Two rather interesting anniversaries in the Brontë story have their anniversaries on this day, and they both tell us a lot about the development of the young Brontës as writers. On this day 1829, Charlotte Brontë wrote ‘The History Of The Year’, and on this day in 1837 Charlotte received a letter from poet laureate Robert Southey telling her that literature could not and should not be a woman’s work. We’ve looked at both of these things in previous years, but as this is their anniversary day we’re going to look back at both these incidents in today’s new post.

Let’s begin chronologically and head back nearly two hundred years to 1829. Aged 12 Charlotte is now head of the siblings, their elder sisters Maria and Elizabeth Brontë having died tragically four years earlier. Charlotte’s ‘history’ gives us great insight into the Brontë family at this time, and we see a tight knit community, one who loves to play together, and crucially one who loves to create together. Here is the document in full:

‘Once Papa lent my sister Maria a book. It was an old geography and she wrote on its blank leaf, “Papa lent me this book.” The book is an hundred and twenty years old. It is at this moment lying before me while I write this. I am in the kitchen of the parsonage house, Haworth. Tabby the servant is washing up after breakfast and Anne, my youngest sister (Maria was my eldest), is kneeling on a chair looking at some cakes which Tabby has been baking for us. Emily is in the parlour brushing it. Papa and Branwell are gone to Keighley. Aunt is up stairs in her room and I am sitting by the table writing this in the kitchin. Keighley is a small town four miles from here. Papa and Branwell are gone for the newspaper, the Leeds Intelligencer, a most excellent Tory news paper edited by Mr Edward Wood for the proprietor Mr Hernaman. We take and 2 and see three newspapers a week. We take the Leeds Intelligencer, party Tory, and the Leeds Mercury, Whig, edited by Mr Baines and his brother, son in law and his 2 sons, Edward and Talbot. We see the John Bull; it is a High Tory, very violent. Mr Driver lends us it, likewise Blackwood’s Magazine, the most amiable periodical there is. The editor is Mr Christopher North, an old man, 74 years of age. The 1st of April is his birthday. His company are Thomas Tickler, Morgan O’Doherty, Macrabin, Mordecai Mullion, Warrell, and James Hogg, a man of most extraordinary genius, a Scottish shepherd.

Our plays were established: Young Men, June 1826; Our Fellows, July 1827; Islanders, December 1827. These are our three great plays that are not kept secret. Emily’s and my bed plays were established the 1st December 1827, the others March 1828. Their nature I need not write on paper, for I think I shall always remember them. The Young Men took its rise from some wooden soldiers Branwell had, Our Fellows from Aesop’s Fables, and the Islanders from several events which happened. I will sketch out the origins of our plays more explicitly if I can. March 12, 1829.

Young Men’s

Papa brought Branwell some soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed and I snatched up one and exclaimed: “This is the Duke of Wellington! It shall be mine!” when I had said this, Emily likewise took one up and said it should be hers; when Anne came down, she said one should be hers. Mine was the prettiest of the whole, and the tallest, and the most perfect in every part. Emily’s was a grave-looking fellow, and we called him “Gravey”. Anne’s was a queer little thing, much like herself. He was called Waiting Boy. Branwell chose Bonaparte. March 12, 1829.

The Origin Of The O’Dears

The origin of the O’Dears was as follows. We pretended we had each a large island inhabited by people 6 miles high. The people we took out of Aesop’s Fables. Hay Man was my chief man, Boaster Branwell’s, Hunter Anne’s, and Clown Emily’s. Our chief men were 10 miles high except Emily’s who was only 4. March 12, 1829.

The Origin Of The Islanders

The origin of the Islanders was as follows. It was one wet night in December. We were all sitting round the fire and had been silent some time, and at last I said, ‘Suppose we each had an island of our own.’ Branwell chose the Isle of Man, Emily Isle of Arran and Bute Isle, Anne, Jersey, and I chose the Isle of Wight. We then chose who should live in our islands. The chief of Branwell’s were John Bull, Astley Cooper, Leigh Hunt, etc, etc. Emily’s Walter Scott, Mr Lockhart, Johnny Lockhart etc, etc. Anne’s Michael Sadler, Lord Bentinck, Henry Halford, etc, etc. And I chose Duke of Wellington & son, North & Co., 30 officers, Mr Abernethy, etc, etc. March 12, 1829.’

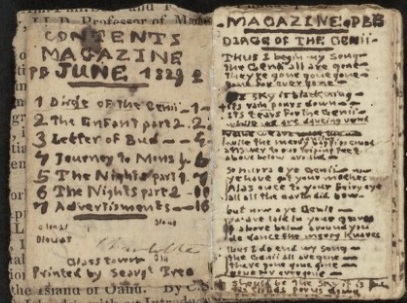

By 1829 we can see that the Brontë sisters, and brother, were fierce creators, conjuring lands and characters out of their imaginations – and by this time they were already putting them into print, as some of the tiny books written by the Brontës (by Charlotte and Branwell at this date) date from this year – like the 1829 manuscript above, only readable under a powerful magnifying glass.

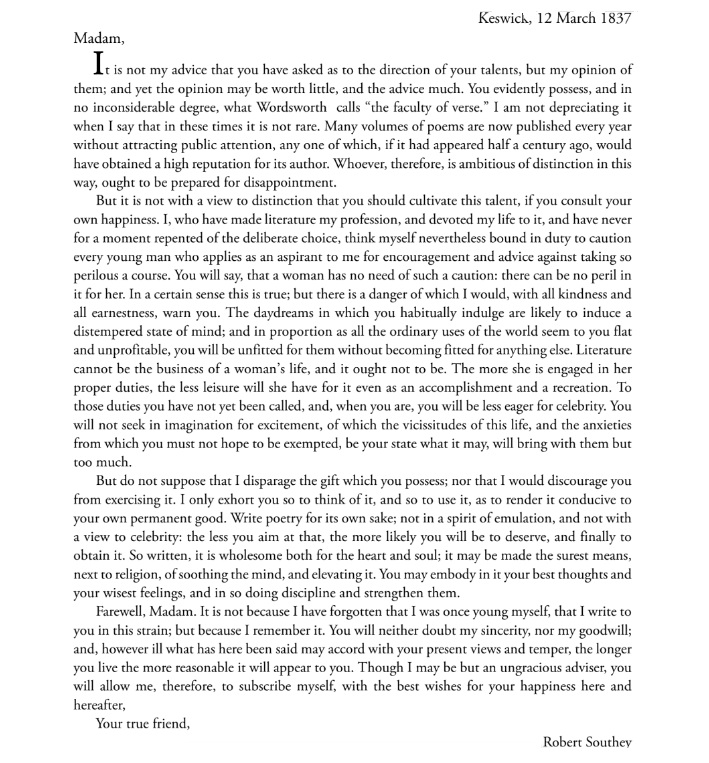

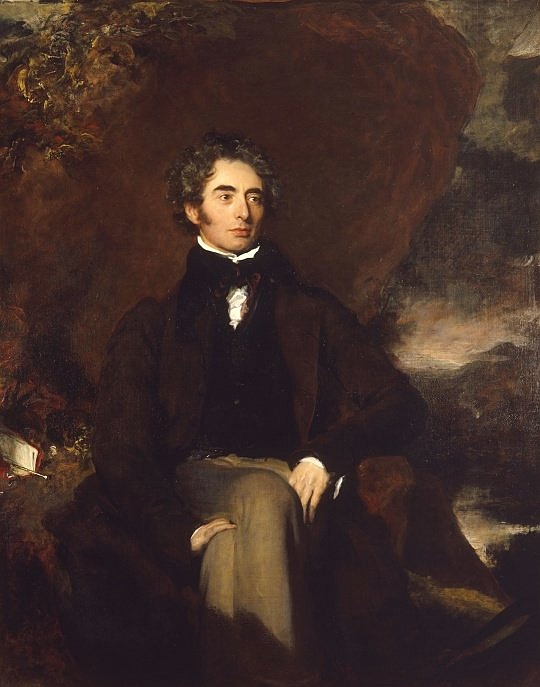

Fast forward eight years and, thankfully, the Brontë love of writing has not diminished. By 1837 they were all in love with poetry and forthright Charlotte had sent some of her verse for appraisal by the most exalted poet in the land (alongside his friend William Wordsworth): poet laureate Robert Southey. Alas, we don’t have her original letter to Southey, but we do have his reply, and it’s a less than perceptive one as you can read below:

Charlotte treasured the letter and kept the original envelope, upon which she wrote: ‘Southey’s advice. To be kept forever.’ She also wrote back to Southey, but rather than giving it to him with both barrels, she wrote:

‘Once more allow me to thank you, with sincere gratitude. I trust I shall never more be ambitious to see my name in print – if the wish should rise I’ll look at Southey’s autograph and suppress it. It is honour enough for me that I have written to him and received an answer. The letter is consecrated; no one shall ever see it but Papa and my brother and sisters. Again I thank you – this incident I suppose will be renewed no more. If I live to be an old woman I shall remember it thirty years hence as a bright dream.’

Thank goodness that Charlotte and her sisters didn’t, after all, allow this letter to stop them writing. – how surprised would Southey be to see Charlotte and her sisters remembered alongside him in Westminster Abbey’s ‘Poet’s Corner’ at the head of this post? In this we see the value of persistence and the value of following your dream. If you dream of writing a book go ahead and do, and don’t let anyone or anything tell you to stop. I won’t stop writing about the remarkable Brontës while I have breath in my body, so have a great day and I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post.