Exactly 181 years ago today an event happened which rocked Haworth Parsonage and changed the lives of the Brontë family forever, as well as changing the course of literary history forever too. On 29th October 1842, Elizabeth Branwell died. Known as Aunt Branwell to the Brontë siblings, she had become in reality a second mother to them after the tragic early death of their mother Maria, Elizabeth’s younger sister.

In 1821 Elizabeth had left behind a comfortable lifestyle and the warm climate of Penzance, Cornwall to travel 400 miles north to nurse her sister during her final illness; after Maria’s death she could have returned to the life and people she knew, but she remained in Haworth to help bring up her sister’s children and was to stay there for over 20 years until her own passing. The display cabinet at the top of this post shows some of Elizabeth’s belongings during her years in Haworth.

Elizabeth’s death was a drawn out painful one, seemingly caused by a strangulation of the bowel, and by her side throughout her final struggles was her nephew Branwell Brontë. He gave a moving account of her end, which shines a different light on perceptions of both those people. Branwell was a troubled adult, beset by mental health challenges and addictions to alcohol and opiates, but he clearly loved his family and certainly his aunt; Aunt Branwell, in turn, is often thought of as cold and austere by those who have heard no better, and yet Branwell Brontë painted a very different picture of her in two letters to his friend Francis Grundy, written before and after Elizabeth’s passing and which I have amalgamated into the following quote:

‘I have had a long attendance at the deathbed of the Rev. William Weightman, one of my dearest friends, and now I am attending at the deathbed of my aunt, who has been for twenty years as my mother. I expect her to die in a few hours… excuse this scrawl, my eyes are too dim with sorrow to see well… I am incoherent, I fear, but I have been waking two nights witnessing such agonising suffering as I would not wish my worst enemy to endure; and I have now lost the guide and director of all the happy days connected with my childhood.’

Perhaps Elizabeth Branwell’s guiding hand also helped Branwell cope with the demons which plagued him, for it was after her death that his behaviour declined.

There is another tribute to Elizabeth Branwell which came to light in this week in 1849. This week marks the anniversary of the publication of Shirley by Charlotte Brontë. I think it is a brilliant, yet all too often overlooked, novel. It’s composition was a traumatic one for Charlotte as she lost her sisters Emily and Anne (and her brother Branwell) during her writing of the novel. She has immortalised Emily as the titular Shirley and Anne as the real heroine of the novel Caroline.

We know from the account of Ellen Nussey that Anne Brontë was the favourite of Aunt Branwell – perhaps because she was a helpless one year old baby when her mother died. Anne subsequently shared a room with Elizabeth Branwell, and the aunt became a mother in all but title.

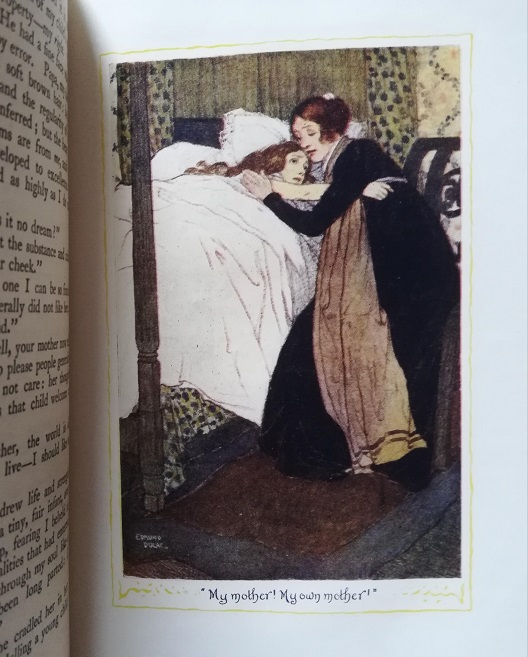

It is fitting then (spoiler alert if you haven’t yet read Shirley) that Caroline discovers that Mrs Pryor is in fact her real mother. Mrs Pryor is Charlotte’s tribute to Elizabeth Branwell, and one paragraph in particular is striking:

‘”Mamma, I am determined you shall not wear that old gown any more. Its fashion is not becoming; it is too strait in the skirt. You shall put on your black silk every afternoon. In that you look nice; it suits you. And you shall have a black satin dress for Sundays – a real satin, not a satinet or any of the shams. And, mamma, when you get the new one, mind you must wear it.”

“My dear, I thought of the black silk serving me as a best dress for many years yet, and I wished to buy you several things.”

“Nonsense, mamma. My uncle gives me cash to get what I want. You know he is generous enough; and I have set my heart on seeing you in a black satin. Get it soon, and let it be made by a dressmaker of my recommending. Let me choose the pattern. You always want to disguise yourself like a grandmother. You would persuade one that you are old and ugly. Not at all! On the contrary, when well dressed and cheerful you are very comely indeed; your smile is so pleasant, your teeth are so white, your hair is still such a pretty light colour. And then you speak like a young lady, with such a clear, fine tone, and you sing better than any young lady I ever heard. Why do you wear such dresses and bonnets, mamma, such as nobody else ever wears?”

“Does it annoy you, Caroline?”

“Very much; it vexes me even. People say you are miserly; and yet you are not, for you give liberally to the poor and to religious societies – though your gifts are conveyed so secretly and quietly that they are known to few except the receivers.”’

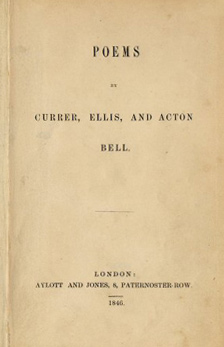

Here Caroline reveals Mrs Pryor’s habitual wearing of black clothing, and her secretive habit of helping those around us. Brontë friend Mary Taylor had criticised Elizabeth Branwell for always wearing old fashioned black clothing, and yet I feel she was doing that for the reason given above. She was spending her money not on herself, but on the Brontës and charitable causes. She it was who helped clear Patrick Brontë’s death after the death of his wife Maria, she it was who insisted on paying rent while she was in Haworth, she it was who paid for Charlotte and Emily to attend school in Brussels, and it was Aunt Branwell’s will which gave Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë the money to pay for the publication of their first book Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell.

On this day let us remember Elizabeth Branwell. She was a kind woman who placed family above any considerations of her own, and without her emotional and financial support it is quite probable that there would be no Brontë books today.

I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post, and watch out for ghosts, ghouls and things that go bump in the night on Tuesday!