This day in 1848, also a Sunday, was a day of tragedy in Haworth Parsonage, a day of horror beginning to unfurl, for on this day Branwell Brontë died. He had been intermittently ill for a long time, but it wasn’t his addictions to opium, laudanum and alcohol that killed him. His death certificate gave the cause of death as ‘chronic bronchitis – marasmus.’ Marasmus was a wasting condition, a sign of what had truly killed him: tuberculosis. Within a year it would also claim the lives of Emily and Anne Brontë and turn the family home into a parsonage full of shadows, of memories, of faintly snatched ghosts.

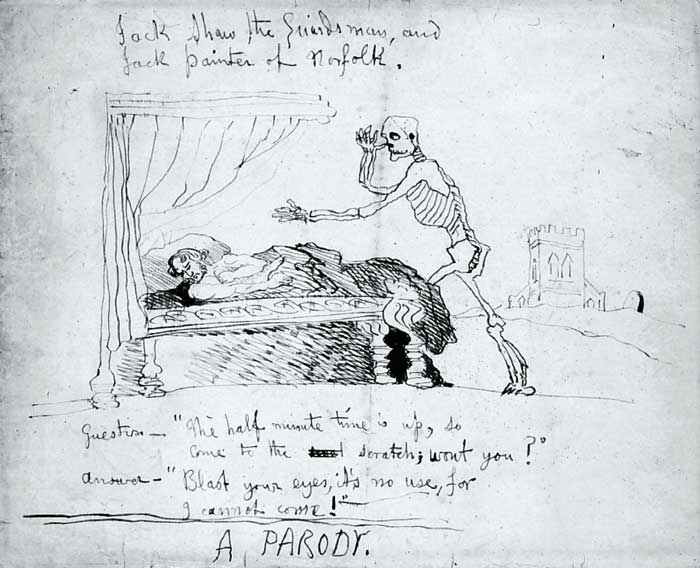

We’ve covered Branwell’s life before. It was a life of promise unfulfilled; he was, I believe, as his friend Francis Grundy so fittingly said, no domestic demon – he was simply a man moving in a fog, who lost his way. In today’s post we’re going to look at three accounts of Branwell Brontë and his death, starting with the account of his sister Charlotte Brontë. We know that on the day of his death, exactly 175 years ago today, he said ‘Amen’, rose from his bed, embraced his father and died.

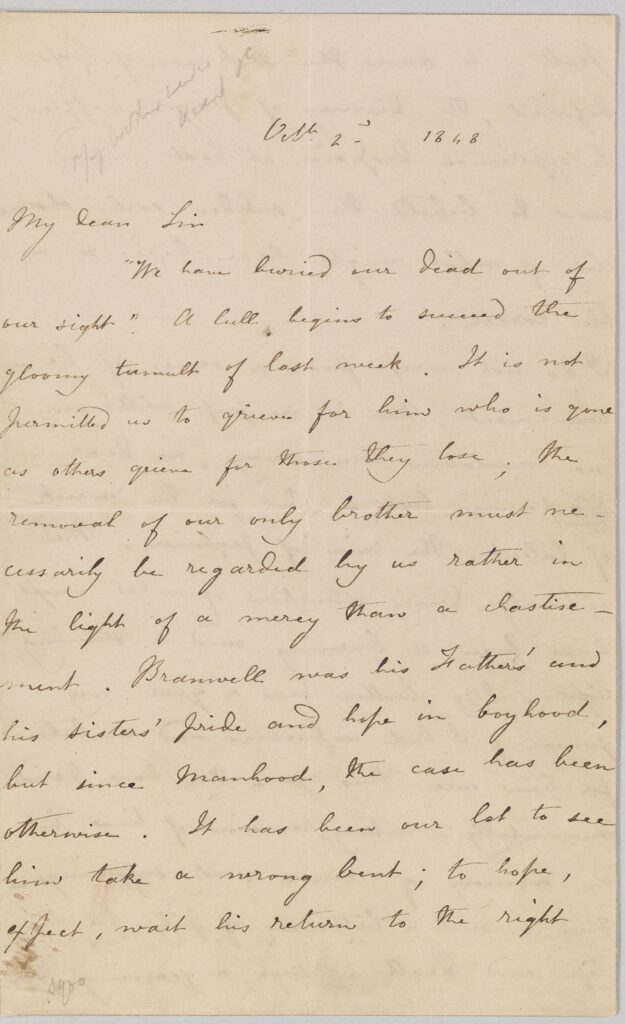

Charlotte’s letter to W. S. Williams, of her publisher Smith, Elder & Co, gives a moving account of her feelings after the death of her only brother – a brother she had loved dearly but then turned her back upon as his addiction and behaviour grew worse. Below you will see Charlotte’s actual letter, followed by a transcription below each page:

‘My dear Sir, “We have buried our dead out of our sight.” A lull begins to succeed the gloomy tumult of last week. It is not permitted us to grieve for him who is gone as others grieve for those they lose; the removal of our only brother must necessarily be regarded by us rather in the light of a mercy than a chastisement. Branwell was his Father’s and his sisters’ pride and hope in boyhood, but since Manhood, the case has been otherwise. It has been our lot to see him take a wrong bent; to hope, expect, wait his return to the right…’

‘path; to know the sickness of hope deferred, the dismay of prayer baffled, to experience despair at last; and now to behold the sudden early obscure close of what might have been a noble career.’

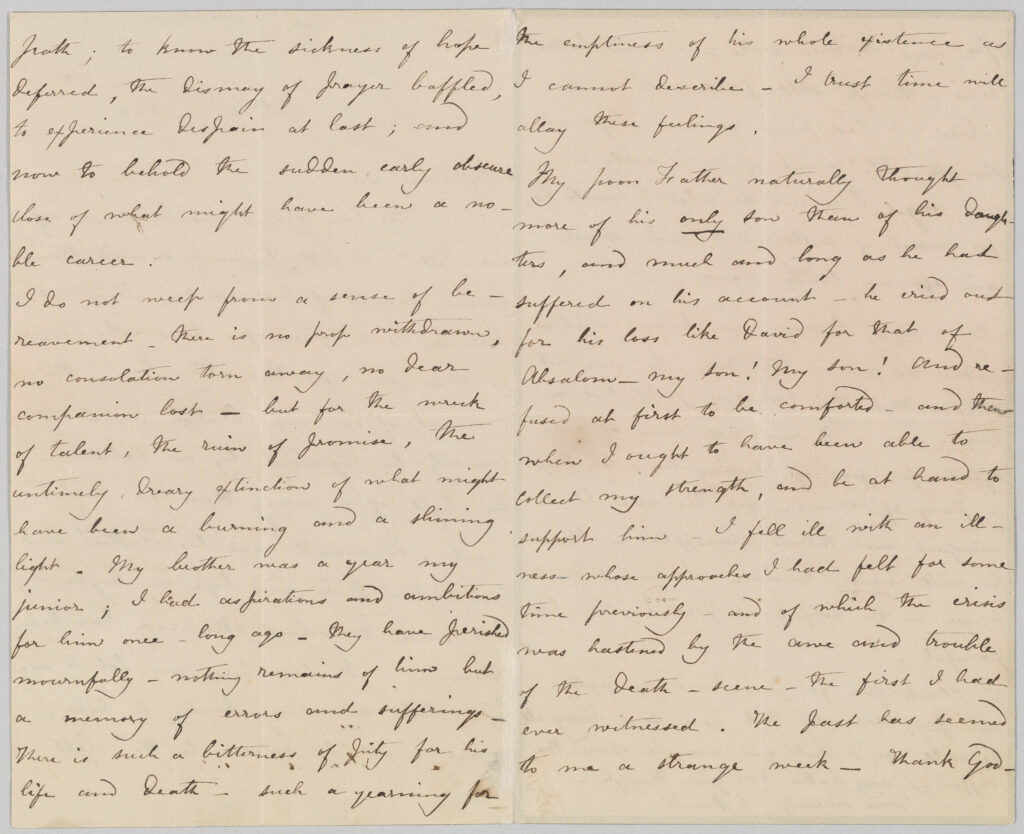

I do not weep from a sense of bereavement – there is no prop withdrawn, no consolation torn away, no dear companion lost – but for the wreck of talent, the ruin of promise, the untimely, dreary extinction of what might have been a burning and a shining light. My brother was a year my junior; I had aspirations and ambitions for him once – long ago – they have perished mournfully nothing remains of him but a memory of errors and sufferings – There is such a bitterness of pity for his life and death – such a yearning for the emptiness of his whole existence as I cannot describe – I trust time will allay these feelings.

My poor Father naturally thought more of his only son than of his daughters, and much and long as he had suffered on his account – he cried out for his loss like David for that of Absalom – My Son! My Son! And refused at first to be comforted – and then – when I ought to have been able to collect my strength, and be at hand to support him – I fell ill with an illness whose approaches I had felt for some time previously – and of which the crisis was hastened by the awe and trouble of the death-scene – the first I had ever witnessed. The past has seemed to me a strange week – Thank God –…’

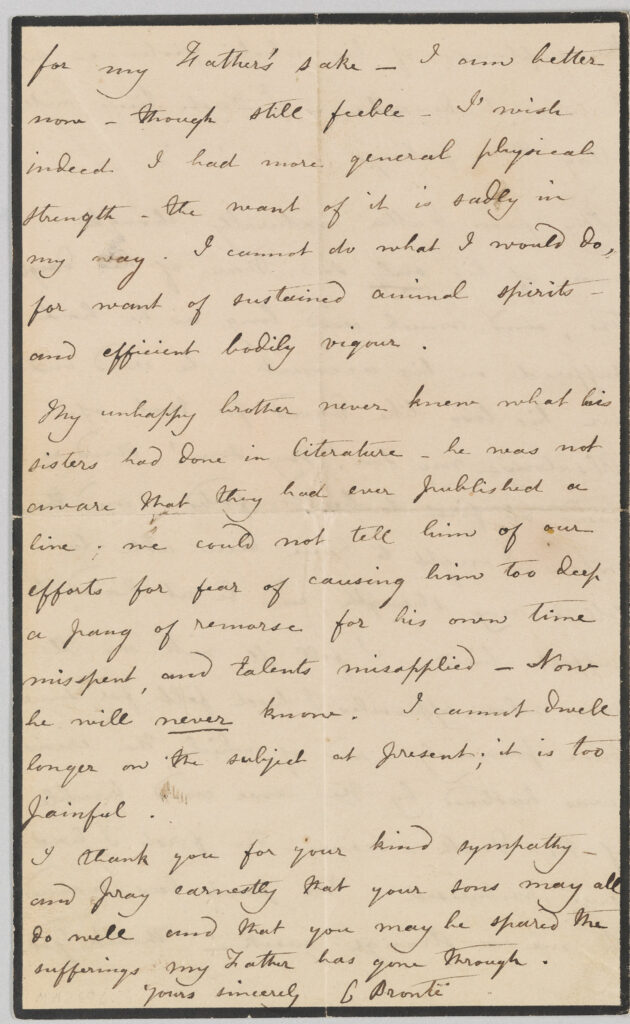

‘for my Father’s sake – I am better now – though still feeble – I wish indeed I had more general physical strength – the want of it is sadly in my way. I cannot do what I would do, for want of sustained animal spirits – and efficient bodily vigour.

My unhappy brother never knew what his sisters had done in literature – he was not aware that they had ever published a line; we could not tell him of our efforts for fear of causing him too deep a pang of remorse for his own time misspent, and talents misapplied – Now he will never know. I cannot dwell longer on the subject at present; it is too painful.

I thank you for your kind sympathy – and pray earnestly that your sons may all do well and that you may be spared the sufferings my Father has gone through. Yours sincerely, C Brontë’

Next we turn to an account from long-standing parsonage servant Martha Brown, given to Elizabeth Gaskell during a visit to Haworth Parsonage in this week 1843:

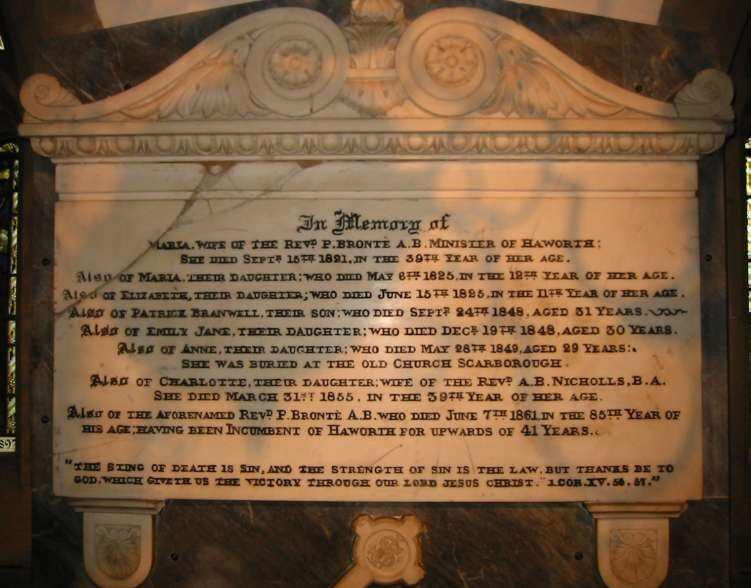

‘Patrick Branwell Brontë died Sep 24, 1848, aged 30. Emily Jane Brontë died Decr. 18. 1848 aged 29—Anne Brontë May 28, 1849, aged 27. ‘‘Yes!’’ said Martha. ‘They were all well when Mr. Branwell was buried;… about Mr. Branwell Brontë the less said the better – poor fellow. He never knew Jane Eyre was written although he lived for a year afterwards; but that year was passed in the shadow of the coming death, with the consciousness of his wasted life.’

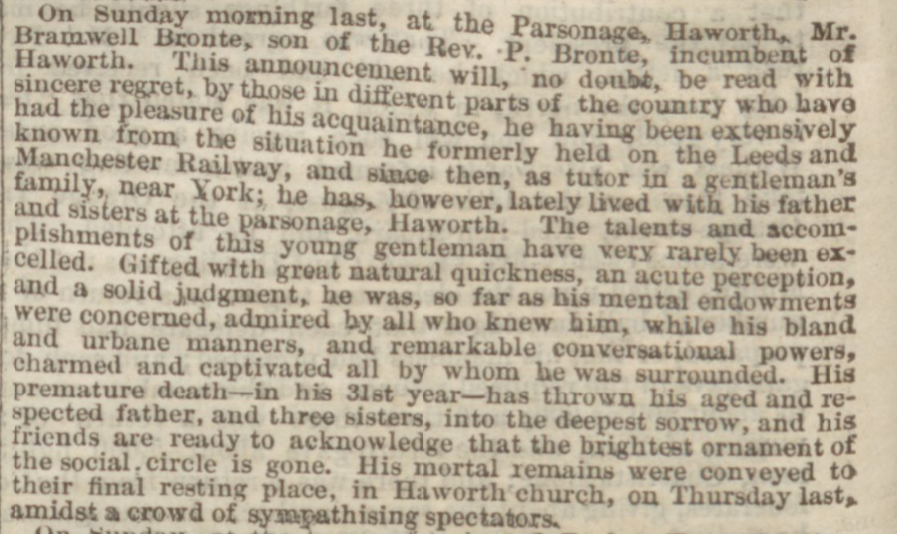

Finally we turn to the official obituary given to Branwell Brontë in the Leeds Times of 30th September 1848, and a fulsome and remarkable tribute it is too (despite them mis-spelling his name as Bramwell). For all his weaknesses and challenges, and his challenging behaviour, Branwell Brontë was loved by those who had known him.

I promised you a cheerier post this week, but this special anniversary would not permit it. On this very day in 1849, exactly a year after Branwell’s death, Charlotte Brontë sent a mournful letter, ending it, ‘Life is a battle – may we all be enabled to fight it well.’ I hope to see you next week for a new, and cheerier, Brontë blog post.