Emily Brontë was a brilliant wordsmith; not only did she write possibly the greatest novel ever, Wuthering Heights, she was also a first class poet. There can be little doubt that Emily was consistently the best poet of the Brontë siblings, and she was also one of the greatest English poets of the nineteenth century – full stop. Her verse encompasses a broad range of subjects, but there is one subject she returned to again and again. In fact it’s the title of a poem that Emily composed on this day in 1845: ‘Death’.

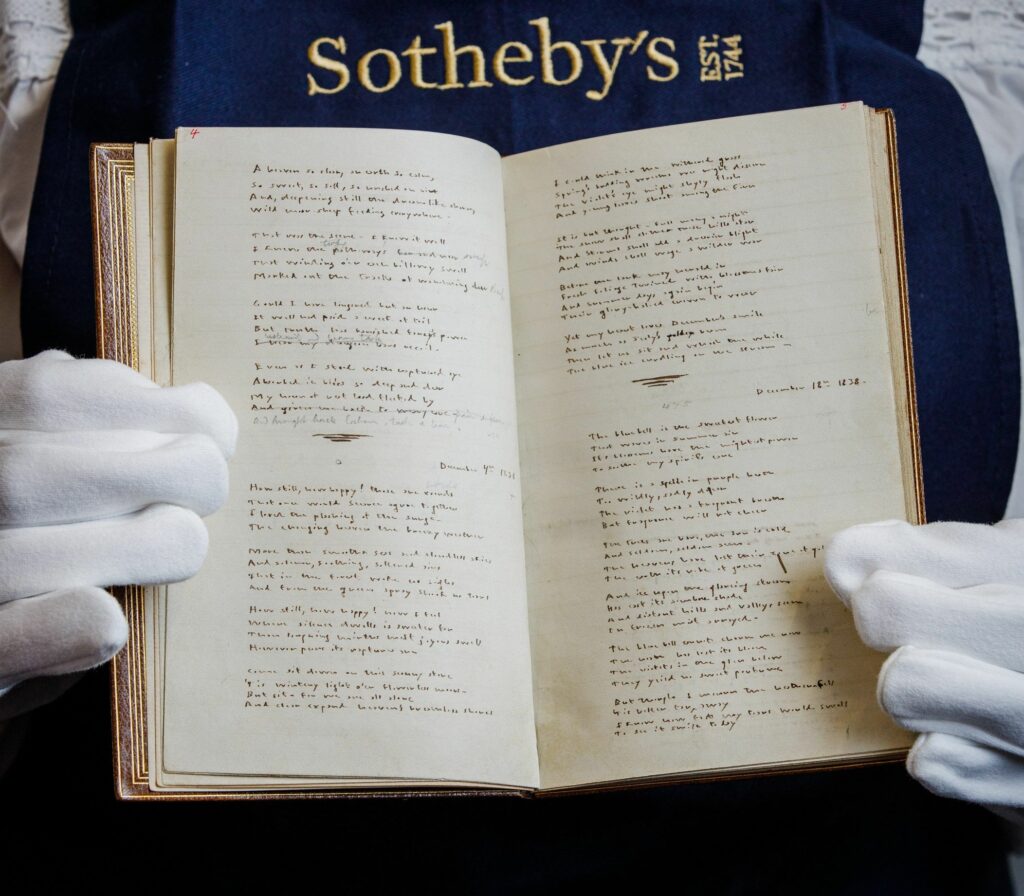

Before we go any further I will say that this post contains some depictions of death, in Emily’s own words, that some people may find distressing. If you think they may upset you then please give this post a miss and return next week. We’ll reproduce the poem in full at the end of this post, and it’s well worth waiting for; the manuscript is still extant, and we see it dated 10th April 1845 in Emily’s own hand. You may be able to see it yourself before too long, because it was one of the poems in Emily’s poetry manuscript book which formed the highlight of the Honresfield Library collection recently saved for the nation.

It’s a complex and yet easy to read poem, but it’s far from the only time that Emily considered the subject matter. We also have, for example, ‘A Death-Scene’ in which Emily describes in moving simplicity the final moments of a man, Edward, ending with:

‘Then his eyes began to weary,

Weighed beneath a mortal sleep;

And their orbs grew strangely dreary,

Clouded, even as they would weep.

But they wept not, but they changed not,

Never moved, and never closed;

Troubled still, and still they ranged not –

Wandered not, nor yet reposed!

So I knew that he was dying –

Stooped, and raised his languid head;

Felt no breath, and heard no sighing,

So I knew that he was dead.’

We also have Emily’s long, epic poem ‘The Death of A.G.A.’ which ends:

‘That death, has wronged us more than thee!

Thy passionate youth was nearly past

The opening sea seemed smooth at last

Yet vainly flowed the calmer wave

Since fate had not decreed to save –

And vain too must the sorrow be

Of those who live to mourn for thee;

But Gondal’s foes shall not complain

That thy dear blood was poured in vain!’

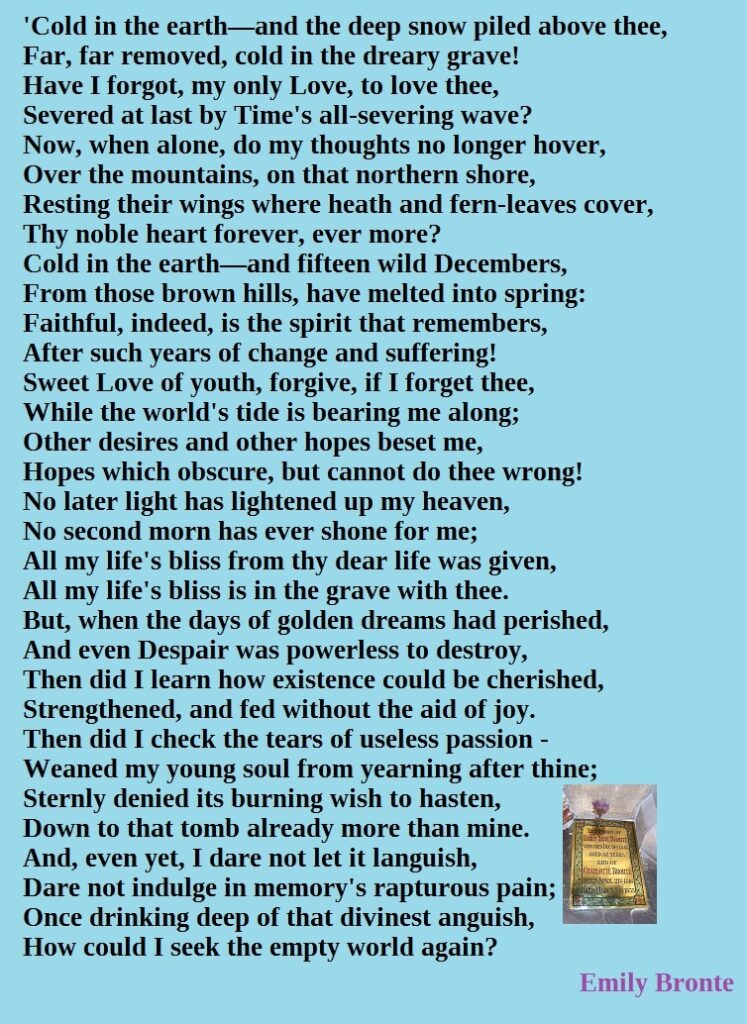

This poem also features the words ‘cold as the earth’ which reminds us of the start of another poem dealing with the aftermath of death, the brilliant ‘Remembrance’ with its opening lines of:

‘Cold in the earth – and the deep snow piled above thee,

Far, far, removed, cold in the dreary grave!’

This poem is often considered one of Emily’s very best, alongside ‘No Coward Soul Is Mine’ – another poem which ponders the mystery of life, death, and what comes next. This then, especially when we also consider the mortality rate in Wuthering Heights, was a subject that clearly exercised Emily’s mind, but why, and what do her words reveal about her beliefs?

I think the most common view of Emily as a poet, and as a person, is that she was a gloomy, very serious person. Someone who lingered upon the notion of death just as John Keats did when he wrote: ‘I have been half in love with easeful Death/ Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme.’

Was Emily Brontë really like that? I don’t think so.

We hear from Ellen Nussey, as close to her as anyone outside her family, that Emily loved to play practical jokes and laugh out loud. We hear from family friend John Greenwood that Emily had a sweet voice and a lovely nature. We hear that long time servant Martha Brown loved Emily especially because ‘she was so kind’.

One reason that Emily wrote about death is because it was a dramatic denouement to her tales of Gondal. The two poems quoted above are both poems of Gondal, the imaginary kingdom which dominated so much of Emily’s creative output. The seminal Brontë biographer Juliet Barker also places ‘Death’ as a Gondal poem, and yet it was in the Honresfield manuscript. This book contained Emily’s private verse, poems which were not set in Gondal and which were kept secret even from elder sister Charlotte until her accidental discovery of them set the Brontë publishing venture in full motion. It seems to me then that the following poem is not set in Gondal at all, but was something very personal to Emily.

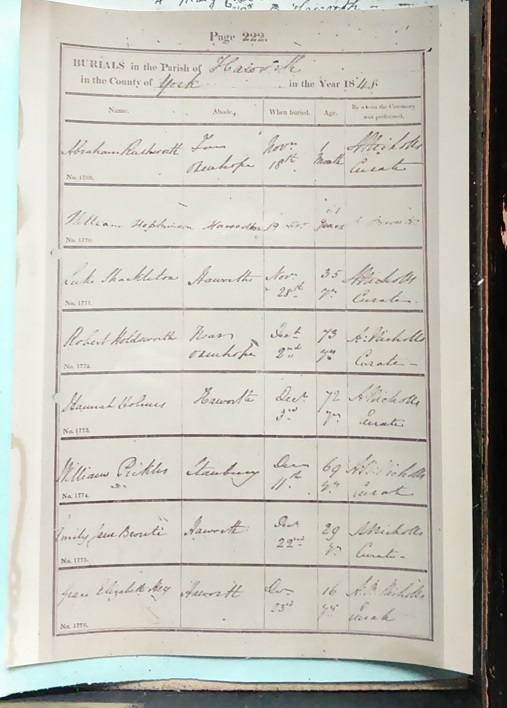

Death touched the lives of all the young Brontës to an extent, although Anne’s youth perhaps saved her from too sharp a memory of the loss of her elder sisters Maria and Elizabeth, and meant that she would have had no recollection of the mother who died when she was just one. Emily was two years older, however, and she had been at the Cowan Bridge school which sealed the fates of Maria and Elizabeth.

Emily Brontë was approaching her seventh birthday when her two eldest sisters died of tuberculosis, but she was a brilliant, precocious child and this tragedy stayed with her forever. She pondered deeply on the nature of life and death for the rest of her life, but this wasn’t a morbid study for her because she became convinced that death was not the end.

We see this in all her poetic musings on death, and in the closing scene of her only novel. Emily believed that whilst graves contained mortal remains it was vain to weep over them because the spirit lived on. In what form she believed it to live on is open to interpretation. Certainly her poems show a belief in an everlasting spirit and in a deity, but it doesn’t necessarily align with orthodox Christian belief. Perhaps Emily, so attuned with the natural world and its constant cycle of birth, death and rebirth, believed in rebirth of the human spirit too, a belief in reincarnation that is hinted at in some of her greatest work?

As with so much of the very best literature, the reader is left to place their own interpretation on it. I leave you now with this poem written 177 years ago today, and I hope you can join me again next week for another new Brontë blog post.

‘Death! that struck when I was most confiding.

In my certain faith of joy to be –

Strike again, Time’s withered branch dividing

From the fresh root of Eternity!

Leaves, upon Time’s branch, were growing brightly,

Full of sap, and full of silver dew;

Birds beneath its shelter gathered nightly;

Daily round its flowers the wild bees flew.

Sorrow passed, and plucked the golden blossom;

Guilt stripped off the foliage in its pride

But, within its parent’s kindly bosom,

Flowed for ever Life’s restoring tide.

Little mourned I for the parted gladness,

For the vacant nest and silent song –

Hope was there, and laughed me out of sadness;

Whispering, “Winter will not linger long!”

And, behold! with tenfold increase blessing,

Spring adorned the beauty-burdened spray;

Wind and rain and fervent heat, caressing,

Lavished glory on that second May!

High it rose – no winged grief could sweep it;

Sin was scared to distance with its shine;

Love, and its own life, had power to keep it

From all wrong – from every blight but thine!

Cruel Death! The young leaves droop and languish;

Evening’s gentle air may still restore –

No! the morning sunshine mocks my anguish –

Time, for me, must never blossom more!

Strike it down, that other boughs may flourish

Where that perished sapling used to be;

Thus, at least, its mouldering corpse will nourish

That from which it sprung – Eternity.’