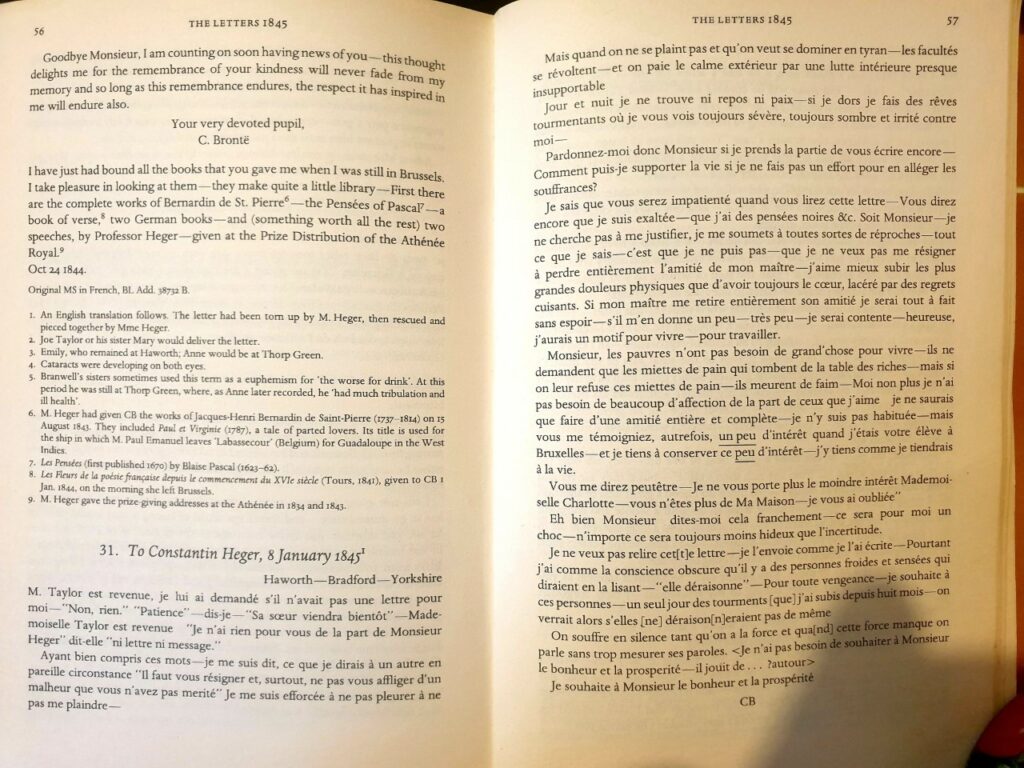

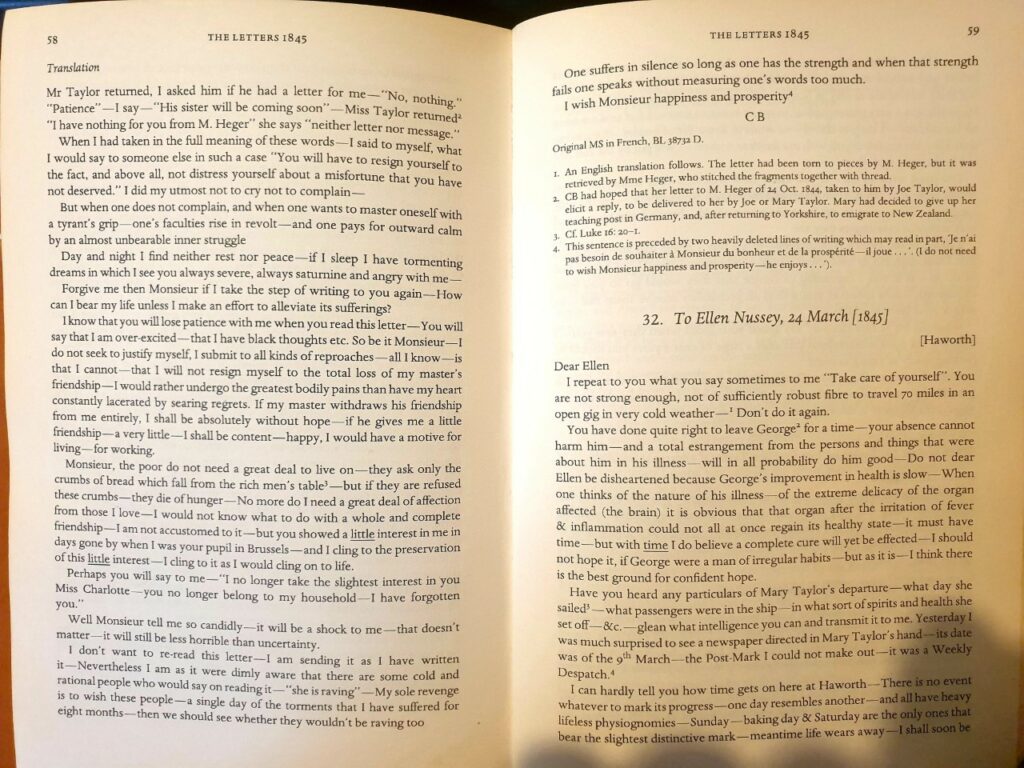

January is the longest month, but it can sometimes feel as if it lasts 31 weeks not 31 days. The nights are long and the days are cold and icy. It’s a time of year when people often feel ill or ‘under the weather’, and this was the certainly the case for Charlotte Brontë. In today’s post we’re going to look at two letters she sent on this day in 1852; two letters that lay bare the physical and psychological pressure under which she was living in the years that followed, in rapid succession, the deaths of her siblings Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë.

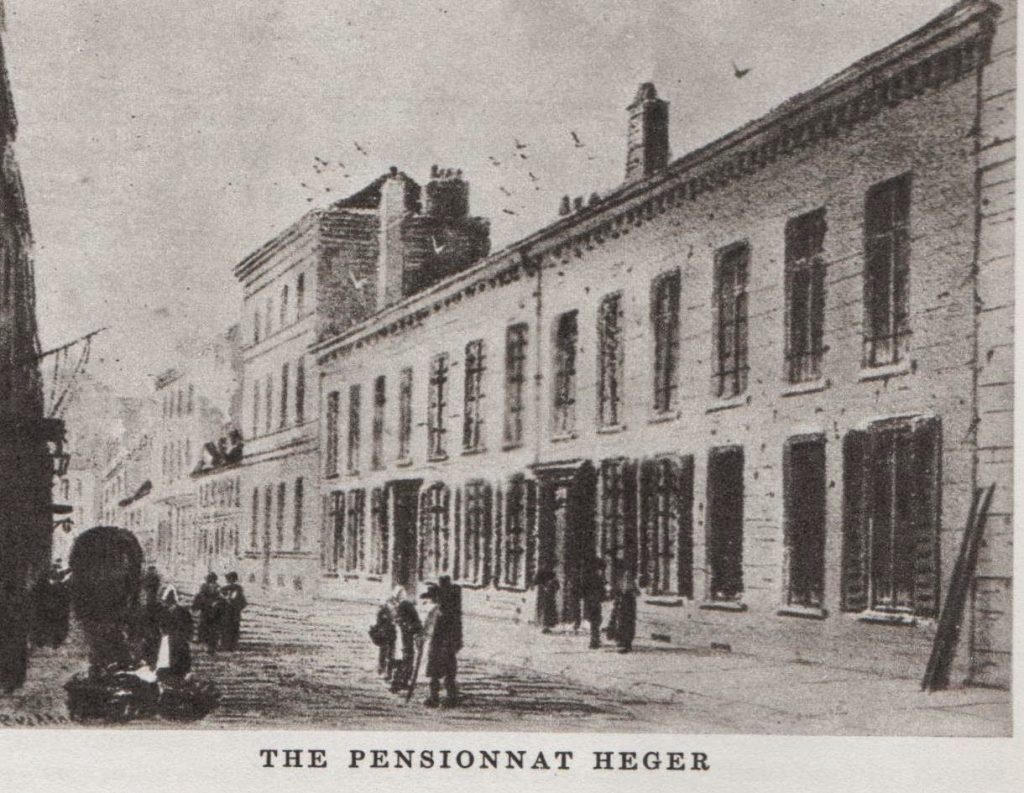

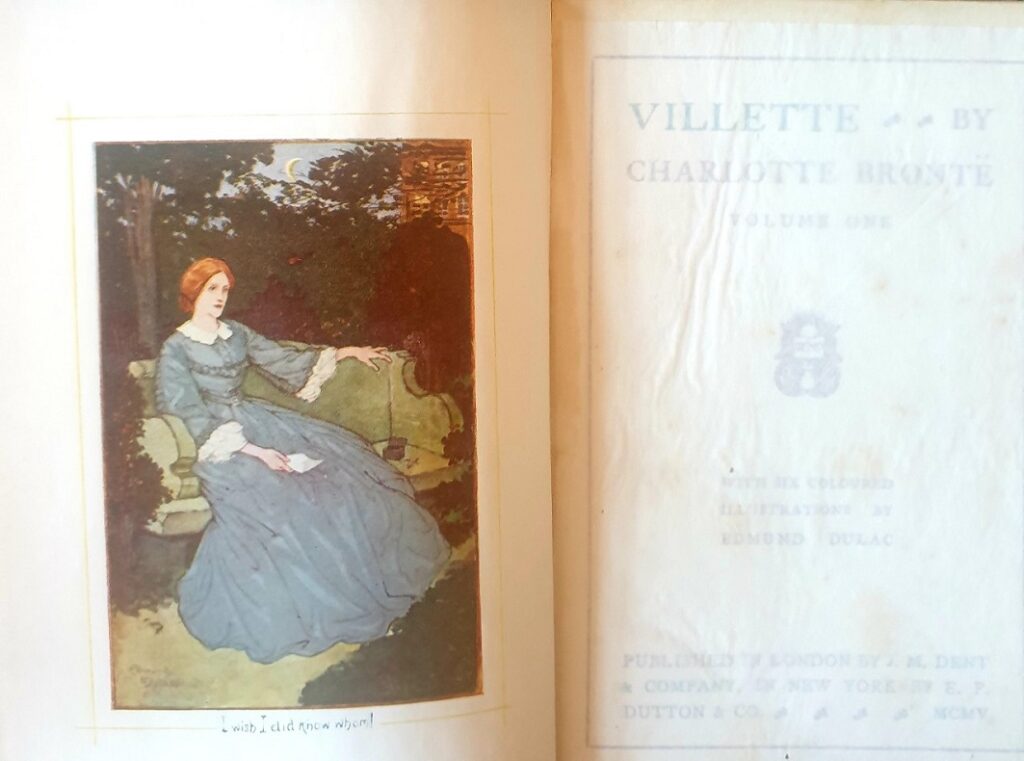

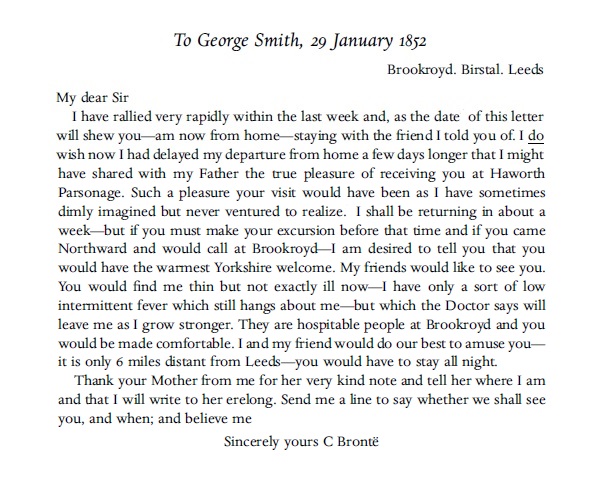

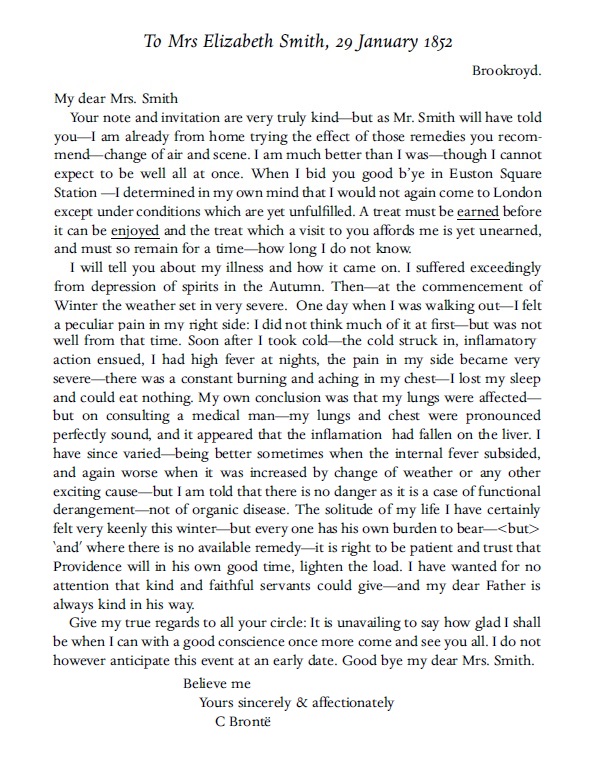

The letters, sent on the same day exactly 171 years ago, were sent to two members of the same family. Her publisher and friend (and some have speculated another unrequited love) George Smith, and his mother Elizabeth. Charlotte had visited the Smiths in London in June 1851, and it could be that they were expecting her to visit again soon – but she informs them that illness prevents her now and that she feels unable to return to London until certain conditions are fulfilled. It seems likely that Charlotte is referring to the completion of her novel Villette. Yesterday, the 28th of January, marked the anniversary of the novels publication in 1853. Let us turn now to the letters:

Charlotte is staying at Brookroyd in Birstall, the home of her great friend Ellen Nussey, but mental as well as physical torments continue to plague her. With the frankness typical of her letters, Charlotte reveals that she has suffered terribly from depression of spirits in the autumn, followed by “the solitude of life I have felt very keenly this winter.” It makes us think of another letter of Charlotte in which she talks of walking the moors alone, and seeing Anne and Emily everywhere. She loved to read their poetry but now she dare not, because to do so makes her long for her own death.

This must have been a terrifying time for Charlotte, because the physical symptoms she now suffered from were all too familiar to her. The wasting and inability to eat, a shooting pain in her side. Charlotte writes that “my own conclusion was that my lungs were affected.” Charlotte had seen these same symptoms before in all her siblings shortly before they died – she thought that she too had now contracted consumption. Thankfully Charlotte did not have tuberculosis, her lungs and chest were fine, but it is easy to imagine her terror as she waited for a diagnosis.

In her letter to George Smith, Charlotte writes, “You would find me thin but not exactly ill now”. Despite some of the representations of Charlotte on screen throughout the years, Charlotte was not only small she was very thin too – she is often described as ‘frail’ in appearance by those who knew her. Charlotte called herself, ‘the weakest, puniest, least promising of his [Patrick Brontë’s] six children’, and yet she outlived all her siblings.

Charlotte found herself challenged by mental and physical illness throughout much of her adult life, but she battled on and produced some of the greatest works of fiction the world has ever seen. The dark nights of winter were especially hard for her, but they passed. I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.