The nineteenth century could be a harsh time, diseases were rife and medical knowledge low, infant mortality was high, and the biggest killer of all was the poverty that gripped a large proportion of the population – a poverty that forced children into mines, up chimneys, and between the deadly machinery of automated looms. Even for those born into the lower middle class, life was unpredictable and dangerous, as we see in the Brontë novels. When we think of middle class Victorian patriarchs today we picture stern, hard hearted men. Not all were like that; Patrick Brontë was a kind, enlightened man (although prone to eccentricity and holder of a fiery temper), but there were real life Gradgrinds to be found – one who was well known to the Brontës, as we shall see in today’s post.

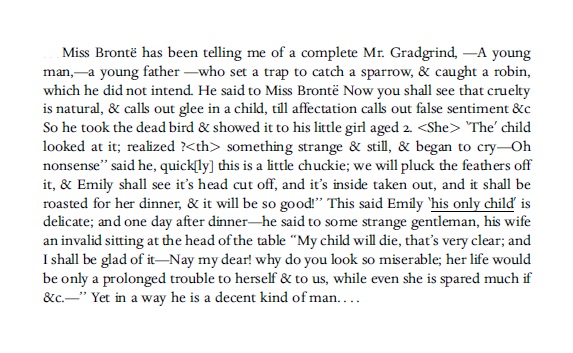

Thomas Gradgrind is the central character of Hard Times, a seminal novel by Charles Dickens first published in 1854 having been serialised throughout that year. He is a school board superintendent who sees profit as his primary concern in the running of schools, and life in general. Cold, hard facts are his currency, and emotions are an alien thing to him – at least at the beginning of the novel. With that in mind, we turn to an extract from a letter sent by Elizabeth Gaskell to John Forster on this day in 1854, in which we hear of Charlotte Brontë’s encounter with a real life Gradgrind:

Who could this awful man be? The clues are there. There was one young man very well known to Charlotte Brontë whose wife was in ill health and whose daughter was very sickly – his daughter named Emily. The man was Joseph Taylor, brother of her great friend Mary Taylor.

Members of the Taylor family are reproduced as the Yorkes of Briarmains in Charlotte’s second published novel Shirley, where Joe (Joseph) is the inspiration for Martin Yorke. The Taylors of Red House, Gomersal (that’s it at the head of this post) were once spectacularly wealthy as they held a monopoly on the production of red fabric used in military uniforms, and they even had their own bank. Peacetime brought a sudden cessation to their income, however, and the family dispersed – Mary herself emigrated to New Zealand and travelled widely across Europe.

Joe became a chemist, and he appears frequently in Charlotte Brontë’s correspondence, and there can be no doubt that she found him both fascinating and, at first, charming. In June 1843 Charlotte wrote to Ellen Nussey (who also knew the Taylors well) calling Joe, ‘worthy of being liked and admired also’. As she grew to know him better, however, she saw his cold, selfish side and her opinion of him became more moderated. By July 1852 she was referring to his (again in a letter to Ellen Nussey), ‘organ of combativeness and contradiction.’

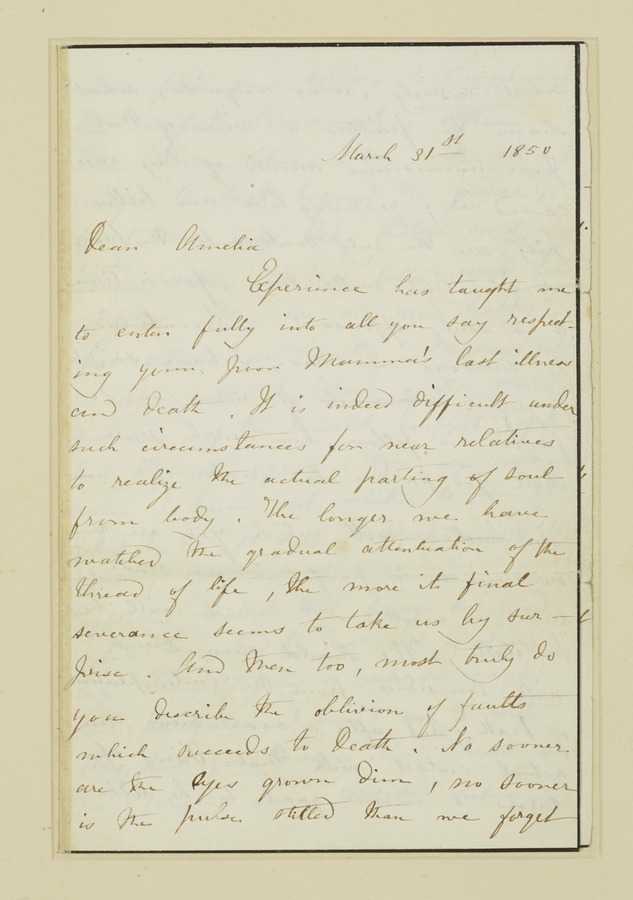

Joe Taylor became engaged to Amelia Ringrose, who had earlier been engaged to Ellen Nussey’s brother George. Charlotte immediately expressed sadness for Amelia whom she said was ‘caught between a coarse father and a cold, unsuiting lover.’ Charlotte commented further on this when she wrote that Joe was ‘imbued with selfishness and with a sort of unmanly absence of true value for the woman whose hand he seeks.’

They married in 1850 and had one child – a daughter they named Emily, although she was always called by her nickname of ‘Tim’. Tim was prone to frequent bouts of illness, something that the Gradgrind-ish Taylor saw as a weakness and a drain on his resources. In Hard Times, Thomas Gradgrind is forced to re-evaluate his ideals by the challenges faced by his children – their harsh, fact-centred upbringing has not made them better citizens, it has left them unable to cope with the real world they faced. So what happened to Joe Taylor?

As far as we know there was no such Damascene conversion for him. In fact, despite his reported contempt for the illnesses of his wife and daughter, they both outlived him. Joe Taylor died in 1857, and little Tim died a year later at the age of five. Amelia Taylor died in 1867, aged 48, and is buried in Wyke, a village near Bradford.

Joe Taylor was a complex person. Was he an outright villain, or was he, like Gradgrind, a man ground down by the conventions of his time and too determined to subdue his emotions. Despite his faults and his callous exterior, Charlotte after all described him as an essentially kindly man, and in 1854, the year of Elizabeth Gaskell’s letter, it was Joe Taylor whom Charlotte Brontë turned to to witness the marriage settlement between herself and Arthur Bell Nicholls.

I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post, and that times are not too hard for you and those you love.