With just two weeks until Christmas Day itself it’s time to ensure that the festive preparations are well under way. One lovely tradition that many still indulge is the making of Christmas cake – and of course you have to start those preparations early to ensure that it gets thoroughly doused in booze of one kind or another. As daughters of the village priest the Brontë siblings would have had to distribute this cake among parishioners, and here (from the rather lovely book The Brontës’ Christmas) is a traditional recipe from the time:

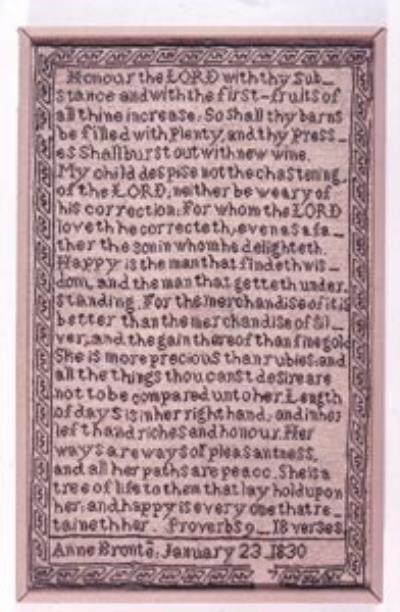

Our preparations here at annebronte.org involve lighting a second Advent candle today, so today’s Anne-vent offering is one of the very first pieces of ‘writing’ we have from Anne. It wasn’t created by pencil, quill or dip pen – it was created through the art of needlework. Here then is today’s candle – the sampler made by Anne Brontë to mark her tenth birthday.

Anne has handily dated it the 23rd of January 1830, meaning that she completed it six days after her milestone birthday, although she may have commenced her work on the big day itself. In case you don’t know what a sampler is, they were needlework creations designed to showcase the skill of the young person making it. They typically included a self-chosen quotation from the Bible, and often had the alphabet and numbers at the start or end, with an elaborate border around the perimeter.

Samplers like Anne’s were an important rite of passage for lower middle-class children like the Brontës. Working class children were faced with a life of danger and drudgery from an early age, whilst upper and upper-middle class children were prepared for a life of luxury and leadership from an early age. Girls who, like the Brontës, dwelt in the social strata between these extremes were destined for two possible careers: being a teacher or a governess, until such time as they became wives and mothers. It was essential therefore that they could sew and teach others to sew, so the sampler became a way to hone their skills and demonstrate it to others.

Anne, as we have seen before in this blog and in my books such as In Search Of Anne Brontë and Crave The Rose: Anne Brontë At 200 was the most successful Brontë in terms of employment. She was governess to the Robinson family of Thorp Green Hall for over five years, a term far longer than sisters Charlotte and Emily managed, and was much loved by the children in her care. She was also the most deeply devout of the Brontë siblings, so even by the age of ten she would have been very familiar with the scriptures. It is a beautiful choice that Anne has selected for her sampler, one of the most poetic sections of the Old Testament, and I particularly like: ‘She is more precious than rubies, and all the things thou canst desire are not to be compared unto her.’

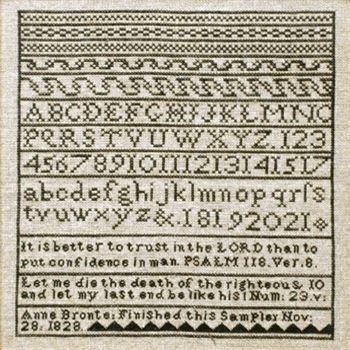

Samplers were created throughout a girl’s schooling, so let’s see a bonus sampler from Anne – this time an even earlier example, made by an eight year old Anne in November 1828. This is the very earliest thing created by Anne Brontë in existence today, and already we see a theme which will recur in The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall: ‘It is better to trust in the Lord than put confidence in man.’

Anne’s needlework is very impressive for an eight year old, especially by today’s standards of course, but there are a number of errors in this sampler? How many can you spot? (here’s a starter: Anne has missed 16 out and jumped from 15 to 17). By the sampler at the top of the post the errors had disappeared – Anne Brontë was never scared of hard work.

I leave you now with another beautiful poem by Anne. As we are looking at early work by the youngest Brontë, I present to you the very earliest extant poem by her: ‘Verses by Lady Geralda’, written by Anne when she was 16 years old and set in Gondal, the fictional land created by herself and Emily Brontë. It’s a suitably wintry poem, and it was written in December 1836. I hope to see you next week as we light our third Anne-vent candle with another new Brontë blog post.

“Why, when I hear the stormy breath

Of the wild winter wind

Rushing o’er the mountain heath,

Does sadness fill my mind?

For long ago I loved to lie

Upon the pathless moor,

To hear the wild wind rushing by

With never ceasing roar;

Its sound was music then to me;

Its wild and lofty voice

Made by heart beat exultingly

And my whole soul rejoice.

But now, how different is the sound?

It takes another tone,

And howls along the barren ground

With melancholy moan.

Why does the warm light of the sun

No longer cheer my eyes?

And why is all the beauty gone

From rosy morning skies?

Beneath this lone and dreary hill

There is a lovely vale;

The purling of a crystal rill,

The sighing of the gale,

The sweet voice of the singing bird,

The wind among the trees,

Are ever in that valley heard;

While every passing breeze

Is loaded with the pleasant scent

Of wild and lovely flowers.

To yonder vales I often went

To pass my evening hours.

Last evening when I wandered there

To soothe my weary heart,

Why did the unexpected tear

From my sad eyelid start?

Why did the trees, the buds, the stream

Sing forth so joylessly?

And why did all the valley seem

So sadly changed to me?

I plucked a primrose young and pale

That grew beneath a tree

And then I hastened from the vale

Silent and thoughtfully.

Soon I was near my lofty home,

But when I cast my eye

Upon that flower so fair and lone

Why did I heave a sigh?

I thought of taking it again

To the valley where it grew.

But soon I spurned that thought as vain

And weak and childish too.

And then I cast that flower away

To die and wither there;

But when I found it dead today

Why did I shed a tear?

O why are things so changed to me?

What gave me joy before

Now fills my heart with misery,

And nature smiles no more.

And why are all the beauties gone

From this my native hill?

Alas! my heart is changed alone:

Nature is constant still.

For when the heart is free from care,

Whatever meets the eye

Is bright, and every sound we hear

Is full of melody.

The sweetest strain, the wildest wind,

The murmur of a stream,

To the sad and weary mind

Like doleful death knells seem.

Father! thou hast long been dead,

Mother! thou art gone,

Brother! thou art far away,

And I am left alone.

Long before my mother died

I was sad and lone,

And when she departed too

Every joy was flown.

But the world’s before me now,

Why should I despair?

I will not spend my days in vain,

I will not linger here!

There is still a cherished hope

To cheer me on my way;

It is burning in my heart

With a feeble ray.

I will cheer the feeble spark

And raise it to a flame;

And it shall light me through the world,

And lead me on to fame.

I leave thee then, my childhood’s home,

For all thy joys are gone;

I leave thee through the world to roam

In search of fair renown,

From such a hopeless home to part

Is happiness to me,

For nought can charm my weary heart

Except activity.”