Do you remember how old you were when you first discovered a Brontë novel? Quite possibly it was Jane Eyre, a book which has captivated readers of all ages for well over 170 years now. Despite other great works to her name it remains Jane Eyre which has made its author a literary legend across the world, but at the time of its publication the author remained purposefully secluded. In today’s post we’re going to look at the discovery of Jane Eyre in the local area, and the author’s response to that discovery.

Jane Eyre was published by Smith, Elder & Co on 16th October 1847, with the subtitle ‘An Autobiography’. The author, as far as the world and the publisher knew, was a mysterious Currer Bell, who had previously written a book of poetry with his brothers Ellis and Acton Bell. Of course, we know that Currer Bell was a pseudonym of Charlotte Brontë, but this fact was kept hidden, even from those closest to her, for a long time.

Other than Emily and Anne, who were also involved in this pseudonymous publishing venture, who did Charlotte confide in? We know that Branwell Brontë was kept out of the loop, as Charlotte wrote: ‘My unhappy brother never knew what his sisters had done in literature – he was not aware that they had ever published a line.’

Surely, however, Charlotte would have told her best friend Ellen Nussey that she was the author of a hugely successful novel, or surely Ellen would have known this anyway, as we know that Charlotte corrected proofs of Jane Eyre whilst she was a guest in the Nussey house at Brookroyd? It seems not.

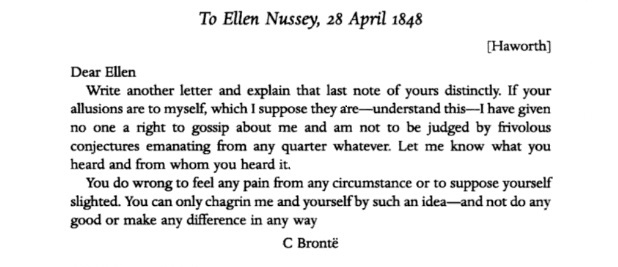

In late April 1848 Charlotte received a letter from Ellen Nussey; unfortunately no copy of this letter remains but we can guess its subject matter from this angry reply that Charlotte sent on 28th April 1848:

Ellen has heard rumours about Charlotte that has left her feeling hurt (or ‘chagrined’ as Charlotte rather wonderfully puts it), and we get further clues as to the nature of these rumours in a further letter sent from Charlotte to Ellen on 3rd May 1848 (once again we don’t have Ellen’s letter that this is in reply to):

Now we see without any doubt that Ellen Nussey has heard a report that Charlotte Brontë was in fact Currer Bell, author of Jane Eyre. Nearly seven months after its publication Charlotte had kept this hidden from her best friend, but nothing could stop the rumours that were now circulating in the polite society of Birstall and Gomersal where she lived.

Charlotte could hardly be stronger in her denial. She has not written any books, and if anyone says that she has they are no friend of hers. In a conciliatory touch at the foot of the letter Charlotte says that she remains faithfully Ellen’s, even though she has calumniated her.

This makes me think that Charlotte Brontë would have made a good politician, so forceful is her denial of something that she knew to be true. Before we look at why she did this, let’s ponder on how the ‘Birstalians’ and ‘Gomersalians’ came to realise the true identity of Currer Bell.

Jane Eyre was an overnight success and it was rapidly read across the country by those who were literate and wealthy enough to be book readers. It’s no surprise then that it was read widely in the West Riding of Yorkshire where Ellen Nussey, and the Brontës themselves, lived. Despite its subtitle the novel is not remotely as autobiographical as another book about life as a governess, Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë, and yet there was one clue within it which continued to be problematic, both for the author and for her later biographer Elizabeth Gaskell: Jane’s sojourn at Lowood School.

The portion of the novel dealing with this cruel, deadly school and the death of schoolgirls within it, including Jane’s best friend Helen Burns, resonated deeply with certain of its readers. There were many in the area who knew the story of Patrick Brontë, the curate of Haworth, who lost two of his daughters to consumption caught at Cowan Bridge school. Helen Burns was closely modelled on Maria Brontë, whose anniversary of her death aged 11 occurred this week, and so those who knew Maria’s tragic tale began to speculate that the author must have known of it too.

Speculation then turned to the eldest surviving daughter of Reverend Patrick Brontë. She was known for her intelligence and her bookish nature, and she herself had been a pupil at Cowan Bridge School and had to watch her sister Maria catch consumption and then die of it. That was why the depiction of Lowood was such a powerful one, such an angry one. The more the local readership pondered on it, the more it made sense: the celebrated author Currer Bell must in fact be the unassuming curate’s daughter Charlotte Brontë!

As it was well known that Ellen Nussey was Charlotte’s best friend people began to ask her to confirm or deny the rumours. Surely at first she would have denied the rumours, thinking it impossible that Charlotte had written this great book without telling her. As the rumours gathered in force and number, however, even Ellen must have suspected they were true, which must have been a devastating moment for her and which then led to her letters of April and May 1848.

We have looked before at why the Brontës chose to use pen names, and the pen names of Bell in particular. Emily Brontë in particular, an intensely shy genius, was vehemently opposed to their true identities ever being revealed. Charlotte Brontë had promised her that she would never reveal her identity as Currer Bell, and so steadfastly did she keep this promise that even Ellen Nussey was kept in the dark.

Eventually, of course, the truth could be kept hidden no longer and Ellen was finally told that Charlotte was an author. Doubtless she too was told the reason for the secrecy, of the vow she had made to Emily and her own wish for privacy at all costs; apologies would have been made and accepted. Nobody had been told that Currer Bell was Charlotte Brontë; except, that wouldn’t have been true either.

Charlotte had in fact revealed the truth to her other great friend, Mary Taylor. Indeed, she even sent an early copy of Jane Eyre to Mary in New Zealand as we know from a letter which Mary sent back to Charlotte. Perhaps Charlotte was so excited that she simply had to tell someone. She chose Mary rather than Ellen because of the distance between them, and the safety that implied, but also perhaps she valued Mary’s intellect whereas she said of Ellen, ‘Ellen is without romance – if she attempts to read poetry or poetic prose aloud I am irritated and deprive her of the book; if she talks of it I stop my ears.’

If Ellen had known that, she really would have been chagrined!

Thank you for all your kind words after last week’s post. Well over a week later I’m still testing positive for Covid, but I’m plodding on. I hope you are all happy and healthy, and I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Yes I remember when I first read Jane Eyre. I was fifteen. I can picture the smallish paperback. I remember the store: a drugstore, at the time there were few chain bookstores, and no good bookstore in the area I lived in. I read it riveted, and then read and reread it.

I’m really sorry to see that you are still testing positive for this wretched disease. Your blog posts bring me a great deal of pleasure. I hope you will soon be feeling well again. I wish people would realise Covid hasn’t gone. Both of our daughters work in a local hospital and the eldest, who has worked there for years, says the infection rate is far worse now than it was in the first wave of the pandemic.