Anne Brontë was a supremely talented poet from a family full of poetry lovers. Her poetry often gives us tantalising clues to moments in her life, as Anne herself admitted in Agnes Grey: ‘When we are harassed by sorrows or anxieties, or long oppressed by any powerful feelings which we must keep to ourselves, for which we can obtain and seek no sympathy from any living creature, and which yet we cannot, or will not wholly crush, we often naturally seek relief in poetry – and often find it, too.’ In today’s post we’re going to take a look at one such, very timely, poem: ‘In Memory of a Happy Day in February’ by Anne Brontë.

Unusually it was written in two sections written a long time apart, and these two parts feel distinctly different to each other, so even if we didn’t know we could guess when the poem had been set aside and then taken up again. This was certainly unusual but not unique for Anne for there is one other famous example of it, and it came right at the end of her all too brief life. Her final poem, which she left untitled but was posthumously titled ‘Last Lines’ by sister Charlotte Brontë, was begun on 7th January 1849 and completed on 28th January 1849 and charts the voyage from despair to acceptance after Anne Brontë was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the start of the year.

Let’s now take a look at a very different poem by Anne and remember that happy February day with her:

‘Blessed be Thou for all the joy

My soul has felt today!

O let its memory stay with me

And never pass away!

I was alone, for those I loved

Were far away from me,

The sun shone on the withered grass,

The wind blew fresh and free.

Was it the smile of early spring

That made my bosom glow?

‘Twas sweet, but neither sun nor wind

Could raise my spirit so.

Was it some feeling of delight,

All vague and undefined?

No, ’twas a rapture deep and strong,

Expanding in the mind!

Was it a sanguine view of life

And all its transient bliss –

A hope of bright prosperity?

O no, it was not this!

It was a glimpse of truth divine

Unto my spirit given

Illumined by a ray of light

That shone direct from heaven!

I felt there was a God on high

By whom all things were made.

I saw His wisdom and his power

In all his works displayed.

But most throughout the moral world

I saw his glory shine;

I saw His wisdom infinite,

His mercy all divine.

Deep secrets of his providence

In darkness long concealed

Were brought to my delighted eyes

And graciously revealed.

But while I wondered and adored

His wisdom so divine,

I did not tremble at his power,

I felt that God was mine.

I knew that my Redeemer lived,

I did not fear to die;

Full sure that I should rise again

To immortality.

I longed to view that bliss divine

Which eye hath never seen,

To see the glories of his face

Without the veil between.’

The first section of this powerful poem, up to the line ‘that shone direct from heaven!’ was written in February 1842, but the final section from ‘I felt there was a God on high’ was dated by Anne Brontë on November 10th 1842. Why the nine month gap, and why the change from a cheerful poem about a happy day to one about God’s power in the face of darkness and adversity?

It seems likely that when Anne Brontë started this composition she felt herself alone and far from loved her, but that some event occurred that lifted her spirits. The reason for this first feeling of isolation is easily discerned. At this time Anne had returned to her role of governess to the Robinson family of Thorp Green Hall near York, but her sisters Emily and Charlotte had just embarked on their voyage to Brussels. It must have seemed to Anne that she would not see her beloved siblings again all year – this vital cord of communion which she shared with Emily and Charlotte was now broken.

We can easily imagine the despondency this must have produced, and yet something in the poem has produced a positive effect which has turned the day into a happy one she has remembered forever – what could it be which has produced the metaphor of a ray of sunlight direct from heaven which has enraptured her mind? Perhaps the date of the composition of this poem is a clue?

All that we know for sure is that this poem was started in February of 1842, but it could well be that it was written at this time of February, perhaps on this very day or the one succeeding it? Let’s roll away the clouds – by this time, as far as I’m concerned and whatever some proof-burdened academics may say, Anne Brontë had fallen in love with William Weightman, assistant curate to her father back in Haworth.

We know that in 1840 and 1841 he had sent Valentine’s Day cards to the Brontë sisters, so it doesn’t stretch the imagination too much to think that he had sent one to Anne, the sister whose feelings he reciprocated, at Thorp Green in 1842. It is the receipt of this card, I feel, which has swept the trial of loneliness away and replaced it with the warming glow of love and remembrance.

The last line of the first section was surely intended by Anne to be the final line of a happy, uplifting poem, so why did she return to it and change its style from a secular poem to a religious poem? Once again the clue is in the date; by November 1842, alas, Anne’s circumstances were very different. William Weightman died of cholera contracted from a parishioner on 6th September 1842, and on 29th October 1842 Elizabeth Branwell, the aunt who was like a mother to Anne Brontë, followed him to the grave. It is in the direct aftermath of these two huge losses for Anne, and exactly a week after Aunt Branwell’s funeral, that Anne returned to her earlier verse. Just like her eponymous heroine Agnes, Anne has sought relief in poetry at a time when she is harassed by sorrows and anxiety.

Now we see Anne’s thoughts elevated skywards, to the loving rest that she now felt Weightman and her aunt were enjoying; to the compassion and goodness of God, to the faith which, even more than poetry, she could turn to in this dark time. With these two central figures in her life snatched away so suddenly, Anne now longs for immortality in Heaven herself, to see God, Weightman and her aunt face to face once more, without the veil of death between them.

The brilliance of this poem lies in its two separate sections, and the two separate stories it tells us. 1842 was a year of joys and sorrows for Anne, but she always had a happy day in February to look back on.

I hope you all have many happy days in this February, and that, unlike me, you will get something more exciting in the post than bills and flyers on Valentine’s Day tomorrow. May you have a great day full of love, happiness and good books to read. I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post.

excellent, eye-opening analogy- Anne immensely courageous in double grief, esp for WW hoped by all her future.

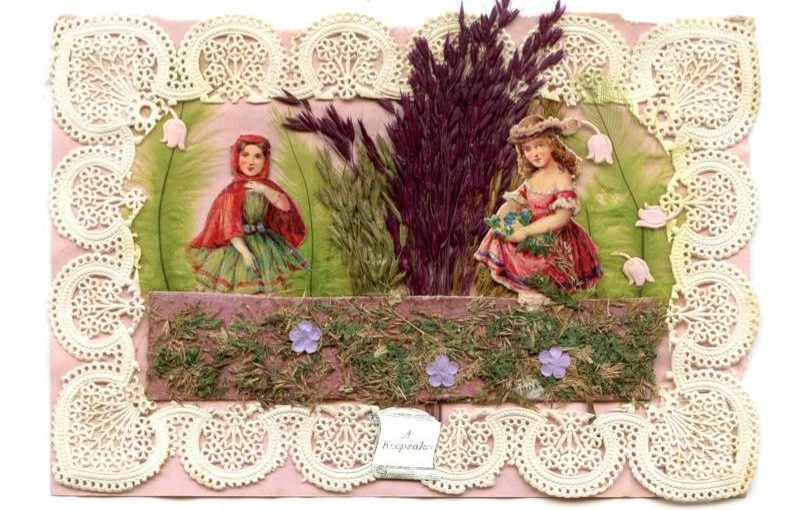

The drawings, WW’s enrapturing, determined angelic profile above, and Anne’s porcelain beauty of demure, steadfast resolve in rustic folds.. are not the lines of Charlotte’s incremental hand. They both gifts from teacher, mentor, hero and friend ’33-’39, famous son of pap’s pal John, the brave, frowned upon angel reformist Edwin Landseer. Is convenient hope and explanation to attribute them and other fine drawings among Bronte artefacts to one or other of the siblings themselves, oblivious or denying fact Bran had art acumen of 8 y/o bereft of talent, and density of any kind never contributing to C’s drawings.

A very interesting essay. Death was always so close. I can only compare it to the worst days of the pandemic now but for the Bronte’s it was a constant feature. Most of us will not lose loved ones until later in life – they were just little girls when they started losing siblings. And Anne was only 22 when she lost her beloved aunt and the curate she was in love with. People must have matured much earlier than we do, I think, with the spectre of death always hovering.

I have always been enthralled by the Bronte sisters all my life,

I have read their books and have followed everything i can about them…. But the strange events when every time i started to read the life of Charlotte Bronte by Elizabeth Gaskell I always reached halfway through that book and then the book would go missing and never was seen again… this happen to me on four occasions over the years when i lived in England.

Thanks for this wonderful analysis of Anne’s beautiful poem.

It would be good to get the background for some of her other poems.