Jubilee fever has gripped the United Kingdom this weekend, as large swathes of the nation celebrate Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s seventy years on the throne! A remarkable achievement, and a remarkable record of duty and loyalty from our monarch. Duty and loyalty were also hugely important to the Brontë sisters of course, and in today’s post we’re going to look at royalty in the Brontë lives and writing.

The Brontës are classed, quite rightly, as some of the greatest writers of the Victorian period, but Victoria wasn’t on the throne at the time of their birth. In fact, the Brontë siblings were all born in the reign of George III, the longest serving King of Great Britain. Mostly known today for his bouts of ‘madness’, probably caused by porphyria, he reigned for sixty years, although his reign also saw his son George take official, yet temporary, control of the kingdom in what became known as ‘the Regency’.

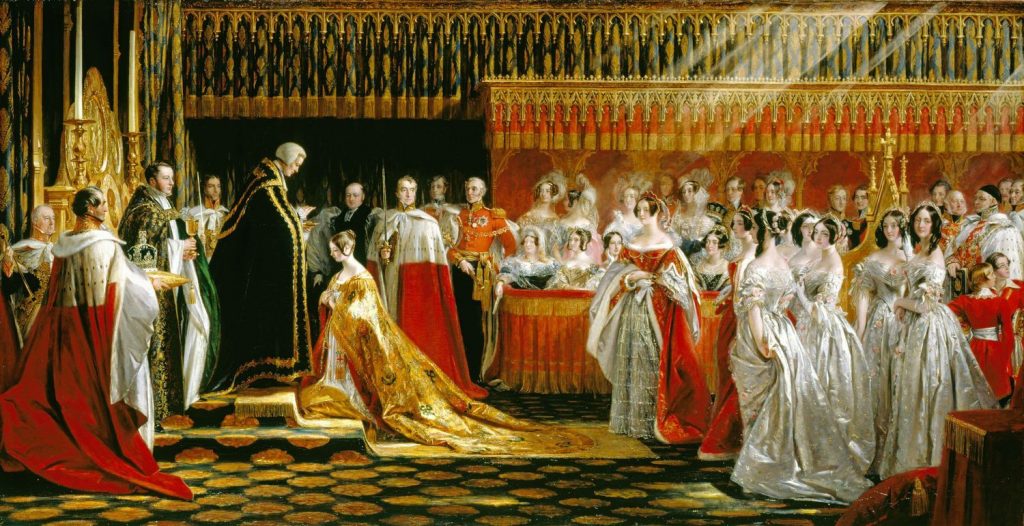

George III was our longest serving King, but of course we have two Queens who surpassed him. Our very own Elizabeth II is the first monarch to enjoy a platinum jubilee, after which we come to Queen Victoria who reigned for nearly 64 years from 1837 to 1901. It was Victoria, then, who dominated the adult lives of the Brontës, and the century they lived in. We’ll soon see what the Brontës thought of their queen, but what did she think of them?

Queen Victoria (named Lady Alexandrina Victoria at the time) was born in May 1819, making her three years younger than Charlotte Brontë, a year younger than Emily Brontë, and eight months older than Anne Brontë. Victoria was an avid reader, and from her diaries we know that one book which particularly caught her attention was Jane Eyre, which she called ‘that melancholy, interesting book.’ On May 21st 1858, Victoria wrote of Charlotte’s novel: ‘We remained up reading ‘Jane Eyre’ til half past 11. Quite creepy from the awful account of what happened the night before the marriage, which was interrupted in the church.’

This could be the famous ‘royal we’ in action, or it could be that the Queen was reading Jane Eyre to her beloved husband Prince Albert (as she herself said she was doing in an earlier diary entry. If so, perhaps they were thinking of their own wedding at St. James’ Palace 18 years earlier as they read of Jane’s impending nuptials – little wonder that the sudden cessation of the ceremony had them gripped, just as it had with so many of their subjects.

It may be that the royal couple were reading other books at the same time, for it was on August 4th that Queen Victoria neared the end of the novel, writing: ‘At near 10 we went below and nearly finished reading that most interesting book Jane Eyre. A peaceful, happy evening.’ The Queen returned to Charlotte’s novel in very different circumstances in 1880. By then she had been mourning her husband for nearly two decades, but she still found solace in this great book. On November 23rd of that year, her diary entry reads: ‘Finished Jane Eyre, which is really a wonderful book, very peculiar in parts, but so powerfully and admirably written, such a fine tone in it, such fine religious feeling, and such beautiful writings. The description of the mysterious maniac’s nightly appearances awfully thrilling. Mr Rochester’s character a very remarkable one, and Jane Eyre’s herself a beautiful one. The end is very touching, when Jane Eyre returns to him and finds him blind, with one hand gone from injuries during the fire in his house, which was caused by his mad wife.’

Queen Victoria was a fan of Charlotte Brontë, at least, and it seems that the admiration was reciprocated: the young Brontës even named one of their pet geese after her. We also hear of their interest in Victoria’s pending coronation in the 1837 diary paper of Emily and Anne Brontë: ‘Tabby in the kitchin – the Emprerors and Empresses of Gondal and Gaaldine preparing to depart from Gaaldine to Gondal for the coranation which will be on the 12th of July. Queen Victoria ascended the throne this month.’

The real world Victoria had already inspired a fictional queen in the Brontë writing, and this wouldn’t be the last occasion. Charlotte herself saw Queen Victoria in 1843, whilst she was in Brussels, as she recorded in a letter to Emily Brontë:

‘You ask about Queen Victoria’s visit to Brussels. I saw for her an instant flashing through the Rue Royale in a carriage and six, surrounded by soldiers. She was laughing and talking very gaily. She looked a little stout, vivacious lady, very plainly dressed, not much dignity or pretension about her. The Belgians liked her very much on the whole. They say she enlivened the sombre court of King Leopold, which is usually as gloomy as a conventicle.’

Like so much of Charlotte’s sojourn in the Belgian capital it later influenced another of her brilliant novels: Villette. Surely we can see Charlotte’s memories of the Queen of England in Lucy Snowe’s impressions upon meeting the Queen of Labassecour?

‘A signal was given, the doors rolled back, the assembly stood up, the orchestra burst out, and, to the welcome of a choral burst, enter the King, the Queen, the Court of Labassecour.

Till then, I had never set eyes on living king or queen; it may consequently be conjectured how I strained my powers of vision to take in these specimens of European royalty. By whomsoever majesty is beheld for the first time, there will always be experienced a vague surprise bordering on disappointment, that the same does not appear seated, en permanence, on a throne, bonneted with a crown, and furnished, as to the hand, with a sceptre. Looking out for a king and queen, and seeing only a middle-aged soldier and a rather young lady, I felt half cheated, half pleased.

Well do I recall that King – a man of fifty, a little bowed, a little grey: there was no face in all that assembly which resembled his. I had never read, never been told anything of his nature or his habits; and at first the strong hieroglyphics graven as with iron stylet on his brow, round his eyes, beside his mouth, puzzled and baffled instinct. Ere long, however, if I did not know, at least I felt, the meaning of those characters written without hand. There sat a silent sufferer – a nervous, melancholy man. Those eyes had looked on the visits of a certain ghost – had long waited the comings and goings of that strangest spectre, Hypochondria. Perhaps he saw her now on that stage, over against him, amidst all that brilliant throng. Hypochondria has that wont, to rise in the midst of thousands – dark as Doom, pale as Malady, and well-nigh strong as Death. Her comrade and victim thinks to be happy one moment – “Not so,” says she; “I come.” And she freezes the blood in his heart, and beclouds the light in his eye.

Some might say it was the foreign crown pressing the King’s brows which bent them to that peculiar and painful fold; some might quote the effects of early bereavement. Something there might be of both these; but these are embittered by that darkest foe of humanity – constitutional melancholy. The Queen, his wife, knew this: it seemed to me, the reflection of her husband’s grief lay, a subduing shadow, on her own benignant face. A mild, thoughtful, graceful woman that princess seemed; not beautiful, not at all like the women of solid charms and marble feelings described a page or two since. Hers was a somewhat slender shape; her features, though distinguished enough, were too suggestive of reigning dynasties and royal lines to give unqualified pleasure. The expression clothing that profile was agreeable in the present instance; but you could not avoid connecting it with remembered effigies, where similar lines appeared, under phase ignoble; feeble, or sensual, or cunning, as the case might be. The Queen’s eye, however, was her own; and pity, goodness, sweet sympathy, blessed it with divinest light. She moved no sovereign, but a lady – kind, loving, elegant.’

Whether Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth has read a Brontë book or two we simply do not know, but we know that her sister did. In 1997, Princess Margaret visited Bradford, and became the first member of the Royal Family to visit the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth. Here’s an account of her visit from the Bradford Telegraph and Argus:

The Princess spent some time reading Jane Eyre in silence: it can have that effect on all of us. The Platinum Jubilee celebrations are drawing to our end, but our celebration of the lives and works of the Brontë sisters of Haworth will never end. I hope you can join me again next week for another new Brontë blog post.

What a lovely post. From what I’ve read of the sisters and Queen Victoria is that they all simply adored her. Happy Jubilee celebrations!

Thank you so much Jen!

Having just returned from an enlightening tour of the UK during the 70th Platinum Jubilee of Her Majesty Elizabeth II and visited Haworth and all the Bronte country I could find, I thoroughly enjoyed this peek into the Bontes and royalty. Thanks for providing these insights on the connections between them.