It’s that time of year again when things go bump in the night! The clocks have gone back, the evenings are darker, and we can never be sure where that shadow came from or what that rustling noise is! That can mean only one thing: it’s time for another Halloween weekend Brontë blog post.

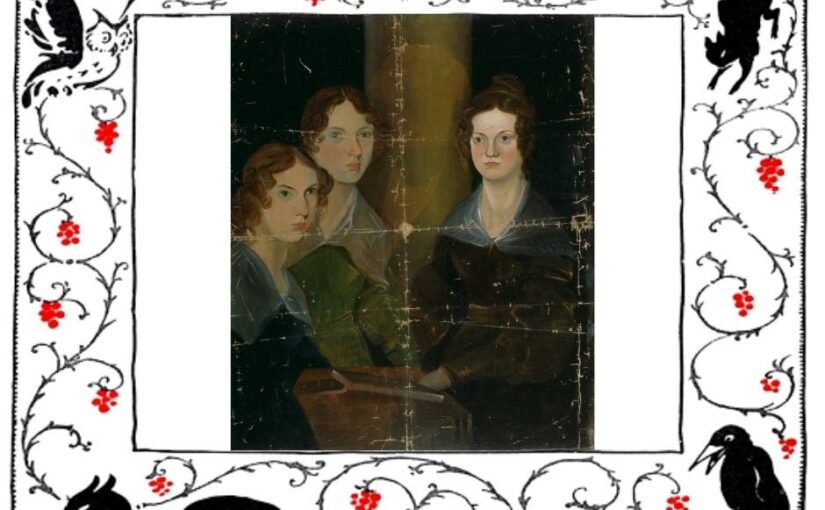

The Brontë sisters loved the world of the supernatural, as is especially evident in the novels of both Emily and Charlotte Brontë. Perhaps this love came from stories they heard as children from loyal servant Tabby Aykroyd and from their Aunt Branwell, which shows how important sharing stories and folk tales with children really is? It fired up their incredible imaginations and powers of creativity which eventually found outlet in the novels we love today, but some say that spooky encounters aren’t solely limited to their novels – after all, there have been reported sightings of the ghosts of all three writing Brontë sisters, and not always in the places you might expect!

Let us begin with the reported ghost of Emily Brontë, as her spectre is the only one said to appear in the place forever associated with the Brontës – Haworth.

In the early nineteenth century, weaving was the main employment of the Haworth workforce. Eventually large factories and machine driven looms dominated the area and the West Riding of Yorkshire as a whole, but hand loom weavers could still be found who followed the old traditions of warp and weft. A line of old weaver’s cottages can still be seen in Haworth today on West Lane not far from the parsonage itself; dating from the mid-eighteenth century they would have been well known to the Brontë siblings, and on occasion may have been visited by them if they were accompanying their father on parochial visits.

One such cottage, beautiful and evocative, is now Weaver’s Guesthouse, although it has formerly been Weaver’s Restaurant and a Toby Jug restaurant. What stories it could tell. What stories it possibly continues to tell?

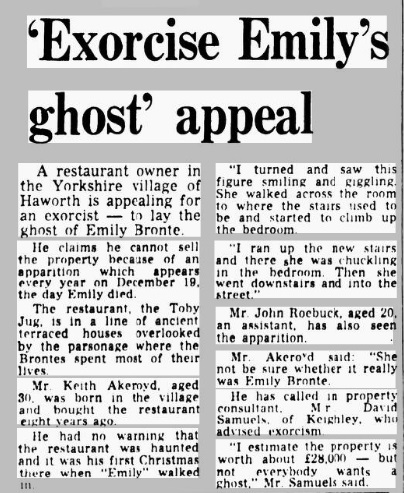

For much of the twentieth century there were reports of a ghostly lady making a regular appearance. This grey lady was always dressed in a long grey dress with a bonnet and shawl, and carrying a basket on her arm as if she was making a visit. In 1974 Keith Akeroyd, owner of the Toby Jug restaurant in the old weaver’s cottage, described one of the visitations, and made an appeal for an exorcism, as reported by the Birmingham Daily Post on 30th September 1974:

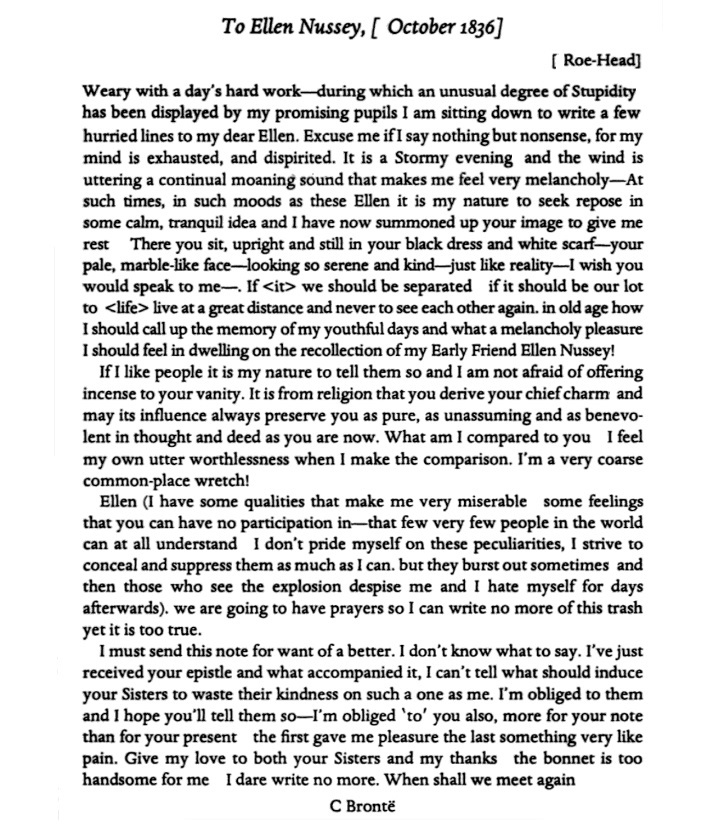

Here we see in print the name that Haworth locals had long given the grey lady: Emily Brontë! It is said that the ghost appears annually on 19th December, the anniversary of Emily’s tragic passing. Could this really be Emily Brontë’s ghost? Further descriptions always describe the grey lady as laughing and giggling; this is not how we usually think of Emily Brontë today, but in fact a letter from Ellen Nussey to Elizabeth Gaskell describes how Emily loved to play practical jokes and then laugh uproariously. Could this be a practical joke that she continues to play on the people of Haworth, 174 years after her passing?

Emily was the most home loving of the Brontës (despite a brief spell as a teacher in Halifax and then as a student in Brussels), so perhaps it’s understandable that people associate her ghost with Haworth, but the ghost of Charlotte Brontë hit the headlines when causing a commotion in a village 50 miles to the south: Hathersage.

Hathersage was a place that Charlotte knew well. She had stayed in the village parsonage for a month in the summer of 1845 in the company of Ellen Nussey, whose brother Henry Nussey had been made vicar there. This was a pivotal moment in the Brontë story, as it was in Haworth that Charlotte met the Eyre family of North Lees Hall, and the beautiful Peak District village itself became the Morton of her novel Jane Eyre.

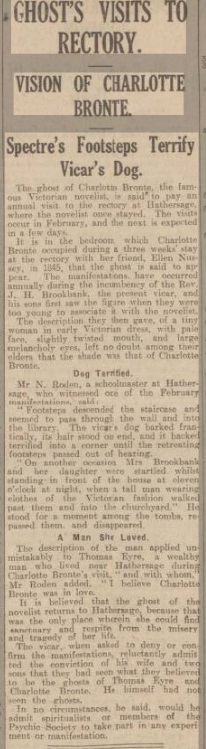

As visitors to the village will soon see, it’s understandable why Charlotte Brontë should have loved Hathersage, but did she love it and its vicarage so much that she never wanted to leave? In February 1927 local newspapers reported a strange sighting:

It is reported here that Charlotte’s ghost has been appearing on an annual basis at the beautiful Hathersage Parsonage she had known and loved. The incumbent vicar’s children, it is reported, often see her ghost, and her appearance is said to terrify the dog. The article also conjectures that her phantom returns to this spot because she was in love with the man who lived there, Reverend Henry Nussey whose proposal she rejected and who at least partially inspired St. John Rivers in Jane Eyre, and because she had found calm at Hathersage in contrast to the misery of Haworth. The article also points out that the ghost of Thomas Eyre, who had lived at nearby North Lees Hall, also haunted the building and that the Psychic Society had offered to help investigate the matter, but their request was not being entertained.

A month later, however, Hathersage’s vicar the Reverend J. H. Brookbank took to the press to deny these claims, saying that the idea that he and his family had seen Charlotte’s ghost was absurd – but perhaps it’s telling that there was no comment from the family dog!

So, if Emily Brontë’s ghost is said to appear in Haworth and Charlotte Brontë’s ghost is said to walk in Hathersage, where would Anne Brontë’s ghost be found? Why, in Long Island, New York of course!

Anne Brontë’s first job was as a governess at Blake Hall, Mirfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Once again it was a pivotal moment in the Brontë story, as her experiences of life with the Ingham family there inspired the first half of her début novel Agnes Grey – where the Inghams were portrayed as the horrific Bloomfields.

Anne left her employment at Blake Hall in late 1839, but the Hall remained an imposing presence in Mirfield until the 1950s when it was demolished to make way for a new housing estate, with its once exalted fixtures and fittings sold off piece by piece in auctions that attracted bidders from across the world. Perhaps the architectural highlight of the hall was its grand central staircase, and this was bought by a man named Allen Topping of Long Island, New York. Topping was fabulously wealthy with money no object (think of him as a real life ‘Jay Gatsby’), so he paid for the Blake Hall staircase to be dismantled, shipped to America and then reassembled in his own mansion.

In 1962 Allen’s widow reported seeing a ghostly lady descend the staircase dressed in Victorian garb including a long shawl. Mrs Toppings’ dog started barking but when she comforted the dog, the figure smiled at her. This spectral figure was then seen on a number of occasions, and Mrs Topping sensed that it was the ghost of Anne Brontë!

So, what’s the main lesson we’ve learned from these spooky tales of Brontë hauntings? If you have a dog and you hear it barking at thin air on the 31st October climb swiftly under your duvet and do not, I repeat do not, look at what’s caught their attention!

This has been a bit of fun, of course, so I leave it to you whether you believe in ghosts in general, and the ghosts of the Brontës in particular. On a serious note, however, we also remember at this time of year Elizabeth Branwell. As mentioned earlier, Elizabeth’s Cornish folk tales helped shape the Brontë imagination at a formative age. She travelled to Haworth in 1821 when her sister Maria was on her deathbed, and could have returned to the warmth and wealth she was used to in Penzance, 400 miles to the south, after a suitable period of mourning had been observed.

Elizabeth Branwell was not one to shirk her duty, however, and she refused to turn her back on the young nephew and nieces who had so suddenly been left without their mother. Leaving her beloved Cornwall behind forever, Elizabeth Branwell became Aunt Branwell and remained in Haworth Parsonage until her own death 21 years later. She became a second mother to the Brontës, and without her love, support and legacy (quite literally, as it was money left in her will that allowed the publication of the first Brontë books) there would be no Brontë novels today. Well done Elizabeth Branwell!

Halloween is a time for celebrating with loved ones, and it’s a time for indulging in spooky stories – and if you’re looking for Brontë related chills I highly recommend The Brontës: Afterlife, a fabulous new collection of Brontë related short stories with a hint of the macabre!

I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post, and if you do happen to see a grey lady when you turn out the lights don’t be too scared – it might only be Emily enjoying herself!