We can always turn to the Brontës and classic novels in troubled or uncertain times. Let’s be thankful for that, for the world has certainly thrown us all a curve ball since last Sunday’s Brontë blog post. In Yorkshire, or wherever you are reading this, it’s easy to feel isolated from all that’s going on, but the people of Ukraine are facing a very real struggle at this moment from which I sincerely hope they prevail. In today’s post we’re going to look at the Brontës and war.

Britain had a very recent history of warfare at the time that the Brontë siblings were born and grew up, for we had just emerged from the Napoleonic Wars. Indeed, the pivotal Battle of Waterloo took place less than a year before the birth of Charlotte Brontë and after the birth of her elder sisters Maria and Elizabeth. The Brontës grew up with the threat of war diminished, but the country remained on its guard and the newspapers and magazines the Brontës loved to read were full of tales of war and heroism.

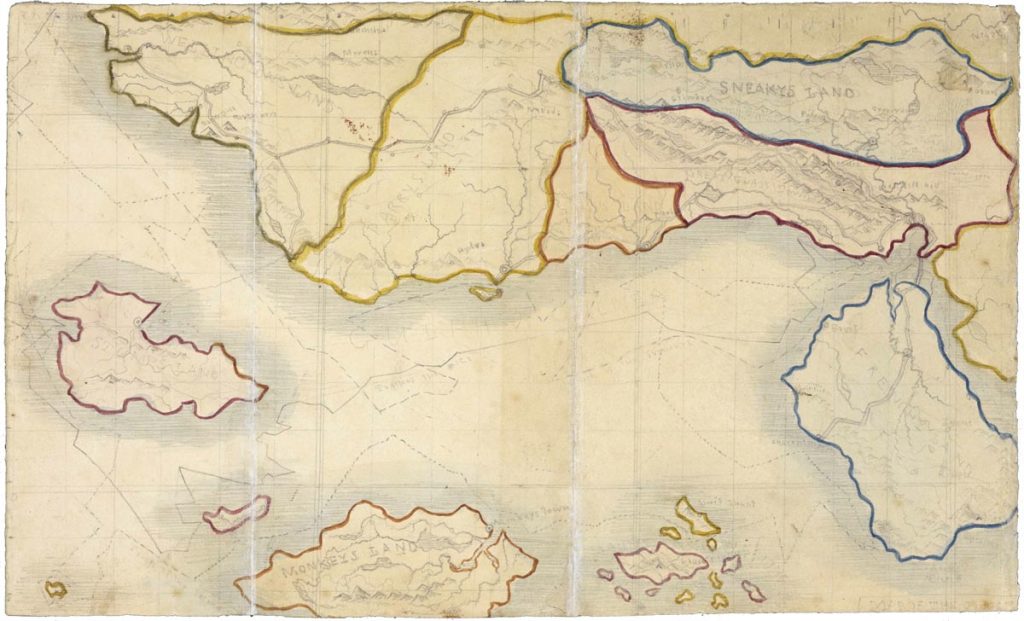

Young minds then, just like young minds today, were easily fired by such tales, and it led to a pivotal moment in the Brontë story and the story of English literature. We’ve looked before at how Patrick Brontë’s 1826 gift of twelve toy soldiers to his son Branwell led to a series of games based around ‘the twelve’ and then on to stories and tiny books about them. The Brontë imagination was in top gear, and the rest is history. Here’s how a young Charlotte Brontë remembered the event:

“Papa bought Branwell some wooden soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night, and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed, and I snatched up one and exclaimed: ‘This is the Duke of Wellington! This shall be the Duke!’ when I had said this Emily likewise took one up and said it should be hers; when Anne came down, she said one should be hers. Mine was the prettiest of the whole, and the tallest, and the most perfect in every part. Emily’s was a grave-looking fellow, and we called him ‘Gravey’. Anne’s was a queer little thing, much like herself, and we called him ‘Waiting-boy’. Branwell chose his, and called him Buonaparte.”

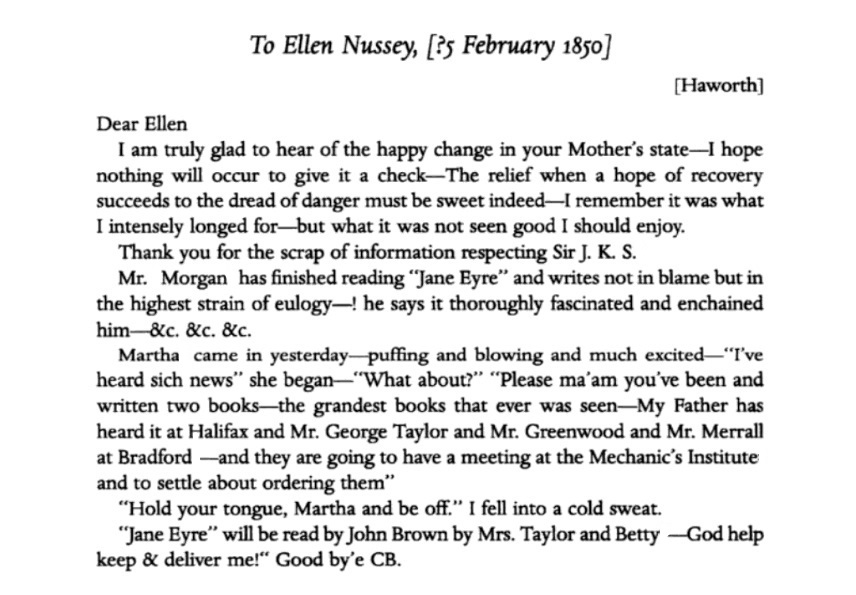

Charlotte hero worshipped the great military leader, and later Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, and thanks to the machinations of her publisher George Smith she finally met him in June 1850 after which she excitedly wrote to Ellen Nussey calling him, “a real grand old man.”

The Brontës’ fascination with all things military was also inspired, no doubt, by their father’s own leanings. He was a patriotic man who took great pride and interest in Britain’s military activities; so much so that Charlotte’s friend Ellen once said of him:

“Mr Brontë’s tastes led him to delight in the perusal of battle-scenes, and in following the artifice of war, had he entered on military service instead of ecclesiastical he would probably have had a very distinguished career.”

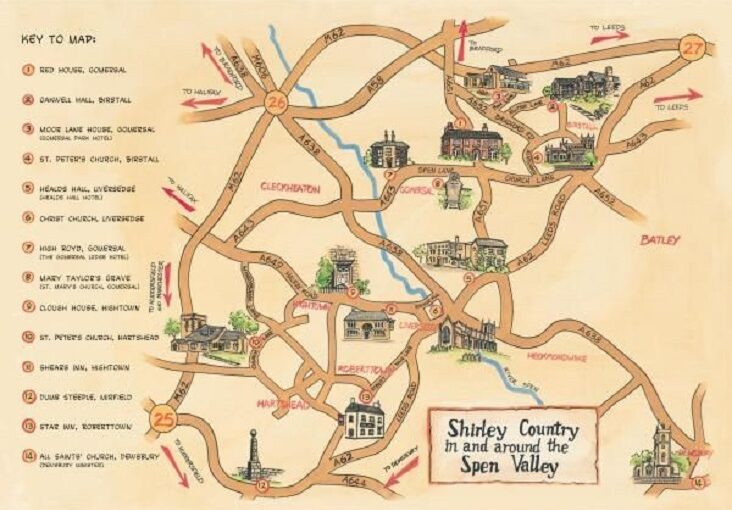

War, and especially the cessation of it, also touched greatly upon the life of another great friend of Charlotte Brontë: Mary Taylor (whose 205th birthday was yesterday the 26th February, by the by). Charlotte met Mary and Ellen at Roe Head school near Mirfield, but Mary was from a far more comfortable background than the curate’s daughter from Haworth. The Taylors lived at the large and attractive Red House in Gomersal, and their finances seemed to be so sound that they even had their own bank. The source of the Taylor riches was cloth, and one particular variety of it, for Mary’s father Joshua (immortalised by Charlotte as Hiram Yorke in Shirley) had a hugely lucrative contract to manufacture the red fabric used to make uniforms for the British army. Unfortunately as peace descended, at least temporarily across Europe, the demand for this cloth collapsed and Joshua Taylor died bankrupt in 1840.

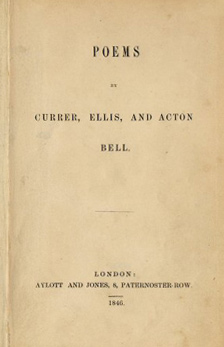

The Brontë juvenilia, in particular, is full of stories of intrigue, betrayal and war. From Glasstown to Angria and then onto Gondal, the domain of Emily and Anne Bronte’s earliest writing, the influence of those toy soldiers and the tales they inspired can still be seen.

For Emily Brontë especially Gondal was not confined to childhood, it was a lifelong passion, so we see war-inspired poetry throughout her life. In 1837 Emily wrote this typically boisterous poem of Gondalian conflict, ‘Song by Julius Angora’:

‘Awake! awake! how loud the stormy morning

Calls up to life the nations resting round;

Arise! arise! is it the voice of mourning

That breaks our slumber with so wild a sound?

The voice of mourning? Listen to its pealing;

That shout of triumph drowns the sigh of woe.

Each tortured heart forgets its wonted feeling;

Each faded cheek resumes its long-lost glow.

Our souls are full of gladness; God has given

Our arms to victory, our foes to death;

The crimson ensign waves its sheet in heaven,

The sea-green Standard lies in dust beneath.

Patriots, no stain is on your country’s glory;

Soldiers, preserve that glory bright and free.

Let Almedore, in peace, and battle gory,

Be still a nobler name for victory!’

By 1843, however, Emily’s ‘On The Fall Of Zalona’ shows a very different side of war, with lines including:

‘What do those brazen tongues proclaim?

What joyous fête begun –

What offerings to our country’s fame –

What noble victory won?

Go, ask that solitary sire

Laid in his house alone;

His silent hearth without a fire –

His sons and daughters gone – Go, ask those children in the street

Beside their mother’s door;

Waiting to hear the lingering feet

That they shall hear no more.

Ask those pale soldiers round the gates

With famine-kindled eye –

They’ll say, “Zalona celebrates

The day that she must die!”…

Heaven help us in this awful hour!

For now might faith decay –

Now might we doubt God’s guardian power

And curse, instead of pray.’

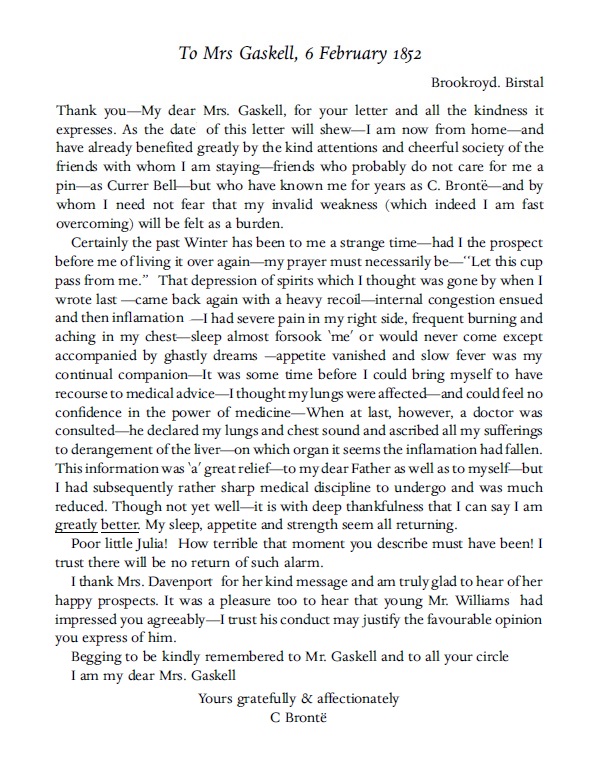

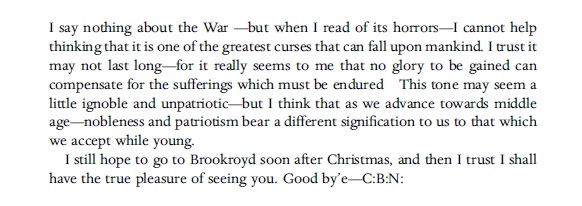

Charlotte Brontë too turned away from her earlier jingoistic view of war. By 1853 Britain was at war once more, this time fighting Russia in the Crimean War. Charlotte and Patrick both helped to raise funds for the Patriotic Fund, which gave money to wounded soldiers and to the families of dead soldiers. In the postscript of a letter to Margaret Wooler dated 6th December 1854, in the aftermath of the charge of the Light Brigade (which heads this post) Charlotte gives this moving account of her attitude to war, and why it has changed:

Let us hope for better news from Ukraine soon. In the meantime, we can find solace in the books we love so much. I hope you’ve been enjoying the daily Brontëdles, and I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.