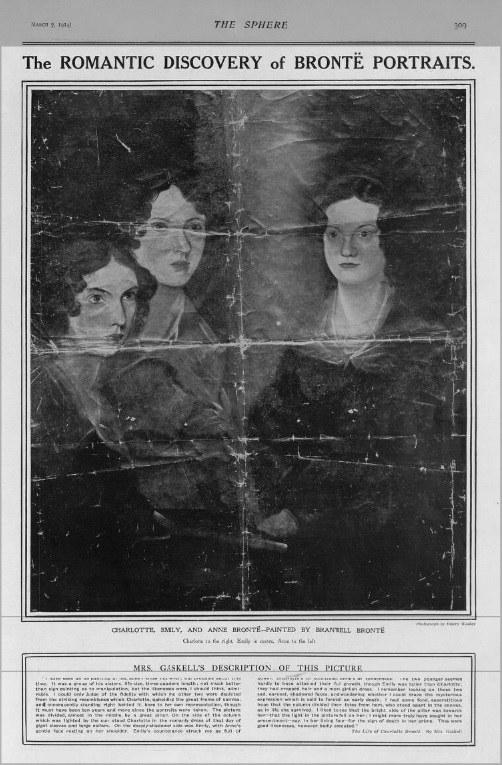

There is one iconic image of the Brontë sisters. In fact, there is only one complete and authentic portrait of the three writing sisters together. It divides opinion still, and it could be said that it’s far from ideal as it shows Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë in their youth but it still caused a stir when it was exhibited for the first time on this day in 1914 at the National Portrait Gallery (pictured above). In today’s post we’re going to look at the unveiling of the Brontë pillar portrait.

The painting of the sisters was completed by their brother Branwell Brontë in 1834, although there is no certainty over the date. That would make Charlotte 17 or 18 at the time of the portrait, Emily 15 or 16 and Anne 14. The painter himself would have been 16 or 17, and so whilst Branwell went on to be a fine portrait painter this is hardly one of his more accomplished works.

It is, however, in my opinion by far his most important work as it is the only completed portrait of the sisters together (there is an unfinished sketch which has become known as the ‘gun portrait’ as it shows a seated Branwell holding a shotgun.) I also love the way that Anne and Emily are shown side by side, as these inseparable sisters habitually were at this time.

In between Anne and Emily and Charlotte is the feature which gives this portrait its common nomenclature – a pillar. It is commonly thought that Branwell painted himself in this position, but that he disliked his attempt at self-portraiture so much that he painted a large pillar over himself, but is this true? Over time the pillar is fading and the figure beneath it is becoming more prominent – it’s certainly a male figure but it seems to be wearing a neckerchief of the kind always worn by his father Patrick Brontë. Could it be then that Patrick was originally pictured in a portrait with his daughters, and that Branwell painted over him at a later date (possibly when he was in one of his rages against his father)? Time, and its affect on the obscuring pillar, may one day yield the answer, but for now the pillar keeps its secret.

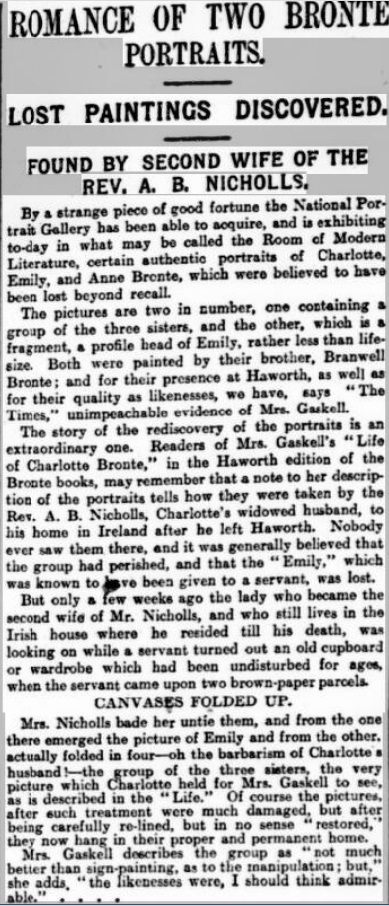

This is a picture used to keeping its secret, for until 1914 it was well known but presumed lost. I bring you below two contemporary reports which detail its amazing discovery:

The text reads: “The ROMANTIC DISCOVERY of BRONTE PORTRAITS. CHARLOTTE, EMILY, AND ANNE BRONTE– PAINTED BY BRANWELL BRONTE Charlotte to the right, Emily in centre, Anne to the left Photograph by Emery Walker MRS. GASKELL’S DESCRIPTION OF THIS PICTURE I have seen an oil painting of his, done I know not when, but probably about this time. It was a group of his sisters, life-size, three-quarters length not much better than sign-painting as to manipulation, but the likenesses were, I should think, admirable. I could only Judge of the fidelity with which the other two were depicted from the striking resemblance which Charlotte, upholding the great frame of canvas, and consequently standing right behind It, bore to her own representation, though It must have been ten years and more since the portraits were taken. The picture was divided, almost In the middle, by a great pillar. On the side of the column which was lighted by the sun stood Charlotte in the womanly dress of that day of gigot sleeves and large collars. On the deeply-shadowed side was Emily, with Anne’s gentle face resting on her shoulder. Emily’s countenance struck me as full of power, Charlotte’s of solicitude, Anne’s of tenderness. The two younger seemed hardly to have attained their full growth, though Emily was taller than Charlotte; they had cropped hair and a more girlish dress. I remember looking on those two sad, earnest, shadowed faces, and wondering whether I could trace the mysterious expression which Is said to foretell an early death. I had some fond, superstitious hope that the column divided their fates from hers, who stood apart In the canvas, as in life she survived. I liked to see that the bright side of the pillar was towards her that the light in the picture fell on her; I might more truly have sought in her presentment nay, in her living face for the sign of death in her prime. They were good likenesses, however badly executed.” The Life of Charlotte Bronte. By Mrs. Gaskell”

We can also see from the image of the portrait in 1914 and of it now, earlier in the post, that the National Portrait Gallery have carried out some restoration on the piece. We now turn to a report from the day of the portrait’s unveiling:

The Yorkshire Evening Post comments that the picture had been folded by Charlotte’s widower Arthur and had remained unseen since it came into his possession, adding the comment: “Oh the barbarism of Charlotte’s husband!”

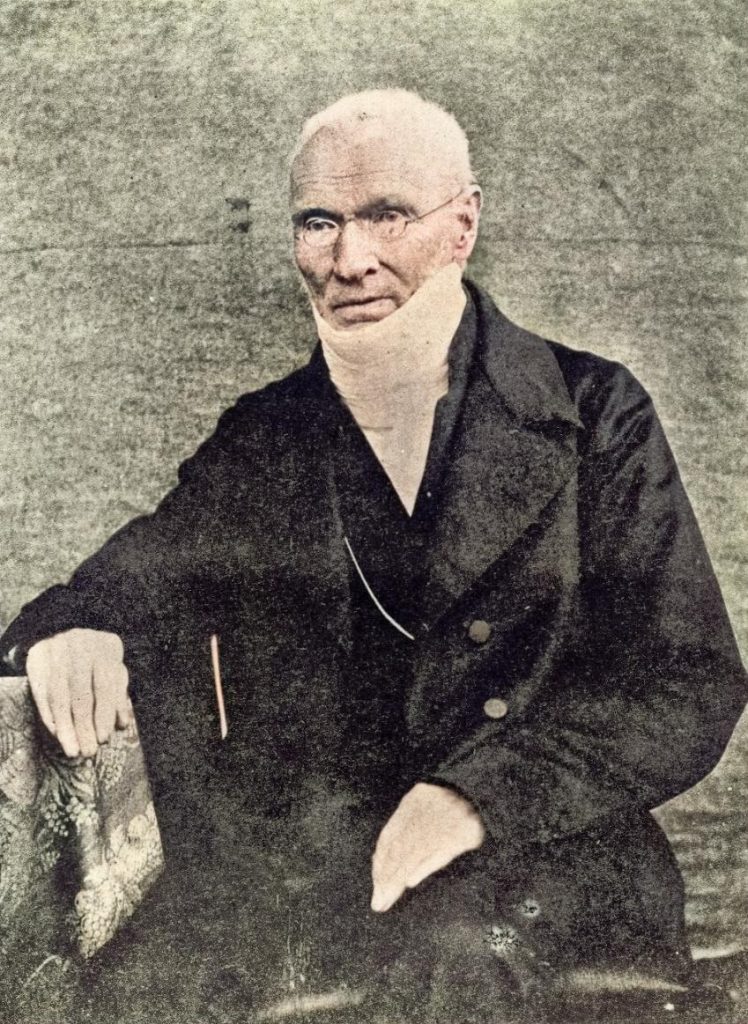

It is often thought that Arthur folded the picture because he disliked Branwell (the brother was at loggerheads with sister Charlotte throughout the time that Arthur knew them), but in fact that’s far from the truth. Arthur must have valued Branwell because he kept a portrait of him by Joseph Leyland on his wall, and we also hear, from a niece of Arthur, why he hid the pillar portrait away:

‘The portraits of his sisters by Branwell, that now hang in the National Gallery, Arthur Nicholls disliked – he thought they were “such ugly representations of the girls.”’

To be fair, Arthur had never seen the sisters in their youth, so it could be, whether he thought it ugly or not, that it was a good representation. I personally think it’s a beautiful portrait because it is clearly painted with love, and it’s certainly a historically beautiful portrait.

The Brontë sisters themselves were all skilled artists in their own rights, of course, but it is with their pens that they painted portraits that will lost as long as our world keeps turning. I hope you can join me next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.