The sun has risen, our once hydroptic earth has dried and warmed and greets us with a daily smile; these are long days full of opportunity, and so for many of us thoughts will be turning to holidays and excursions – if we aren’t already on one. Charlotte Brontë was on a working holiday in London on this week in 1851, and in today’s post we are going to look at two very different letters she sent on this day, 11th June, exactly 172 years ago.

Charlotte Brontë was in London as a guest of her publisher George Smith, staying at the grand family house at 112 Gloucester Square (which Charlotte incorrectly renders as ‘Gloucester Terrace’ in her letters). That’s it at the head of this post – Smith’s home has now been divided into a series of flats costing well in excess of a million pounds each. Whilst Charlotte was there Smith was determined to show her more of the delights that London had to offer, and he twice took her to the spectacle which was one of the greatest the city had ever seen, and which has gone down in history as a defining moment in this mid-Victorian period: the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace.

It’s fair to say that Charlotte was astonished by what she saw at the Crystal Palace, as we can see in a letter she wrote to her father Patrick Brontë:

“Yesterday I went for the second time to the Crystal Palace. We remained in it about three hours, and I must say I was more struck with it on this occasion than at my first visit. It is a wonderful place – vast, strange, new and impossible to describe. Its grandeur does not consist in one thing, but in the unique assemblage of all things. Whatever human industry has created you find there, from the great compartments filled with railway engines and boilers, with mill machinery in full work, with splendid carriages of all kinds, with harness of every description, to the glass-covered and velvet-spread stands loaded with the most gorgeous work of the goldsmith and silversmith, and the carefully guarded caskets full of real diamonds and pearls worth hundreds of thousands of pounds. It may be called a bazaar or a fair, but it is such a bazaar or fair as Eastern genii might have created. It seems as if only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from all the ends of the earth – as if none but supernatural hands could have arranged it this, with such a blaze and contrast of colours and marvellous power of effect. The multitude filling the great aisles seems ruled and subdued by some invisible influence. Amongst the thirty thousand souls that peopled it the day I was there not one loud noise was to be heard, not one irregular movement seen; the living tide rolls on quietly, with a deep hum like the sea heard from the distance.”

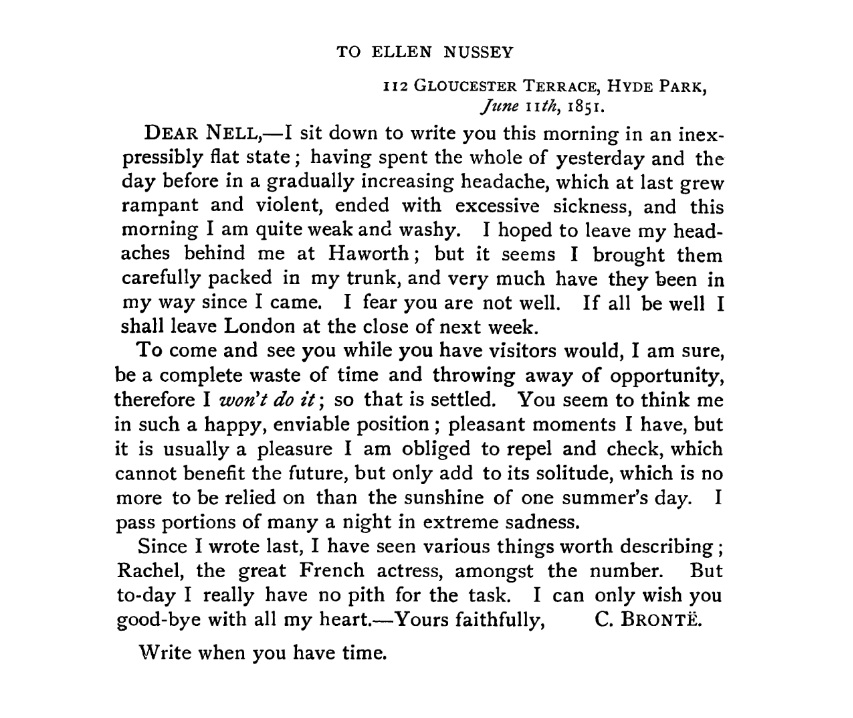

Typically for Charlotte, however, great excitement was followed by a great depression of spirits, as we see in the first of the letters she wrote today – to her great friend Ellen Nussey:

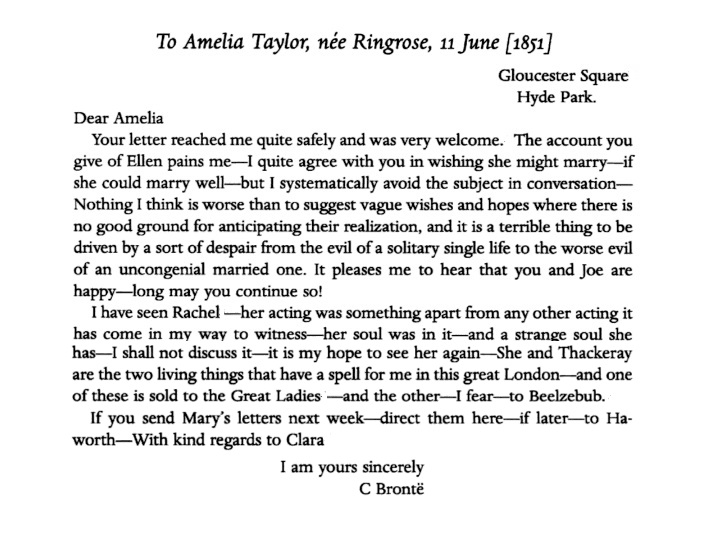

On this same day Charlotte also wrote to Amelia Taylor, formerly Amelia Ringrose before her ill fated marriage to Mary Taylor’s brother Joe. Here is Charlotte’s letter to Amelia:

In Charlotte’s letter to Amelia she gives a warning that a solitary single life can be terrible but an unhappy married life could be worse. Seemingly this is related to Ellen’s situation (Ellen, like Charlotte’s other great friend Mary Taylor, never married), but in reality I think Charlotte was addressing Amelia herself.

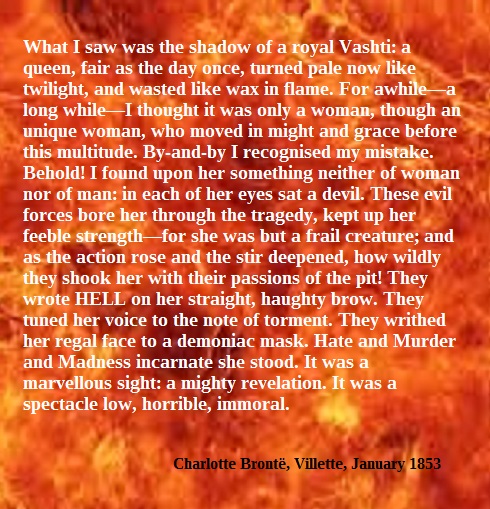

In Charlotte’s letter to Ellen we see the physical and mental effect that days of excitement in London have produced. There is one other thing constant in both letters: a reference to the French actress Rachel, albeit a brief one. Charlotte protests that she has not the energy or mood to give a full account of her view of Rachel – the then legendary actress (and courtesan) whose real name was Elisabeth Felix. She did, however, give us a description in two later letters. On 24th June 1851 she again wrote to Ellen after seeing Rachel on stage for a second time:

“On Saturday I went to hear and see Rachel; a wonderful sight – terrible as if the earth had cracked deep at your feet, and revealed a glimpse of hell. I shall never forget it. She made me shudder to the marrow of my bones; in her some fiend has certainly taken up an incarnate home. She is not a woman; she is a snake; she is the -”

These performances made a deep impression on Charlotte, for she was still writing of her in November, this time in a letter to the aforementioned Joe Taylor:

“Rachel’s acting transfixed me with wonder, enchained me with interest and thrilled me with horror. The tremendous power with which she expresses the very worst passions in their strongest essence forms an exhibition as exciting as the bull-fights of Spain and the gladiatorial combats of old Rome – and (it seemed to me) not one whit more moral than these poisoned stimulants to popular ferocity. It is scarcely human nature that she shews you; it is something wilder and worse; the feelings and fury of a fiend. The great gift of Genius she undoubtedly has – but – I fear – she rather abuses than turns it to good account.”

There is one more account of Rachel. So deep an impact had she made that Charlotte even included her in the novel Villette which she was working on at the time, under the name of Vashti. The descriptions of the actress character Vashti have more than a passing similarity to those given to Rachel in the letters above.

If you are on holiday today or later this year I hope it makes just as much an impression on you as Charlotte’s long 1851 sojourn in London did to her – but without the headaches. I also hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.