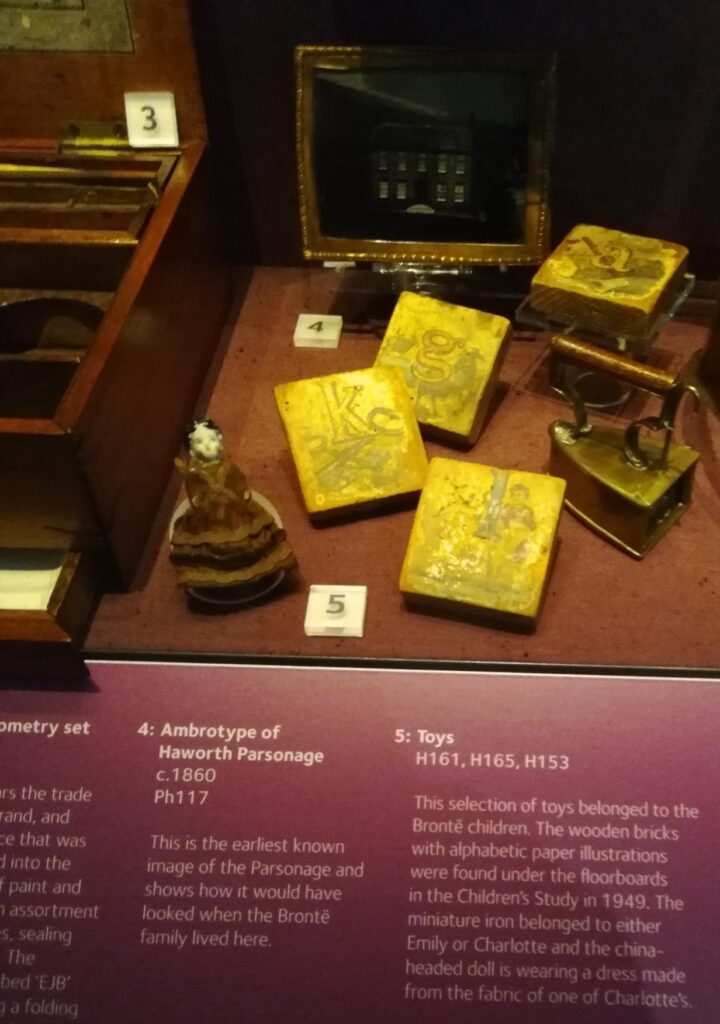

If you’re lucky enough to have been to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth you’ll know that it’s full of treasures large and small. Sometimes these have come from surprising sources – such as the toys the young Brontës played with which were found under the floorboards during renovation work. In today’s post we’re going to look at a seemingly unassuming tin box which held a very important secret for over half a century.

The outside of the box is unassuming indeed, it’s a simple rectangular tin of the kind that could be found anywhere at any time – but it’s provenance is the first thing which makes it special, for it was gifted from Branwell Brontë to his sister Emily Brontë.

Emily used it as a sewing box – inside it were found threads of various colours, bobbins, buttons and lace edges used on collars. A fascinating glimpse into the world of Emily Brontë, who like all her sisters was taught to sew from an early age by Aunt Branwell, but nothing surprising. The surprise came much later, and over 300 miles from Haworth – and it completely changed our understanding of the Brontës.

After the death of Charlotte Brontë in 1855 and of Patrick Brontë in 1861 the Brontë line had come to a tragic end. Many Brontë possessions were left to friends of the family such as long standing servant Martha Brown, but the majority came into the possession of Charlotte’s widower Arthur Bell Nicholls. He took them with him back to his childhood home of Banagher, Ireland (that’s it at the head of this post) and to his second wife Mary Bell. Their home became a shrine to Arthur’s enduring love of Charlotte Brontë – as Arthur’s great-niece Marjorie Gallop later recalled:

‘With generous loyalty, Mary Nicholls made every room in the house a Brontë shrine. The drawing room was hung with the sisters’ drawings, Mr. Brontë’s gun leaned up against the dining room wall, and Charlotte’s portrait overlooked the sofa on which Mary used to rest. One day it broke away from the wall, missed a table which stood below it, and fell on to Mary. Neither the portrait nor Mary was harmed. When Arthur died, Mary had his coffin placed beneath the portrait until it was carried from the house.’

In 1955, a century after Charlotte’s death, an even closer relative of Arthur, his niece (by then in her nineties) painted a similar picture:

‘Later on, Arthur Nicholls married my aunt, Mary, who made him a devoted wife, and treasured everything that had belonged to Charlotte. My grandmother and my aunt loved to tell me about her, and I loved to listen. Charlotte’s wedding dress, so tiny, and her tiny white gloves, buttoned at the wrist, my aunt gave to Allen Nicholls’ [Arthur’s brother] youngest daughter, who had been given the names of Charlotte Brontë at her christening. Later on she often stayed at the Hill House, and came to love Uncle Arthur, as did all the young people; and, after his death, feeling that these things were peculiarly sacred, she had them burned.

Half way up the stairs at the Hill House stood Mr. Brontë’s handsome old grandfather clock, and near it hung a plaque of Branwell; over the sideboard in the dining-room was the well-known photograph of Haworth Rectory and the graveyard, and in the corner near the door was Mr. Brontë’s old gun. In the drawing room was Charlotte’s portrait, and also one of Thackeray, as well as many framed drawings of the three Brontë sisters. In a glass-fronted case were all the books of the three sisters. The portraits of his sisters by Branwell, that now hang in the National Gallery, Arthur Nicholls disliked – he thought they were “such ugly representations of the girls.”’

One other thing that we know Arthur kept in Banagher was the tin sewing box of Emily Brontë. He must have loved to take out these items and hold them again, as if calling up visions of the Yorkshire family he had loved. Time didn’t diminish these memories or the pleasure obtained from them, for in 1895, 40 years after the passing of Charlotte, Arthur once again held Emily’s sewing box in his hand. Perhaps he was turning it over and over in his hand, or perhaps something made him look at it more closely than before. There was a click unheard for many decades, and a secret compartment flipped open – what was inside had not been seen for nearly half a century.

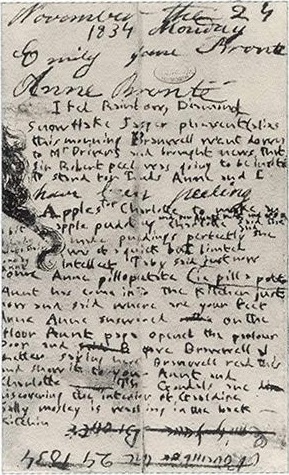

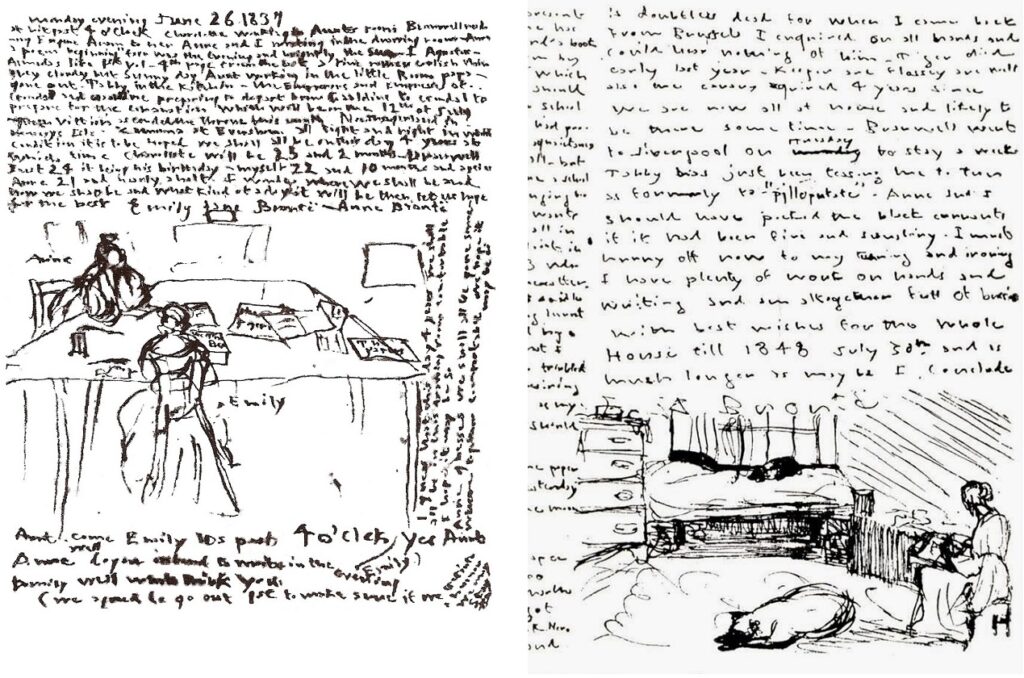

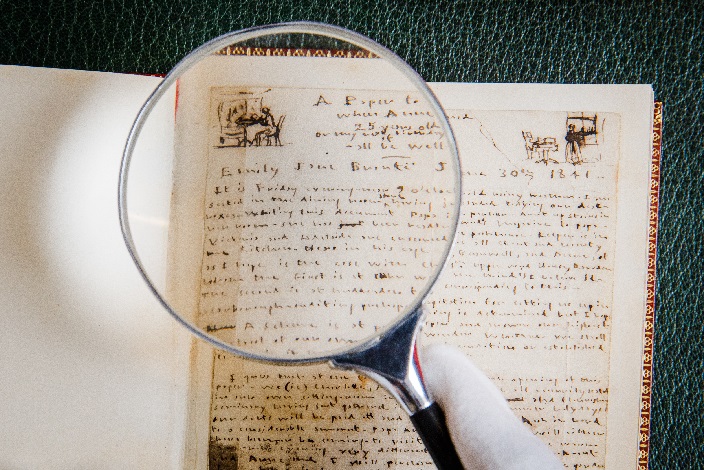

When I think of this event, words spoken 27 years later. Howard Carter looked into a tomb that for many centuries had been undiscovered – behind him Lord Carnarvon asked, “Can you see anything?” Carter’s reply (oft misquoted) was, “Yes, it is wonderful.” What Arthur saw was wonderful indeed – small, ageing scraps of paper with dense, untidy writing on them and scribbled illustrations; hidden away since 1845 they were the diary papers of Emily and Anne Brontë.

These diary papers were written jointly by Emily and Anne in 1834 and 1837 and then separately by the sisters in 1841 and 1845.

These papers are small and short, but they vividly demonstrate everyday life in the parsonage and the inner thoughts of the two sisters who wrote them. Through these diary papers we hear of Charlotte making apple pudding, of Emily and Anne longing to play rather than doing home or housework, of their early Gondal compositions, of the careers of Charlotte, Branwell and Anne, of the Brontë pets and of a journey to York, of Anne’s despair at what she has seen at Thorp Green Hall, of Charlotte’s visit to Haworth – a visit that would lead to Jane Eyre.

So many interesting facts and stories are contained within these tiny sheets of paper, but the insight into the character of the two writers is just as fascinating – and it gives us a different picture of Emily Brontë in particular. Emily’s writing is often dark and mysterious – her poems talk frequently of death and of a desire to leave this world, and yet her diary papers, in contrast to Anne’s later entries, are always cheery and optimistic. In the diary papers we see the real Emily Brontë, not the one she presented in her magnificent writing: we see the Emily that made an acquaintance say “Martha Brown loved her, she said she was so kind”, and the Emily that Ellen Nussey wrote of – the Emily that loved to laugh and play practical jokes; the Emily that family friend John Greenwood wrote of dancing down the garden and calling out in her sweet voice.

These diary papers are literary treasures, and yet they could easily have remained hidden and unseen for all time. Only a chance discovery brought them to light, so what other Brontë discoveries are still waiting to be found? At the close of their 1845 diary papers both Emily and Anne wrote of plans to compose a new entry on 30th July 1848 – no trace of those diary papers has yet been found, was it written and may it one day yield us a glimpse of the Brontës after they have become published authors?

I hope to find you here next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post, have a happy and healthy week ahead.