Everyone of discernment has a favourite Brontë novel. For me it is Emily’s Wuthering Heights, and I also think its companion piece Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë (the two books were published side by side in 1847) is the most underrated book of all time. All Brontë books are wonderful, but of course we wish there could have been many more of them. Only Charlotte Brontë left us a significant number to choose from, and even she only wrote four completed novels. The choice of favourite Charlotte Brontë novel is a difficult one, but many people would choose Villette – a novel completed exactly 170 years ago today. In today’s new post we’re going to look at the stormy passage of the genesis of Villette.

Firstly, apologies to anyone who thinks I put too much of Charlotte Brontë into this blog. I had rather an angry message from a reader who complained that the blog was called Anne Brontë but that Charlotte was featured too prominently, so they felt I was diminishing Anne and they were unsubscribing. Anne Brontë is my favourite writer, but I love the Brontë family as a whole, and I think the history of the whole family is vital if we’re to understand Anne – added to which, of course, Charlotte lived longer, wrote more, and left us much more documentary evidence in the form of her letters. So, I hope, dear reader, that you will excuse me if Charlotte continues to be central to blog posts such as this one.

If you’re still here then hopefully you have accepted my apology. By the time of Villette, Charlotte’s life had changed immeasurably since the time when she wrote The Professor and then Jane Eyre. Charlotte Brontë, or Currer Bell as the reading public still knew her, was by now an established author and her financial situation had vastly improved. Above all else, however, Charlotte was lonely. She had composed her early novels with beloved sisters Emily and Anne alongside her, walking around their dining table together in the evening candlelight, discussing ideas and plot lines. Now, Emily and Anne were dead, and loyal servant Martha Brown revealed to a parsonage visitor :

‘For as long as I can remember Miss Brontë [Charlotte], Miss Emily and Miss Anne used to put away their sewing after prayers and walk all three one after the other round the table in the parlour till near eleven o’ clock. Miss Emily walked as long as she could, and when she died Miss Anne and Miss Brontë took it up – and now my heart aches to hear Miss Brontë walking, walking, on alone.’

The grief Charlotte suffered from at the time of the writing of Villette understandably impacted upon its genesis and upon its content. It is a wonderful novel that grows deeper and deeper page by page, and with an atmosphere uniquely its own that stays with you long after its stormy end.

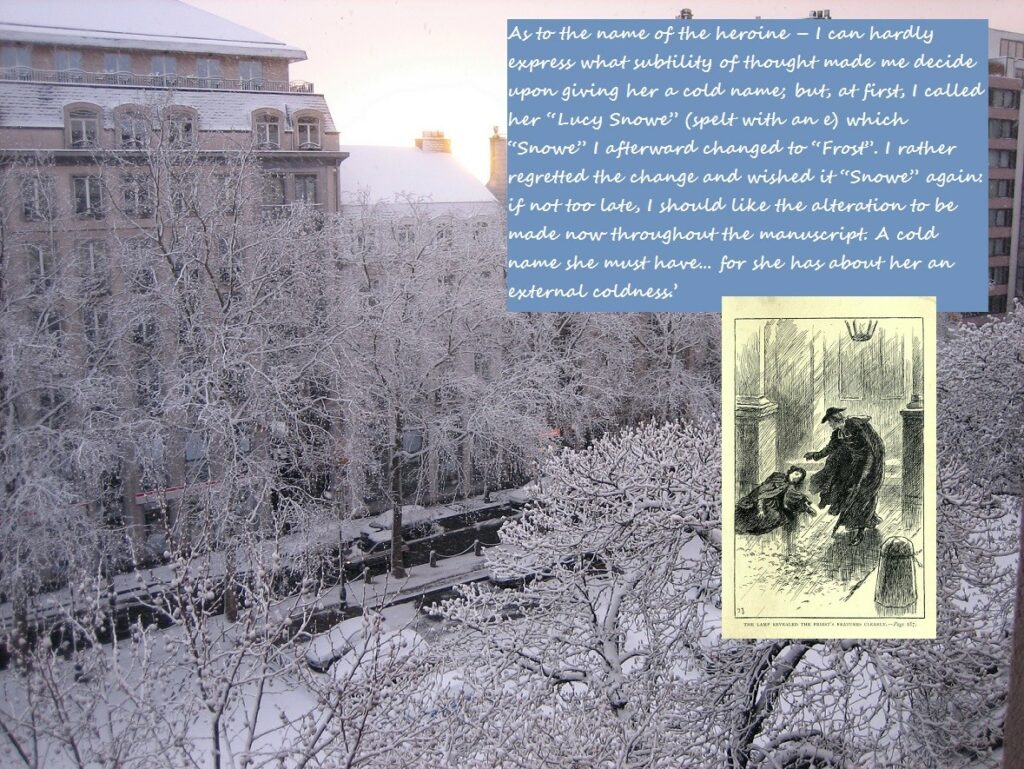

Indeed the word stormy is a perfect way to describe the novel and its creation, just as the name Lucy Snowe was perfectly chosen for its protagonist – although Charlotte revealed how she had been called Lucy Frost at the time that the draft was submitted.

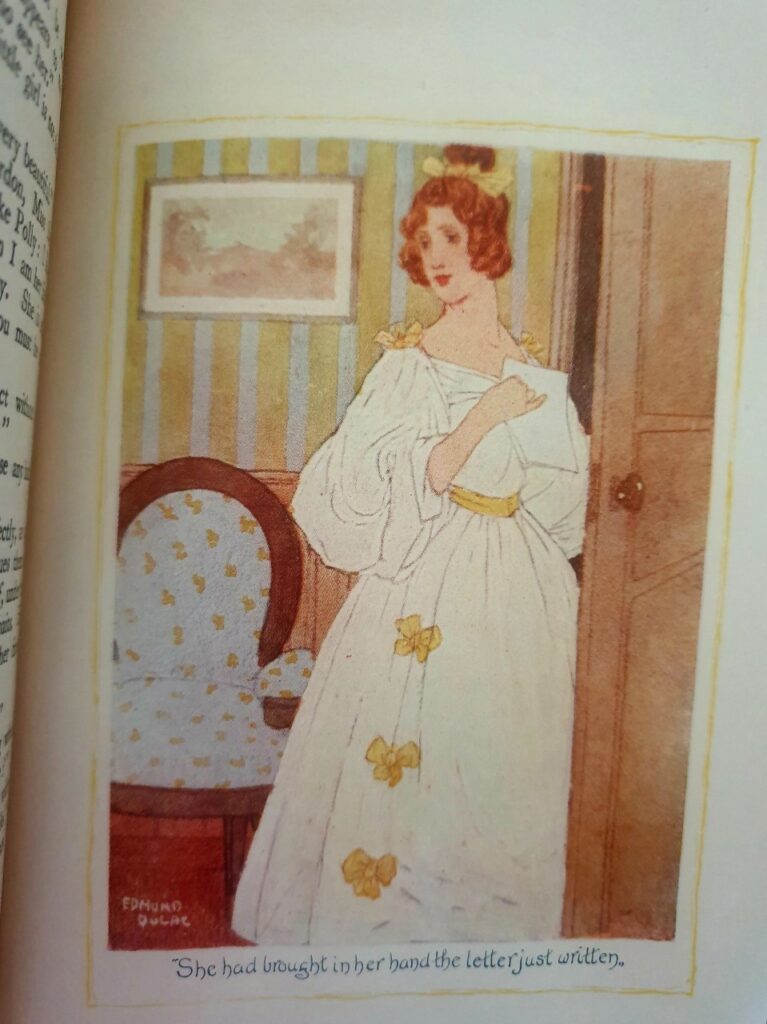

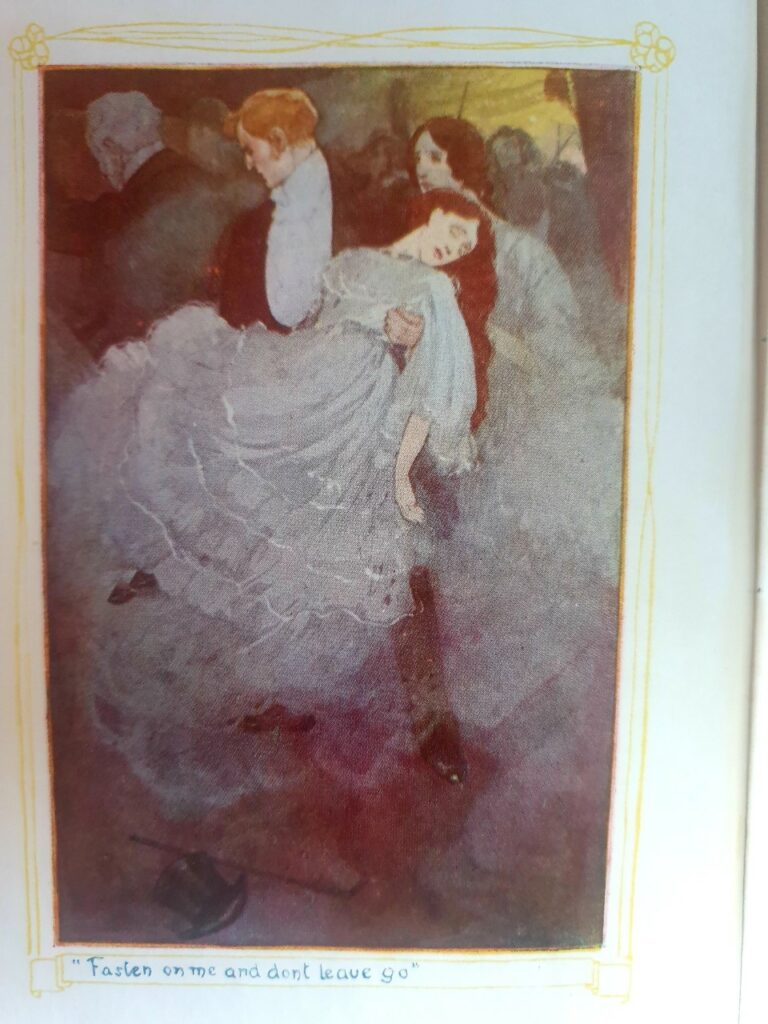

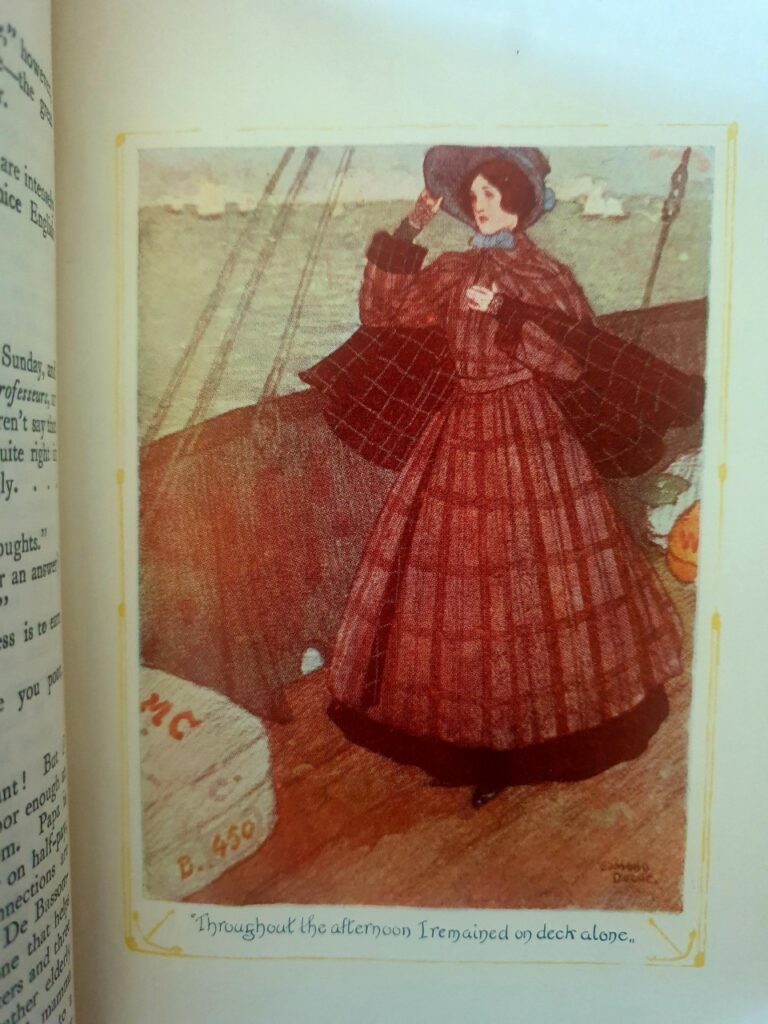

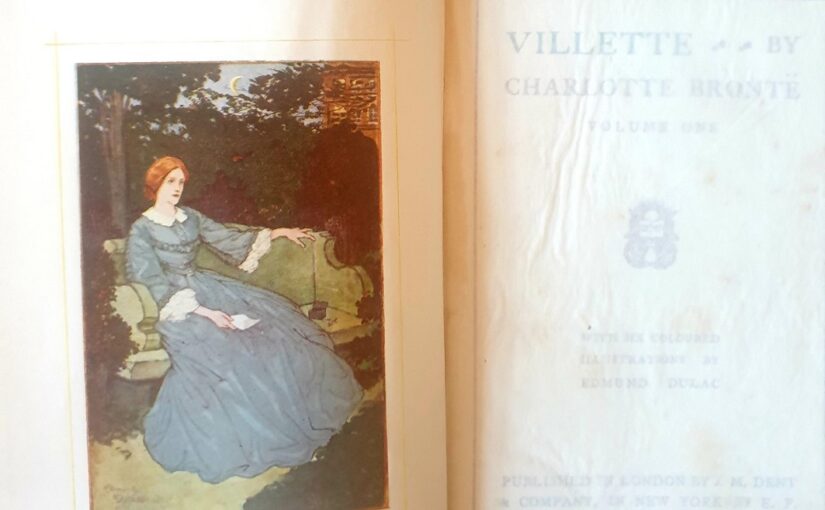

The writing of Villette was a long, drawn out, tortuous process for Charlotte Brontë – one in which long periods of inactivity followed or preceded rapid bursts of composition. Three years had gone by since Shirley had been published, three years during which her publishers Smith, Elder and Co must have longed for a new novel to build on the reputation ‘Currer Bell’ had earned with the reading public, but it was not until 1852 that Villette finally began, slowly, slowly to take shape. (Incidentally, you will see illustrations for Villette drawn by the great Edmund Dulac throughout this post, including in the header above).

On 12th March 1852 Charlotte wrote to her friend and former teacher than employer Margaret Wooler: ‘For nearly four months now (i.e. since I first became ill) I have not put pen to paper – my work has been lying untouched and my faculties have been rusting for want of exercise; further relaxation is out of the question and I will not permit myself to think of it. My publisher groans over my long delays; I am sometimes provoked to check the expression of his impatience with short and crusty answers.’

By April 1852 Charlotte wrote to Laetitia Wheelwright to express her state of mind at this time: ‘I struggled through the winter and the early part of the spring often with great difficulty. My friend [Ellen Nussey] stayed with me a few days in the early part of January – she could not be spared longer; I was better during her visit – but had a relapse soon after she left me which reduced my strength very much. It cannot be denied that the solitude of my position fearfully aggravated its other evils. Some long, stormy days and nights there were when I felt such a craving for support and companionship as I cannot express. Sleepless – I lay awake night after night – weak and unable to occupy myself – sat in my chair day after day – the saddest memories my only company. It was a time I shall never forget – but God sent it and it must have been for the best.’

Perhaps inevitably, this deep depression, this profound loneliness and longing for the company of those who were gone, found itself into Villette, as we see, for example, in chapter fifteen:

‘Indeed there was no way to keep well under the circumstances. At last a day and night of peculiarly agonizing depression were succeeded by physical illness, I took perforce to my bed. About this time the Indian summer closed and the equinoctial storms began; and for nine dark and wet days, of which the hours rushed on all turbulent, deaf, dishevelled – bewildered with sounding hurricane – I lay in a strange fever of the nerves and blood. Sleep went quite away. I used to rise in the night, look round for her, beseech her earnestly to return. A rattle of the window, a cry of the blast only replied – Sleep never came!

I err. She came once, but in anger. Impatient of my importunity she brought with her an avenging dream. By the clock of St. Jean Baptiste, that dream remained scarce fifteen minutes – a brief space, but sufficing to wring my whole frame with unknown anguish; to confer a nameless experience that had the hue, the mien, the terror, the very tone of a visitation from eternity. Between twelve and one that night a cup was forced to my lips, black, strong, strange, drawn from no well, but filled up seething from a bottomless and boundless sea. Suffering, brewed in temporal or calculable measure, and mixed for mortal lips, tastes not as this suffering tasted. Having drank and woke, I thought all was over: the end come and past by. Trembling fearfully – as consciousness returned – ready to cry out on some fellow-creature to help me, only that I knew no fellow-creature was near enough to catch the wild summons – Goton in her far distant attic could not hear – I rose on my knees in bed. Some fearful hours went over me: indescribably was I torn, racked and oppressed in mind. Amidst the horrors of that dream I think the worst lay here. Methought the well-loved dead, who had loved me well in life, met me elsewhere, alienated: galled was my inmost spirit with an unutterable sense of despair about the future. Motive there was none why I should try to recover or wish to live; and yet quite unendurable was the pitiless and haughty voice in which Death challenged me to engage his unknown terrors.’

By July 1852 Charlotte’s novel was still not progressing, and she wrote to Ellen Nussey: ‘All is silent as the grave. Cornhill [where her publisher was based] is silent too: there has been bitter disappointment there at my having no work ready for this season. Ellen we must not rely upon our fellow-creatures – only on ourselves – and on Him who is above both us and they. My labours as you call them stand in abeyance and I cannot hurry them – I must take my own time -however long that time may be.’

By October 1852, however, progress was being made rapidly – and it is clear that it is the great mutual love she shared with best friend Ellen, who has just stayed at Haworth Parsonage, which has enabled Charlotte to overcome the dark shadows which fell over much of this year:

‘Dear Nell, Your note came only this morning, I had expected it yesterday and was beginning actually to feel uneasy, like you. This won’t do, I am afraid of caring for you too much.

You must have come upon Hunsworth [home of Joe and Amelia Taylor] at an unfavourable moment; seen it under a cloud. Surely they are not always or often thus, or else married life is indeed but a slipshod paradise. I am glad, however, that the child is, as we conjectured, pretty well.

Miss Wooler’s note is indeed kind, good, and characteristic. I only send the ‘Examiner,’ not having yet read the ‘Leader.’ I was spared the remorse I feared. On Saturday I fell to business [the business of writing Villette], and as the welcome mood is still decently existent, and my eyes consequently excessively tired with scribbling, you must excuse a mere scrawl. You left your smart shoes. Papa was glad to hear you had got home well, as well as myself. Regards to all. Good-bye.— Yours faithfully, C. Bronte¨. I do miss my dear bed-fellow. No more of that calm sleep.’

By 30th October, Charlotte is preparing her publisher for the imminent arrival of her oft-delayed novel, and by 20th November the manuscript of the final volume was sent to George Smith, along with this letter:

‘My dear Sir, I send the 3rd. Vol. of ‘‘Villette’’ to-day, having been able to get on with the concluding chapters faster than I anticipated. When you shall have glanced over it – speak, as before, frankly.

I am afraid Mr. Williams [Smith’s assistant who had first discovered the genius of Jane Eyre was a little disheartened by the tranquillity of the 1st & 2nd. Vols.: he will scarcely approve the former part of the 3rd., but perhaps the close will suit him better. Writers cannot choose their own mood: with them it is not always high-tide, nor – thank Heaven! – always Storm. But then – the Public must have ‘‘excitement’’: the best of us can only say: ‘‘Such as I have, give I unto thee.’’

Glad am I to see that ‘‘Esmond’’ [by Thackeray] is likely to meet something like the appreciation it deserves. That was a genial notice in the ‘‘Spectator’’. That in the ‘‘Examiner’’ seemed to me not perhaps so genial, but more discriminating. I do not say that all the ‘‘Examiner’’ says is true – for instance the doubt it casts on the enduring character of Mr. Thackeray’s writings must be considered quite unwarranted – still the notice struck me as containing much truth. I wonder how the ‘‘Times’’ will treat ‘‘Esmond.’’

Now that ‘‘Villette’’ is out my hands – I mean to try to wait the result with calm. Conscience – if she be just – will not reproach me, for I have tried to do my best. Believe me, Yours sincerely, C. Brontë’

During the writing of this novel Charlotte suffered terribly from a depressive grief that frequently led to bouts of physical illness too. She felt alone and incapable of writing, but at the same time she was being urged to write by her publisher. As she says in her letter above, all she could do was try her best – and when we read Villette today we see that her best was very good indeed.

Villette is a deep, dark, brooding book which is as stormy as the time during which its author was writing it – it is a novel full of ghosts and memories, of tempests imagined and all too real, and it is a novel which is as deeply rewarding to read today as it was exactly 170 years ago when Charlotte placed her manuscript into an envelope and sent it on its way to London and the world. If you haven’t read Villette then I highly recommend it (and I highly wish there was a screen adaptation of the novel too), and I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Indeed it was an achievement, fighting her bereavements as she had to. She must have felt so alone. It is a very atmospheric novel and a triumph against adversity.

I personally like the balance between the Bronte family members.

Thank you Jennie!