Here in the United Kingdom we’re celebrating mother’s day. At first Mothering Sunday wasn’t about maternal parents at all, it was a day when domestic servants were given a day off to return to their mother parish. Today, of course, it’s a celebration of wonderful mothers so it seems a perfect day to look at mothers, and the absence of mothers, in Brontë novels.

The first thing that jumps out at us when considering protagonists’ mothers in these great books is that they are completely absent in the novels of Charlotte Brontë. From Jane Eyre to Lucy Snowe and Shirley Keeldar there’s not a mother to be found. William Crimsworth, the eponymous Professor, is also an orphan at the start of Charlotte’s posthumously published novel.

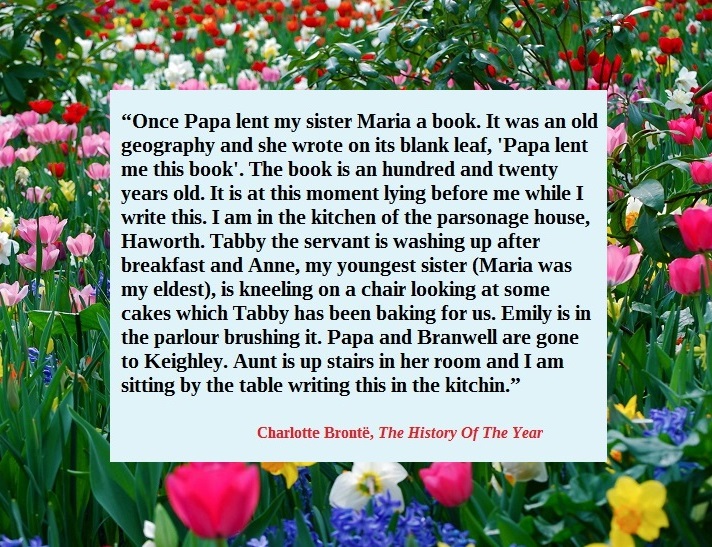

Why should this be? We shall see that both Anne and Emily Brontë included mothers and motherhood in their novels, so could it be that the memory of an actual mother was too painful for Charlotte to set down in ink? As a one year old baby and a three year old infant at the time of their mother’s death Anne and Emily would have had little recollection of Maria, but the blow to five year old Charlotte in 1821 must have been one that remained with her forever. In her novels, therefore, we see the protagonists being raised by uncles and aunts of varying degrees of benevolence, just as Charlotte and her siblings were raised by their Aunt Branwell. Do we get a portrait of Elizabeth Branwell in Charlotte’s novels? We’ll return to that later, but first let’s look at mothers in the novels of Anne and Emily after a SPOILER ALERT: If you haven’t yet read any of the books below you may want to avoid that particular section!

Wuthering Heights

Emily’s epic novel is all encompassing when it comes to family relationships and human emotions, which is probably why some people (myself included) think it’s the greatest book ever written. At the start of Nelly’s recollection we find the Earnshaw family as a happy family unit, one into which Mr Earnshaw brings an orphan he has found on a journey to Liverpool: the orphan is of course Heathcliff. This brings about a cataclysmic chain of events which has its roots in the blossoming love between Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff. My own opinion is that Heathcliff is actually the illegitimate son of Earnshaw; why else would he bring him back across the Pennines and raise him as his own son (we can similarly surmise that Adele is Rochester’s illegitimate daughter, such events were far from rare in the moneyed classes of the time).

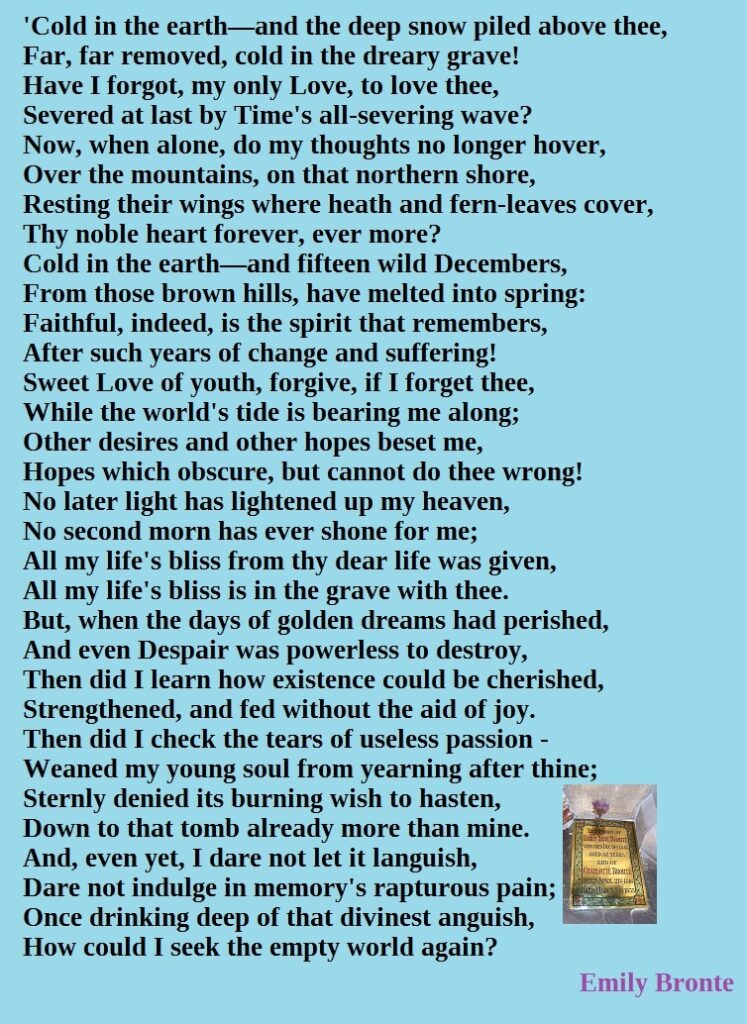

In this light, the relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff takes on a rather darker hue than the one it already has. Catherine briefly becomes a mother, but she is not to experience the joys and tribulations of motherhood. By then Catherine Linton she dies after giving birth to Cathy, and another chapter in Heathcliff’s quest for revenge is born.

Catherine had received a divine punishment, but why? Was it because she had not been faithful to Heathcliff, or because she had fallen in love (unknowingly) with her half-brother? Emily Brontë gave us another reason, and it was rooted in the folklore she loved. From her Aunt Branwell, Emily would have heard tales of the Cornwall which had been home to her aunt and mother. On the outskirts of Penzance is an ancient ringed stone called the Men-an-Tol. Local legend says that if a woman crawls backwards through the stone by moonlight she will fall pregnant within a year. There’s a similar legend on the outskirts itself relating to an ancient outcrop called Ponden Kirk. It is said that if two lovers wander through its opening, known as the fairy cave, together they must marry in a year and the woman will have a child – if they do not marry within a year, the woman will die and her spirit will be confined in the kirk forever. In the novel, Catherine and Heathcliff went through this very same opening on the moors (called Penistone Crag in the book); they did not marry, and so Catherine has to die. She acknowledges as much to Nelly as she approaches her moment of duality, the moment that will bring new life and end her own:

‘This bed is the fairy cave under Penistone Crag, and you are gathering elf-bolts to hurt our heifers; pretending, while I am near, that they are only locks of wool. That’s what you’ll come to fifty years hence: I know you are not so now. I’m not wandering, you’re mistaken, or I should believe you really were that withered hag, and I should think I was under Penistone Crag.’

Agnes Grey

Unlike other Brontë heroes and heroines it is the father who Agnes loses early in the novel, and her mother remains a strong, loving, supportive mother throughout. This may be because of the strong bond that Anne had formed with Elizabeth Branwell; they shared a room, and Anne was acknowledged as her aunt’s favourite – in effect, Aunt Branwell had become a mother to Anne Brontë.

Agnes’s mother comes from a wealthy background, just as Anne’s mother and aunt had, and after the tribulations of life as a governess for Agnes she later returns to her mother’s side and they form a school together. Finally, of course, Agnes Grey, or Agnes Weston as she now is, herself becomes a mother, which we are told at the very climax of the novel:

‘Our children, Edward, Agnes, and little Mary, promise well; their education, for the time being, is chiefly committed to me; and they shall want no good thing that a mother’s care can give. Our modest income is amply sufficient for our requirements: and by practising the economy we learnt in harder times, and never attempting to imitate our richer neighbours, we manage not only to enjoy comfort and contentment ourselves, but to have every year something to lay by for our children, and something to give to those who need it. And now I think I have said sufficient.’

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

Anne Brontë was a brilliant novelist, and both her books present images of the ideal of motherhood as Anne saw it. In Agnes Grey we see motherhood as perhaps Anne herself dreamed of living it one day: raising her children with love and compassion in a happy family unit. In The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall we see a very different portrait of motherhood.

Helen, the tenant of the title, has endured a loveless and abusive marriage, but she is determined to protect her son Arthur at any cost. She takes the momentous decision to leave her husband, change her name, and make her own way in life through her artistic endeavours.

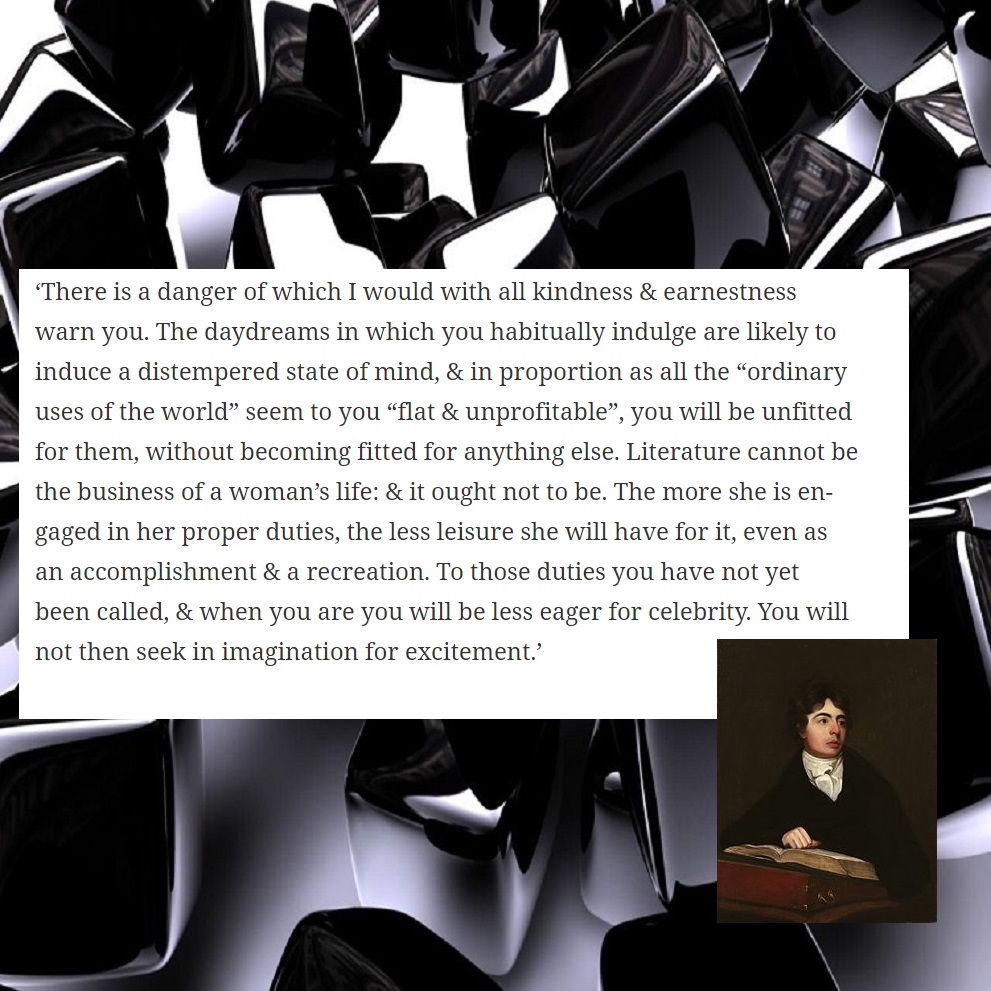

To many readers this would have been a scandalous decision, and yet it became a runaway success which resonated with readers. Anne wasn’t bound by religious and social conventions of the time, she was saying that Helen was a perfect example of motherhood: someone who put love of her child above all other things, and who would protect them at any cost. Helen also delivers a powerful manifesto of how to raise a son, to the horror of those who hear it:

‘“I will lead him by the hand, Mr. Markham, till he has strength to go alone; and I will clear as many stones from his path as I can, and teach him to avoid the rest – or walk firmly over them, as you say;—for when I have done my utmost, in the way of clearance, there will still be plenty left to exercise all the agility, steadiness, and circumspection he will ever have. – It is all very well to talk about noble resistance, and trials of virtue; but for fifty – or five hundred men that have yielded to temptation, show me one that has had virtue to resist. And why should I take it for granted that my son will be one in a thousand? – and not rather prepare for the worst, and suppose he will be like his – like the rest of mankind, unless I take care to prevent it?… Well, then, it must be that you think they are both weak and prone to err, and the slightest error, the merest shadow of pollution, will ruin the one, while the character of the other will be strengthened and embellished – his education properly finished by a little practical acquaintance with forbidden things. Such experience, to him (to use a trite simile), will be like the storm to the oak, which, though it may scatter the leaves, and snap the smaller branches, serves but to rivet the roots, and to harden and condense the fibres of the tree. You would have us encourage our sons to prove all things by their own experience, while our daughters must not even profit by the experience of others. Now I would have both so to benefit by the experience of others, and the precepts of a higher authority, that they should know beforehand to refuse the evil and choose the good, and require no experimental proofs to teach them the evil of transgression. I would not send a poor girl into the world, unarmed against her foes, and ignorant of the snares that beset her path; nor would I watch and guard her, till, deprived of self-respect and self-reliance, she lost the power or the will to watch and guard herself; – and as for my son – if I thought he would grow up to be what you call a man of the world – one that has ‘seen life,’ and glories in his experience, even though he should so far profit by it as to sober down, at length, into a useful and respected member of society – I would rather that he died to-morrow! – rather a thousand times!” she earnestly repeated, pressing her darling to her side and kissing his forehead with intense affection.’

After a long series of trials, Helen finally finds the contentment and happiness she deserves.

Shirley

At the start of this post I claimed that none of Charlotte’s protagonists had a mother, but to be fair that isn’t completely true. Shirley Keeldar may be the titular heroine, but Caroline Helstone (who is in many ways based upon Anne Brontë) is the real heroine in the novel and appears in it to a much greater extent.

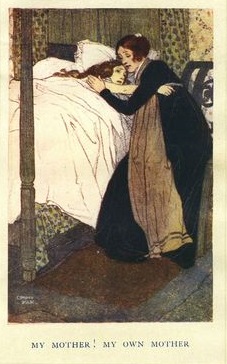

At the opening it appears that Caroline too is an orphan, but as she lies seemingly on her deathbed we receive the moving revelation that Mrs Pryor is actually her mother:

‘”I believe grief is, and always has been, my worst ailment. I sometimes think if an abundant gush of happiness came on me I could revive yet.”

“Do you wish to live?”

“I have no object in life.”

“You love me, Caroline?”

“Very much – very truly – inexpressibly sometimes. Just now I feel as if I could almost grow to your heart.

“I will return directly, dear,” remarked Mrs. Pryor, as she laid Caroline down.

Quitting her, she glided to the door, softly turned the key in the lock, ascertained that it was fast, and came back. She bent over her. She threw back the curtain to admit the moonlight more freely. She gazed intently on her face.

“Then, if you love me,” said she, speaking quickly, with an altered voice; “if you feel as if, to use your own words, you could ‘grow to my heart,’ it will be neither shock nor pain for you to know that that heart is the source whence yours was filled; that from my veins issued the tide which flows in yours; that you are mine – my daughter – my own child.”

“Mrs. Pryor – ”

“My own child!”

“That is – that means – you have adopted me?”

“It means that, if I have given you nothing else, I at least gave you life; that I bore you, nursed you; that I am your true mother. No other woman can claim the title; it is mine.”

“But Mrs. James Helstone – but my father’s wife, whom I do not remember ever to have seen, she is my mother?”

“She is your mother. James Helstone was my husband. I say you are mine. I have proved it. I thought perhaps you were all his, which would have been a cruel dispensation for me. I find it is not so. God permitted me to be the parent of my child’s mind. It belongs to me; it is my property—my right. These features are James’s own. He had a fine face when he was young, and not altered by error. Papa, my darling, gave you your blue eyes and soft brown hair; he gave you the oval of your face and the regularity of your lineaments – the outside he conferred; but the heart and the brain are mine. The germs are from me, and they are improved, they are developed to excellence. I esteem and approve my child as highly as I do most fondly love her.”

“Is what I hear true? Is it no dream?”

“I wish it were as true that the substance and colour of health were restored to your cheek.”

“My own mother! is she one I can be so fond of as I can of you? People generally did not like her – so I have been given to understand.”

“They told you that? Well, your mother now tells you that, not having the gift to please people generally, for their approbation she does not care. Her thoughts are centred in her child. Does that child welcome or reject her?”

“But if you are my mother, the world is all changed to me. Surely I can live. I should like to recover -”

“You must recover. You drew life and strength from my breast when you were a tiny, fair infant, over whose blue eyes I used to weep, fearing I beheld in your very beauty the sign of qualities that had entered my heart like iron, and pierced through my soul like a sword. Daughter! we have been long parted; I return now to cherish you again.”

She held her to her bosom; she cradled her in her arms; she rocked her softly, as if lulling a young child to sleep.

“My mother – my own mother!”’

This section of the novel was written after the tragic death of Anne Brontë. Charlotte gives Mrs Pryor as mother to Caroline just as Aunt Branwell had been a mother to Anne: this is Charlotte’s portrait of Aunt Branwell, and in it we see the love and respect she had for her. Aunt Branwell was often ridiculed (by Mary Taylor for example) for the outdated black dress that she habitually wore, but she gave freely of her own money to help her nieces and nephews rather than spending it on herself. In Shirley we see Charlotte acknowledging this as she describes similar actions by Mrs Pryor:

‘”Mamma, I am determined you shall not wear that old gown any more. Its fashion is not becoming; it is too strait in the skirt. You shall put on your black silk every afternoon. In that you look nice; it suits you. And you shall have a black satin dress for Sundays – a real satin, not a satinet or any of the shams. And, mamma, when you get the new one, mind you must wear it.”

“My dear, I thought of the black silk serving me as a best dress for many years yet, and I wished to buy you several things.”

“Nonsense, mamma. My uncle gives me cash to get what I want. You know he is generous enough; and I have set my heart on seeing you in a black satin. Get it soon, and let it be made by a dressmaker of my recommending. Let me choose the pattern. You always want to disguise yourself like a grandmother. You would persuade one that you are old and ugly. Not at all! On the contrary, when well dressed and cheerful you are very comely indeed; your smile is so pleasant, your teeth are so white, your hair is still such a pretty light colour. And then you speak like a young lady, with such a clear, fine tone, and you sing better than any young lady I ever heard. Why do you wear such dresses and bonnets, mamma, such as nobody else ever wears?”

“Does it annoy you, Caroline?”

“Very much; it vexes me even. People say you are miserly; and yet you are not, for you give liberally to the poor and to religious societies – though your gifts are conveyed so secretly and quietly that they are known to few except the receivers.”’

We see mothers of all kinds in the Brontë novels, but above all else we see love. Whether you are a mother, have a mother, or especially if you are missing your mother today, I send you my love and gratitude for all the good things you have done in your life, all the happiness you have spread – perhaps without even realising it. Have a great day, and I will see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post.