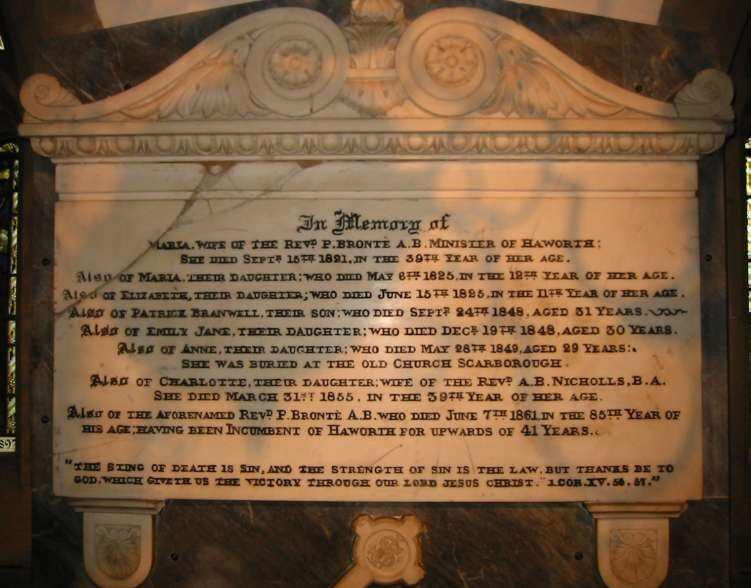

This week saw the anniversary of one of the great tragedies in the Brontë story, which is far from short of them of course. On 15th September 1821 Maria Brontë, nee Branwell, mother of the world’s most famous writing siblings died aged only 38. In today’s post we’re going to look at the impact this may have had on her youngest child, Anne Brontë.

On the anniversary, Friday, the Brontë Parsonage Museum’s social media declared: “On this day in 1821 Mrs. Brontë died in Haworth following a harrowing battle with cancer. Maria Brontë was survived by her husband, the Reverend Patrick Brontë, and their four surviving children Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë.”

I believe the medical evidence now pretty firmly shows that Maria did not die of cancer. In 1972 the Brontë Society’s journal published an in depth article by Professor Philip Rhodes, a Brontë fan and Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, Fellow of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and a Professor at the University of London’s St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School. He had studied all the evidence we had about the life and death of Maria Brontë and his conclusion was hard to disagree with:

“Mrs. Brontë died in September 1821. It seems that she had taken to her bed and had slowly succumbed to illness over the course of seven months. According to Mrs. Gaskell she was in agonising pain for most of this time, and this evidence is given on the strength of a letter from Mr. Brontë to his former vicar. Mrs. Brontë was born in 1783, so that at the time of her death she was only 38. The pain from which Mrs. Brontë suffered was presumably abdominal, and in view of her obstetric history it is probable that her symptoms were related to her pelvic generative organs. It is obvious that she did not die as an immediate result of her rapid childbearing, but probably because of some chronic disorder consequent upon it. The common causes of death during or just following childbirth are haemorrhage and infection. She could possibly have had a lingering chronic pelvic inflammation for this would be painful and debilitating and would cause heavy periods so that she would gradually become anaemic. Another possibility might have been a chronic inversion of the uterus giving rise to pain, bleeding and anaemia. The ultimate cause of death in both instances would be cardiac failure due to the anaemia. Of course there is an outside possibility of cancer of some organ within the abdomen, but it is unusual for this to occur before the age of forty. Certainly genital cancer would be very unlikely when the previous normality of reproductive function was so well displayed. There is no reference to vomiting so that a malady of the alimentary tract is less likely than some chronic disease of the pelvic organs. All in all, I would lean to to the idea of chronic pelvic sepsis together with increasing anaemia as the probable cause of her death. It is to be remembered that this was before the age of bacterial knowledge so that almost nothing was known of infectivity by extraneous organisms. Gynaecological knowledge was primitive, there was no ante-natal care and no attempt at follow-up after childbirth.”

Given that it would be hard to find a greater expert in the field than Professor Rhodes was I think we have to accept his prognosis that sepsis, rather than cancer, was the cause of Maria’s death.

The social media post made a rather more concrete error too, of course, as in September 1821 Maria left behind six surviving children not four. Let us not forget the two eldest Brontë siblings. Let us name them all now: Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Patrick Branwell, Emily Jane and Anne.

What impact did Maria’s tragic death have on her children? The greatest impact must inevitably have been felt by the oldest children at the time: Maria, named after her mother, would have been seven and Elizabeth Brontë six. Aged just seven, little Maria would now became a mother like figure to her five siblings. Perhaps this is one reason that she became such a precocious and advanced child, but alas Maria herself, and Elizabeth, had less than four years left to live.

Charlotte Brontë was just five at the time of her mother’s death, but she too was a highly intelligent and deep-feeling child. Even so, the memories she had of her mother began to fade over time, until Charlotte found it hard to remember what she had been really like at all. We can imagine how moving it must have been when, many years later, Patrick Brontë handed Charlotte, by then his only surviving child, the carefully preserved love letters Maria had sent him in 1812. Charlotte revealed in a letter the impact this moment had on her:

“It was strange now to peruse, for the first time, the records of a mind whence my own sprang; and most strange, and at once sad and sweet, to find that mind of a truly fine, pure, and elevated order… There is a rectitude, a refinement, a constancy, a modesty, a sense, a gentleness about them indescribable. I wish she had lived, and that I had known her.”

Anne Brontë was just one year old at the time of her mother’s death, so she would have had no recollection of her mother at all, and would have been incapable of understanding the scale of the loss at the time of Maria’s passing. Nevertheless, Anne was a deeply sensitive child and the atmosphere of mourning and despondency in late 1821 must have been felt by her.

For Anne especially a second mother was now to take to the stage. Elizabeth Branwell had made the long, and potentially perilous, journey to Haworth from Penzance (their Penzance home is shown at the head of this post) to nurse her sister Maria during her final illness. She could easily have returned to Cornwall after Maria’s death, but instead she remained in Haworth until her own death 21 years later.

Elizabeth became known as Aunt Branwell to the Brontë siblings, but she had sacrificed everything to step into a mother’s shoes and to do all she could to raise the children of the younger sister she had loved. To Anne especially she was like a mother, and the two shared a bedroom during Anne’s infancy and childhood. Ellen Nussey, great friend of Charlotte and the family as a whole, commented on this:

“Anne, dear, gentle Anne, was quite different in appearance from the others. She was her aunt’s favourite.”

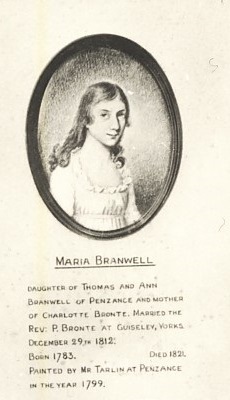

There are many potential reasons for this favouritism. Perhaps, understandably, Elizabeth Branwell felt particularly moved by the plight of this one year old girl left without a mother? Perhaps she particularly liked Anne’s quiet, studious nature and her love of the scriptures? But perhaps there is another clue in Ellen Nussey’s statement above? Anne was named after her maternal grandmother, the mother of Maria and Elizabeth. Perhaps she alone had also inherited the Branwell family looks? Take a look at this portrait of a young Maria Brontë drawn by a Cornish artist named Tonkins side by side with a portrait of a young Anne Brontë drawn by her sister Charlotte. I think there’s more than a passing similarity, so could it be that Anne in particular reminded Elizabeth Branwell of her dear, departed sister Maria?

In last week’s post we looked at another loss suffered by Anne Brontë – one she had to face in adulthood, and which changed the course of her writing and her life, the loss of her love William Weightman. Many of you have asked for a complete copy of the funeral sermon Patrick Brontë gave for his assistant curate Weightman, and I will be sending these out over the next couple of days.

Apologies too, for those of you who were unable to read last week’s blog. The WordPress gremlins struck yet again. You can guarantee to receive my weekly blogs by clicking the subscribe button, but I also hope that I will soon be able to overcome these problems by moving this website to a new platform. What is certain is that I will be here next Sunday with another new Brontë blog post, and it will be on a cheerier subject. After all, the world brings challenges to everyone, as the Brontës knew all too well, but it is still a magnificent world full of hope, opportunity and love. I hope you can join me then.