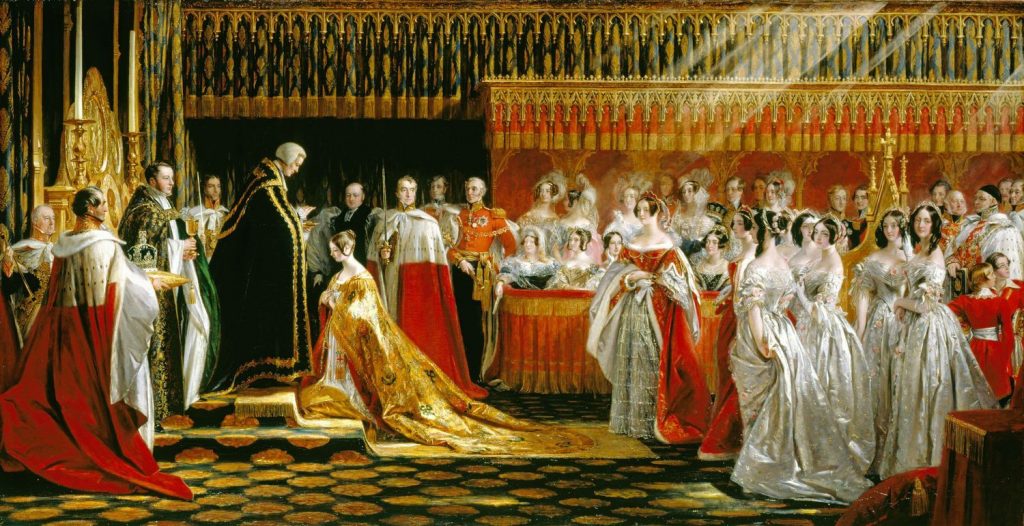

Whether you festooned your home in union flags or hid under the duvet, yesterday’s coronation of King Charles III was hard to avoid. In today’s new Brontë blog post we’re going to look at what the Brontës may have thought of the grand coronation in Westminster Abbey.

Firstly, however, I want to address the technical gremlins which beset my blog post last week. Those who subscribe to this site (thank you!) will have had no problem reading about the Thackeray’s accounts of Charlotte Brontë and her blue dress, but it simply didn’t show up on the website itself. Having investigated this thoroughly I can reveal that I have absolutely no idea why this happened – although it did happen once last year as well. If it happens again then I will migrate this site to a new system – it will have a slightly different look, but you’ll still be able to access the old posts from the last 8 years, and there will still be a new Brontë blog post every Sunday.

Assuming/hoping that people will be able to read this, I continue. Would the Brontë family have been fans of the coronation? As always, of course, until we invent the time machine we cannot say with complete certainty. By looking at their writing, letters and diaries, however, we get clues to what their beliefs were, allowing us to indulge in a little educated speculation.

The Brontës, perhaps alongside Charles Dickens, are often thought of as the quintessentially Victorian authors, just as Jane Austen is often seen as a representative of the earlier Regency period. In fact none of the Brontë sisters were born during the reign of Queen Victoria, they were all born during the Regency period when the future King George IV was ruling as Prince Regent in lieu of his ill father George III. Queen Victoria, niece of George IV and William IV, whose short reign came between them, was born in 1819 making her younger than all but one of the Brontë siblings – only Anne Brontë, born in 1820, was born after Victoria.

By the time Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 Charlotte Brontë was twenty and her younger siblings were in their teens. By a happy coincidence, this was also the time that Emily and Anne Brontë composed their first jointly written diary paper, and we know from this that Victoria’s coronation had grabbed their attention, as we see from this extract:

“Tabby in the kitchin – the Emprerors and Empresses of Gondal and Gaaldine preparing to depart from Gaaldine to Gondal for the coranation which will be on the 12th of July. Queen Victoria ascended the throne this month.”

The coronation had so interested Emily and Anne that they created one of their very own in their youthful writings centred upon their imaginary kingdoms of Gondal and Gaaldine. These writings were always full of royal intrigue, of rebellions launched and thwarted, but these two youngest Brontë sisters never saw royalty themselves. The same cannot be said of their elder sister Charlotte.

Charlotte Brontë was in Brussels in 1842 and 1843 (with a brief return to Haworth in the former year after the death of her Aunt Elizabeth Branwell), and it was here that she saw Queen Victoria herself!

On 1st October 1843 Charlotte wrote from Brussels to her sister Emily Brontë in Haworth. In this letter Charlotte writes: “You ask about Queen Victoria’s visit to Brussels. I saw for her an instant flashing through the Rue Royale in a carriage and six, surrounded by soldiers. She was laughing and talking very gaily. She looked a little stout, vivacious Lady, very plainly dressed, not much dignity or pretension about her. The Belgians liked her very much on the whole. They say she enlivened the sombre court of King Leopold, which is usually as gloomy as a conventicle.”

When she later came to write her magnificent Belgian-set novel Villette it is surely this impression of Queen Victoria which inspired Charlotte’s description of the Queen of Labassecour?

“A signal was given, the doors rolled back, the assembly stood up, the orchestra burst out, and, to the welcome of a choral burst, enter the King, the Queen, the Court of Labassecour.

Till then, I had never set eyes on living king or queen; it may consequently be conjectured how I strained my powers of vision to take in these specimens of European royalty. By whomsoever majesty is beheld for the first time, there will always be experienced a vague surprise bordering on disappointment, that the same does not appear seated, en permanence, on a throne, bonneted with a crown, and furnished, as to the hand, with a sceptre. Looking out for a king and queen, and seeing only a middle-aged soldier and a rather young lady, I felt half cheated, half pleased.

Well do I recall that King – a man of fifty, a little bowed, a little grey: there was no face in all that assembly which resembled his. I had never read, never been told anything of his nature or his habits; and at first the strong hieroglyphics graven as with iron stylet on his brow, round his eyes, beside his mouth, puzzled and baffled instinct. Ere long, however, if I did not know, at least I felt, the meaning of those characters written without hand. There sat a silent sufferer – a nervous, melancholy man. Those eyes had looked on the visits of a certain ghost – had long waited the comings and goings of that strangest spectre, Hypochondria. Perhaps he saw her now on that stage, over against him, amidst all that brilliant throng. Hypochondria has that wont, to rise in the midst of thousands – dark as Doom, pale as Malady, and well-nigh strong as Death. Her comrade and victim thinks to be happy one moment – “Not so,” says she; “I come.” And she freezes the blood in his heart, and beclouds the light in his eye.

Some might say it was the foreign crown pressing the King’s brows which bent them to that peculiar and painful fold; some might quote the effects of early bereavement. Something there might be of both these; but these are embittered by that darkest foe of humanity – constitutional melancholy. The Queen, his wife, knew this: it seemed to me, the reflection of her husband’s grief lay, a subduing shadow, on her own benignant face. A mild, thoughtful, graceful woman that princess seemed; not beautiful, not at all like the women of solid charms and marble feelings described a page or two since. Hers was a somewhat slender shape; her features, though distinguished enough, were too suggestive of reigning dynasties and royal lines to give unqualified pleasure. The expression clothing that profile was agreeable in the present instance; but you could not avoid connecting it with remembered effigies, where similar lines appeared, under phase ignoble; feeble, or sensual, or cunning, as the case might be. The Queen’s eye, however, was her own; and pity, goodness, sweet sympathy, blessed it with divinest light. She moved no sovereign, but a lady – kind, loving, elegant.”

There was certainly plenty of elegance in the coronation of King Charles yesterday, and plenty of pomp and circumstance too, and in my opinion the Brontës would have loved every minute of it. I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post (whatever platform it’s on). Enjoy your bank holiday!