Today marks the 206th birthday of a woman who was a very close friend of Charlotte Brontë, and who was a remarkable person in her own right. Mary Taylor had been a school friend of Charlotte Brontë and Ellen Nussey, friendships that lasted a lifetime. In today’s post we’re going to look at a remarkable letter sent by Mary from the other side of the world!

We’ve looked at Mary in this blog many times before. The daughter of a wealthy cloth manufacturer who lived in the Red House, Gomersal, it was she who persuaded Charlotte and Emily Brontë to follow her to Brussels. Mary later emigrated to New Zealand, returning to England to become an author in her own right, as well as a travel journalist and a pioneering mountaineer. In fact, Mary led the first ever all-woman ascent of Mont Blanc as we can see in this picture – Mary, by this time aged 57, is on the left.

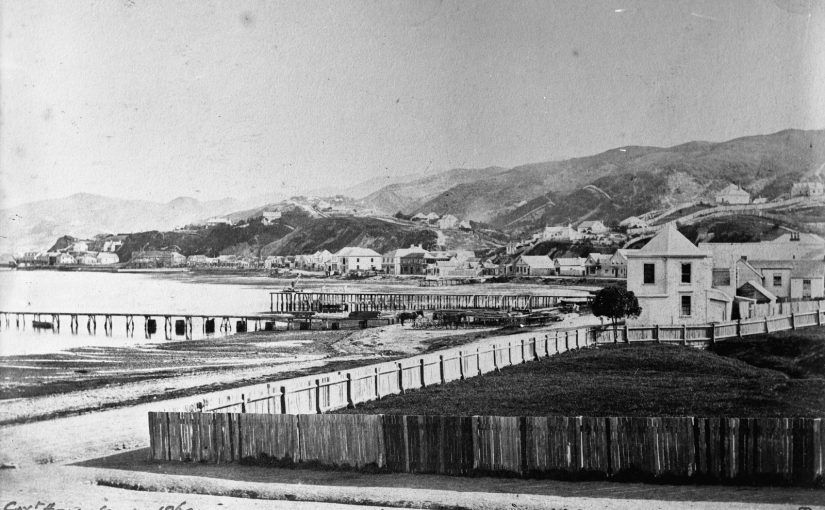

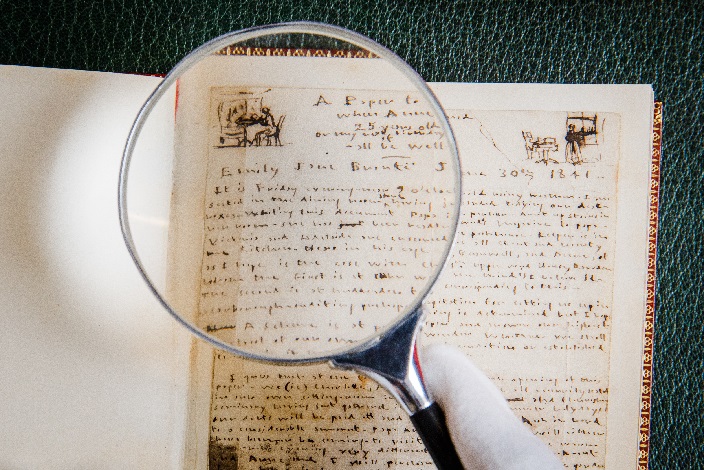

When Mary emigrated to New Zealand to set up her own business, Charlotte wrote that: “To me it is something as if a great planet fell out of the sky. Yet unless she marries in New Zealand she will not stay there long.” Alas, by the time Mary did return to Yorkshire Charlotte and all her siblings were no more, but a slow, ship led, correspondence took place between England and New Zealand (you can see 19th century Wellington, where Mary lived, at the top of this post). It is thanks to this correspondence that we have a remarkable letter sent to Charlotte by Mary on 24th July 1848. We have previously looked at the section of the letter in which Mary gives her, typically forthright, views on Jane Eyre but I now reproduce the letter in full as it also gives a remarkable insight into Mary’s life in New Zealand.

We see, for example, that Mary Taylor was indeed proposed to in New Zealand, but it was never likely to succeed. As Mary writes in her letter, she intended to use the proposal from a rich cattle drover to visit his daughter and go sightseeing with her. In her old age, Mary lived with a succession of maids from Switzerland and there seems little doubt that she preferred the company of women to men.

We also read of the fate of the cow that Charlotte bought for Mary as a leaving present. Unfortunately for the cow and Charlotte, it wasn’t a pleasant one.

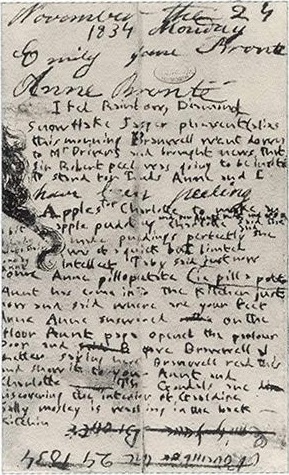

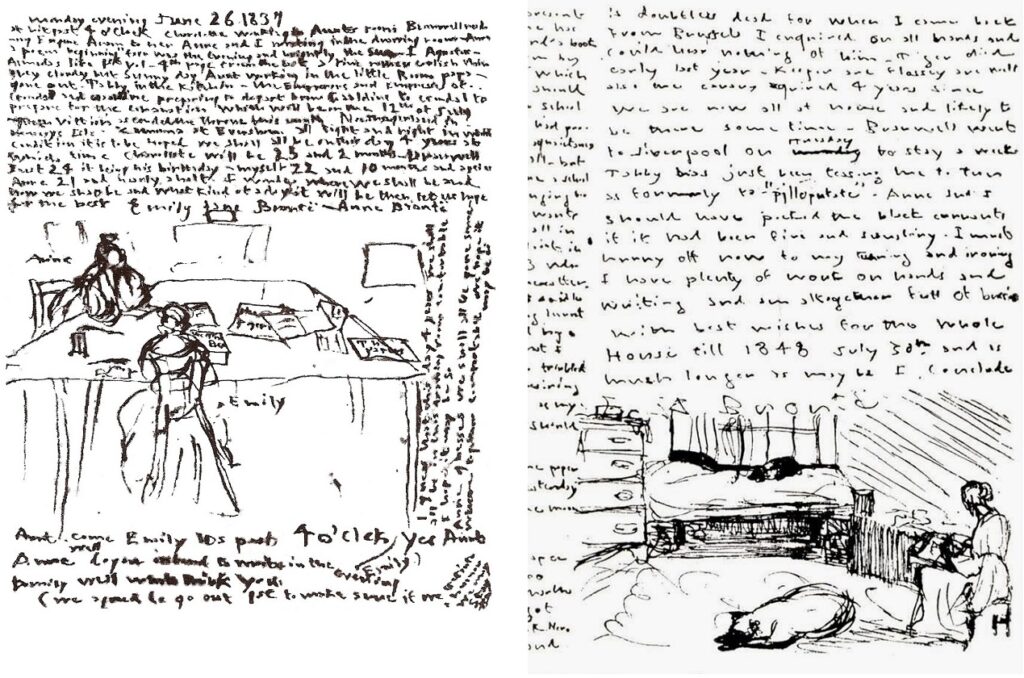

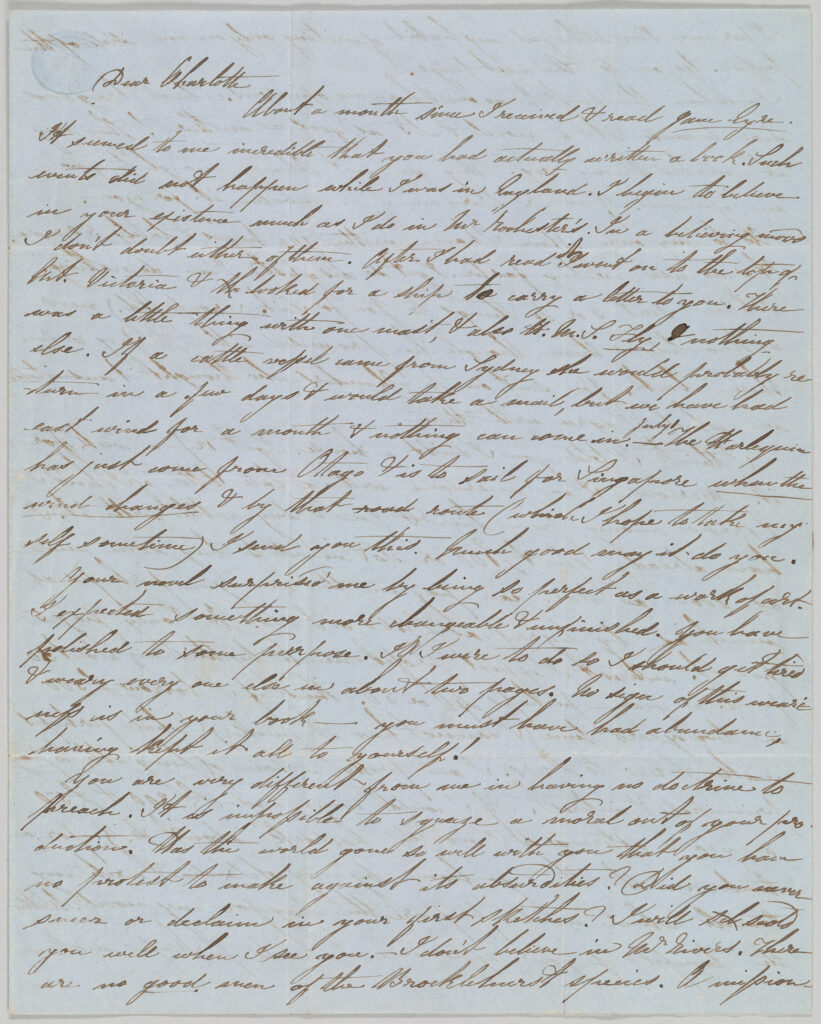

Even when separated by thousands of miles of water, the friendship between Cha rlotte Brontë and Mary Taylor endured, and she is pivotal in our understanding of the Brontës today. Happy birthday Mary Taylor, and to any of you who may have anniversaries approaching. I hope to see you all next week for another new Brontë blog post, and in the meantime I leave you with images of the actual letter itself (thanks to the Morgan Library & Museum of New York) and its transcription:

Dear Charlotte

About a month since I received & read Jane Eyre. It seemed to me incredible that you had actually written a book. Such events did not happen while I was in England. I begin to believe in your existence much as I do in Mr Rochester’s. In a believing mood I don’t doubt either of them. After I had read it I went on to the top of Mt. Victoria & looked for a ship to carry a letter to you. There was a little thing with one mast, & also H.M.S. Fly & nothing else. If a cattle vessel came from Sydney she would probably return in a few days & would take a mail, but we have had east wind for a month & nothing can come in.—July 1. The Harlequin has just come from Otago & is to sail for Singapore when the wind changes & by that road route (which I hope to take myself sometime) I send you this. Much good may it do you.

Your novel surprised me by being so perfect as a work of art. I expected something more changeable & unfinished. You have polished to some purpose. If I were to do so I should get tired & weary every one else in about two pages. No sign of this weariness is in your book—you must have had abundance, having kept it all to yourself!

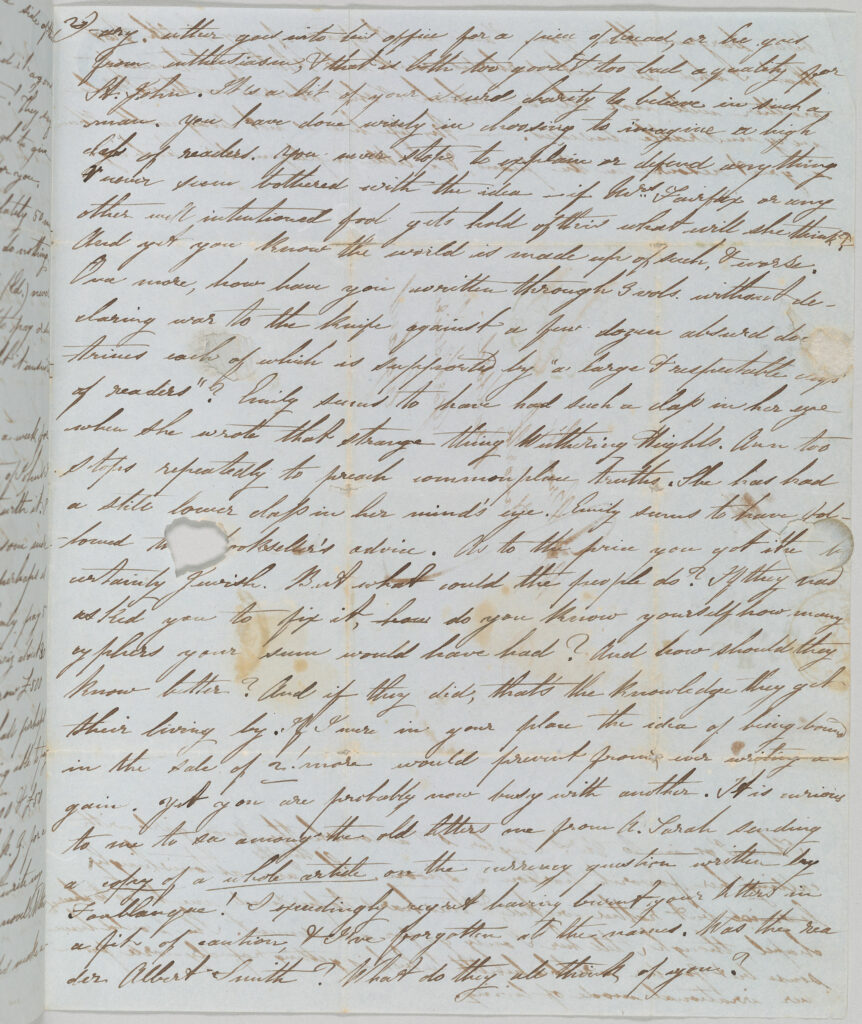

You are very different from me in having no doctrine to preach. It is impossible to squeeze a moral out of your production. Has the world gone so well with you that you have no protest to make against its absurdities? Did you never sneer or declaim in your first sketches? I will scold you well when I see you.—I don’t believe in Mr Rivers. There are no good men of the Brocklehurst species. A missionary either goes into his office for a piece of bread, or he goes from enthusiasm, & that is both too good & too bad a quality for St. John. It’s a bit of your absurd charity to believe in such a man. You have done wisely in choosing to imagine a high class of readers. You never stop to explain or defend anything & never seem bothered with the idea—if Mrs. Fairfax or any other well intentioned fool gets hold of this what will she think? And yet you know the world is made up of such, & worse. Once more, how have you written through 3 vols. without declaring war to the knife against a few dozen absurd doctrines each of which is supported by “a large & respectable class of readers”? Emily seems to have had such a class in her eye when she wrote that strange thing Wuthering Heights. Ann[e] too stops repeatedly to preach commonplace truths. She has had a still lower class in her mind’s eye. Emily seems to have followed t[he] [b]ookseller’s advice. As to the price you got it [was] certainly Jewish. But what could the people do? lf they had asked you to fix it, how do you know yourself how many cyphers your sum would have had? And how should they know better? And if they did, that’s the knowledge they get their living by. If I were in your place the idea of being bound in the sale of 2! more would prevent [me]from ever writing again. Yet you are probably now busy with another. It is curious to me to see among the old letters one from A[unt] Sarah sending a copy of a whole article on the currency question written by Fonblanque! I exceedingly regret having burnt your letters in a fit of caution, & I’ve forgotten all the names. Was the reader Albert Smith? What do they all think of you?

I perceive I’ve betrayed my habit of writing only on one side of the paper. Go onto the next page.

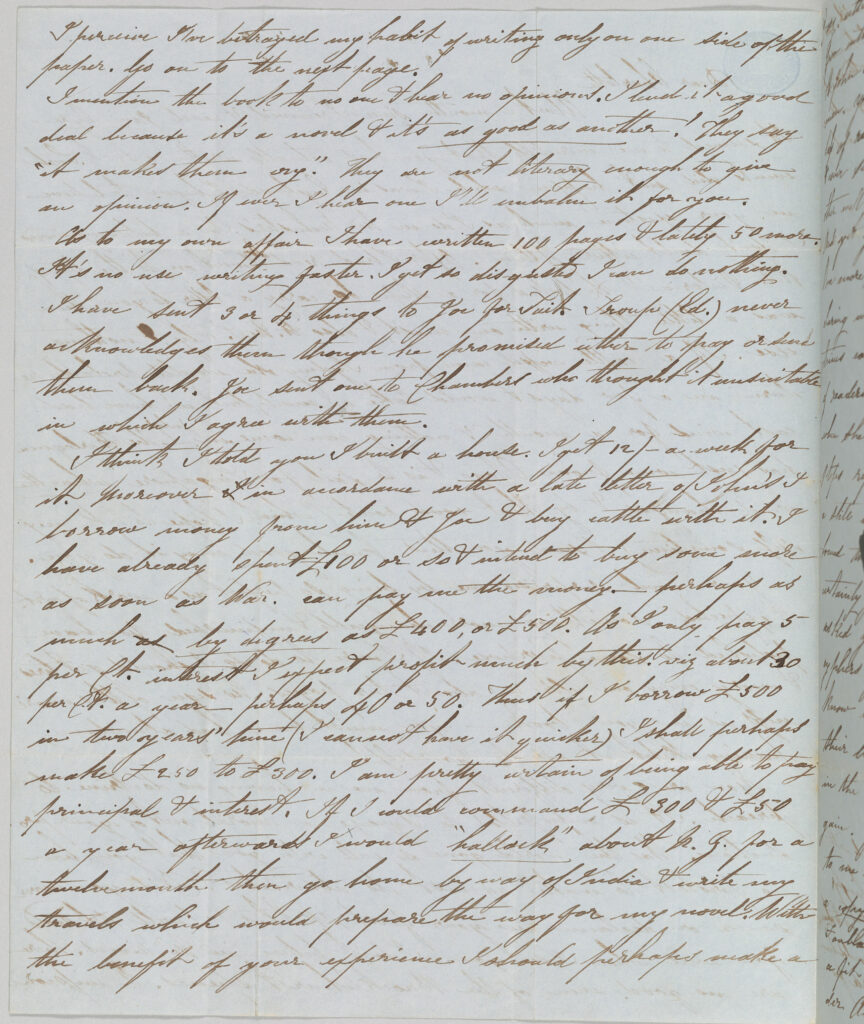

I mention the book to no one & hear no opinions. I lend it a good deal because it’s a novel & it’s as good as another! They say “it makes them cry.” They are not literary enough to give an opinion. If ever I hear one I’ll embalm it for you.

As to my own affair I have written 100 pages & lately 50 more. It’s no use writing faster. I get so disgusted I can do nothing. I have sent 3 or 4 things to Joe for Tait. Troup (Ed.) never acknowledges them though he promised either to pay or send them back. Joe sent one to Chambers who thought it unsuitable in which I agree with them.

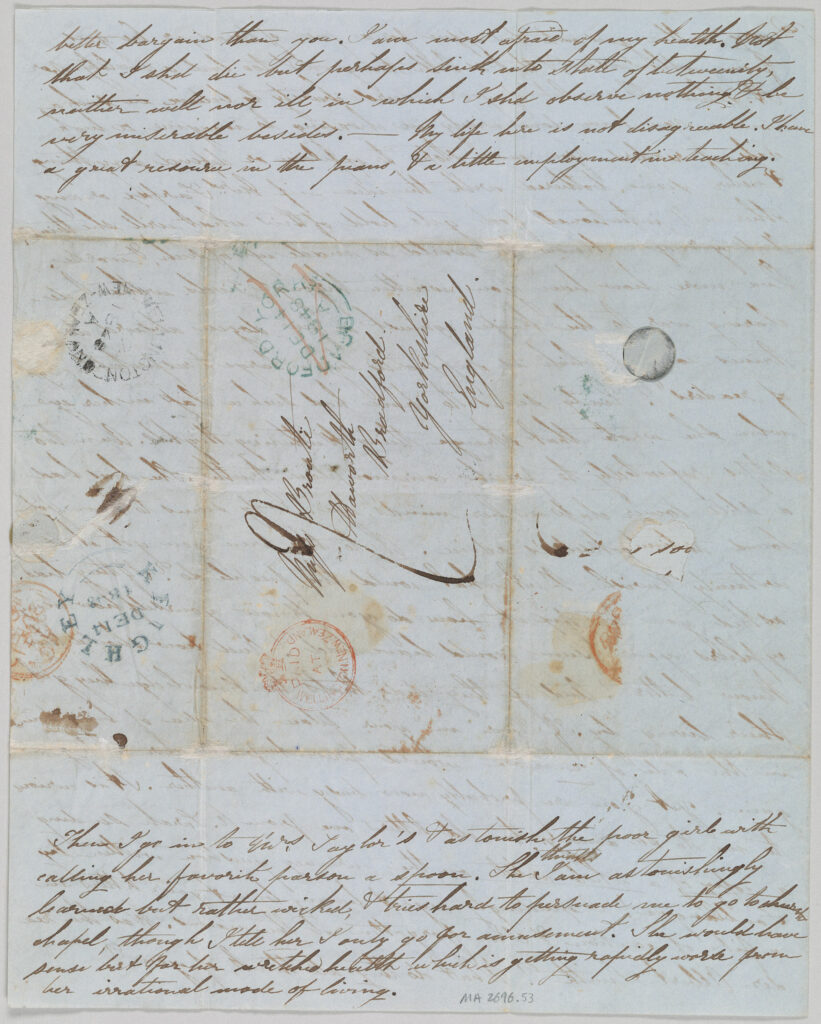

I think I told you I built a house. I get 12/– a week for it. Moreover I in accordance with a late letter of John’s I borrow money from him & Joe & buy cattle with it. I have already spent £100 or so & intend to buy some more as soon as War[ing] can pay me the money. —perhaps as much as by degrees as £400, or £500. As I only pay 5 per Ct. interest I expect [to] profit much by this. viz about 30 per Ct. a year—perhaps 40 or 50. Thus if I borrow £500 in two years’ time (I cannot have it quicker) I shall perhaps make £250 to £300. I am pretty certain of being able to pay principal & interest. If I could command £300 & £50 a year afterwards I would “hallock” about N.Z. for a twelvemonth then go home by way of India & write my travels which would prepare the way for my novel. With the benefit of your experience I should perhaps make a better bargain than you. I am most afraid of my health. Not that I should die but perhaps sink into state of betweenity, neither well nor ill, in which I should observe nothing & be very miserable besides. —My life here is not disagreeable. I have a great resource in the piano, & a little employment in teaching.

Then I go to Mrs. Taylor’s & astonish the poor girl with calling her favourite parson a spoon. She thinks I am astonishingly learned but rather wicked, & tries hard to persuade me to go to church chapel, though I tell her I only go for amusement. She would have sense but for her wretched health which is getting rapidly worse from her irrational mode of living.

[letter continues on a separate sheet in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library] I can hardly explain to you the queer feeling of living as I do in 2 places at once. One world containing books England & all the people with whom I can exchange an idea; the other all that I actually see & hear & speak to. The separation is as complete as between the things in a picture & the things in the room. The puzzle is that both move & act, & [I] must say my say as one of each. The result is that one world at least must think me crazy. I am just now in a sad mess. A drover who has got rich with cattle dealing wanted me to go & teach his daughter. As the man is a widower I astonished this world when I accepted his proposal, & still more because I asked too high a price (£70) a year. Now that I have begun the same people can’t conceive why I don’t go on & marry the man at once which they imagine must have been my original intention. For my part I shall possibly astonish them a little more for I feel a great inclination to make use of his interested civilities to visit his daughter & see the district of Porirua.

If I had a little more money & could afford a horse (she rides) I certainly would. But I can see nothing till I get a horse, which I shall have if I’m lucky in 2 or 3 years.

I have just made acquaintance with Dr & Mrs. Logan. He is a retired navy doctor & has more general knowledge than any one I have talked to here. For instance he had heard of Phillippe Egalite—of a camera obscura; of the resemblance the English language has to the German &c &c. Mrs. Taylor Miss Knox & Mrs. Logan sat in mute admiration while we mentioned these things, being employed in the meantime in making a patchwork quilt. Did you never notice that the women of the middle classes are generally too ignorant to talk to? & that you are thrown entirely on the men for conversation? There is no such feminine inferiority in the lower. The women go hand in hand with the men in the degree of cultivation they are able to reach. I can talk very well to a joiner’s wife, but seldom to a merchant’s.

I must now tell you the fate of your cow. The creature gave so little milk that she is doomed to be fatted & killed. In about 2 months she will fetch perhaps £15 with which I shall buy 3 heifers. Thus you have the chance of getting a calf sometime. My own thrive well & possibly I [shall] have a calf myself. Before this reaches England I shall have 3 or 4.

It’s a pity you don’t live in this world that I might entertain you about the price of meat. Do you know I bought 6 heifers the other day for £23? & now it is turned so cold I expect to hear one half of them are dead. One man bought 20 sheep for £8 & they are all dead but 1. Another bought £150 & has 40 left; and people have begun to drive cattle through a valley into the Wairau plains & thence across the straits of Wellington. &c &c. This is the only legitimate subject of conversation we have the rest is gos[sip] concerning our superiors in station who don’t know us on the road, but it is astonishing how well we know all their private affairs, making allowance always for the distortion in our own organs of vision.

I have now told you everything I can think of except that the cat’s on the table & that I’m going to borrow a new book to read. No less than an account of all the systems of philosophy of modern Europe. I have lately met with a wonder a man who thinks Jane Eyre would have done better [to] marry Mr Rivers! He gives no reasons—such people never do.

Mary Taylor