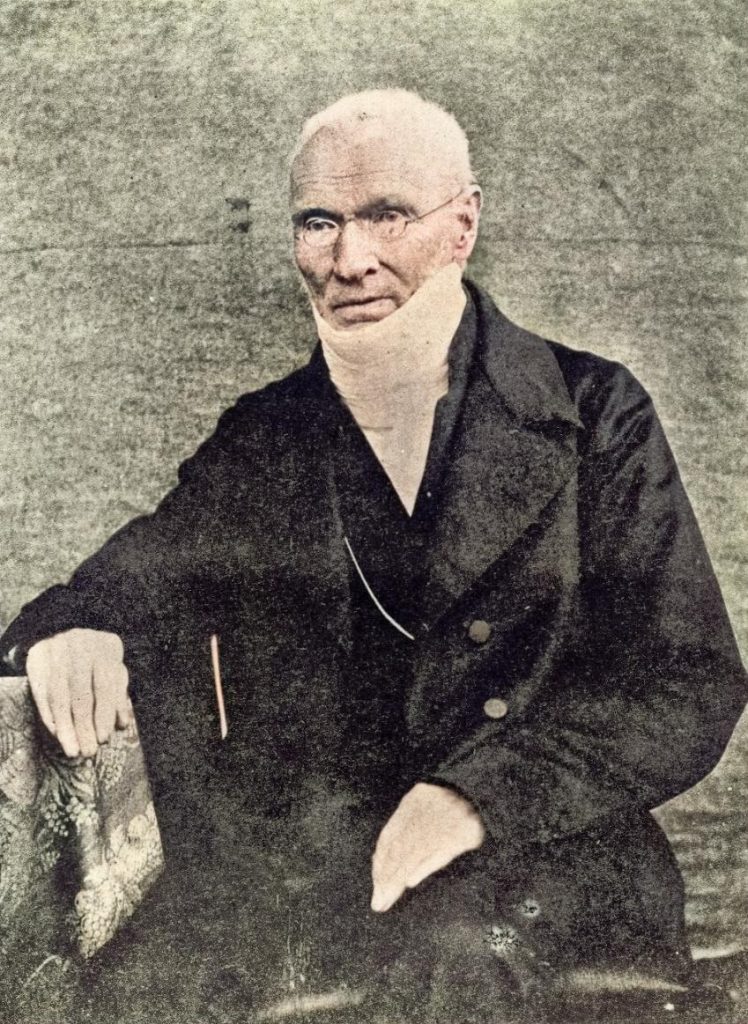

One of the greatest gifts you can give to a child, I feel, is encouraging their creativity. Whether they like painting, writing, or crafting, give their imaginations free reign and you’ll be amazed where it can lead. That’s one of the things we can thank Patrick Brontë for; unlike many fathers of the time he didn’t believe in censoring his daughter’s activities or reading matter – and, alongside his sister-in-law Elizabeth Branwell, he created an atmosphere within Haworth Parsonage where the children were free to play, to read, to learn, to create – and the results rock the world two centuries later.

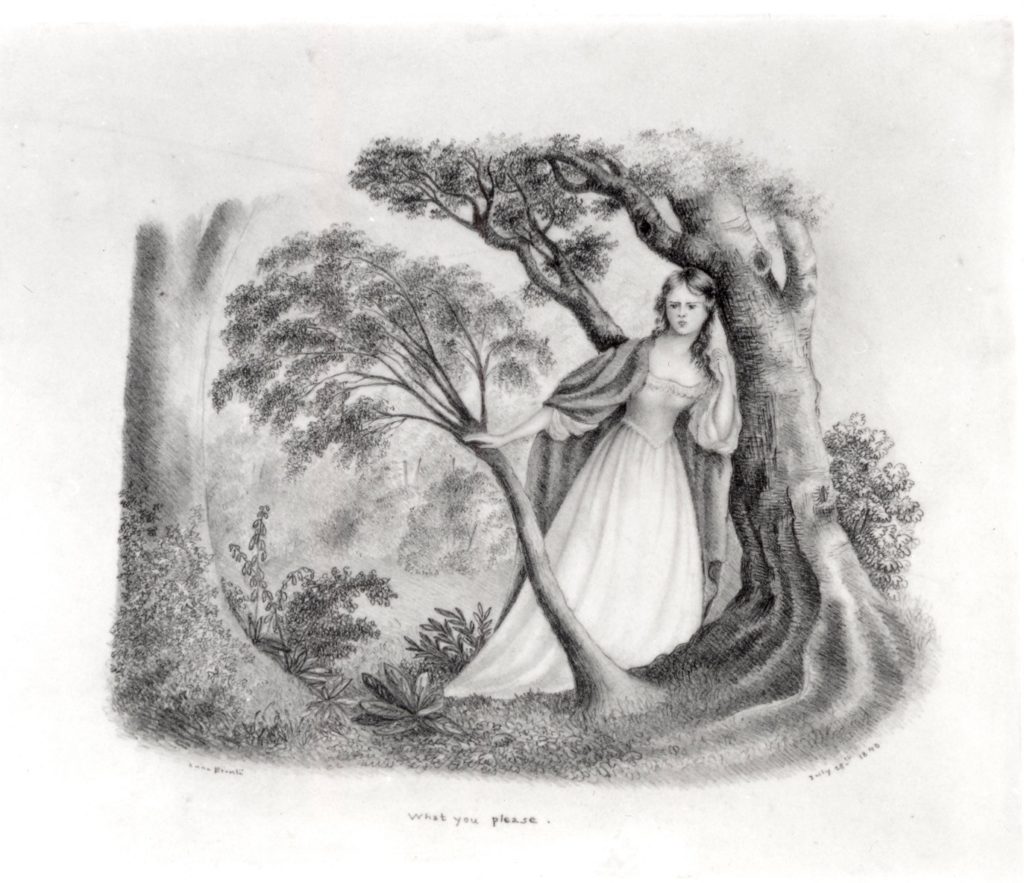

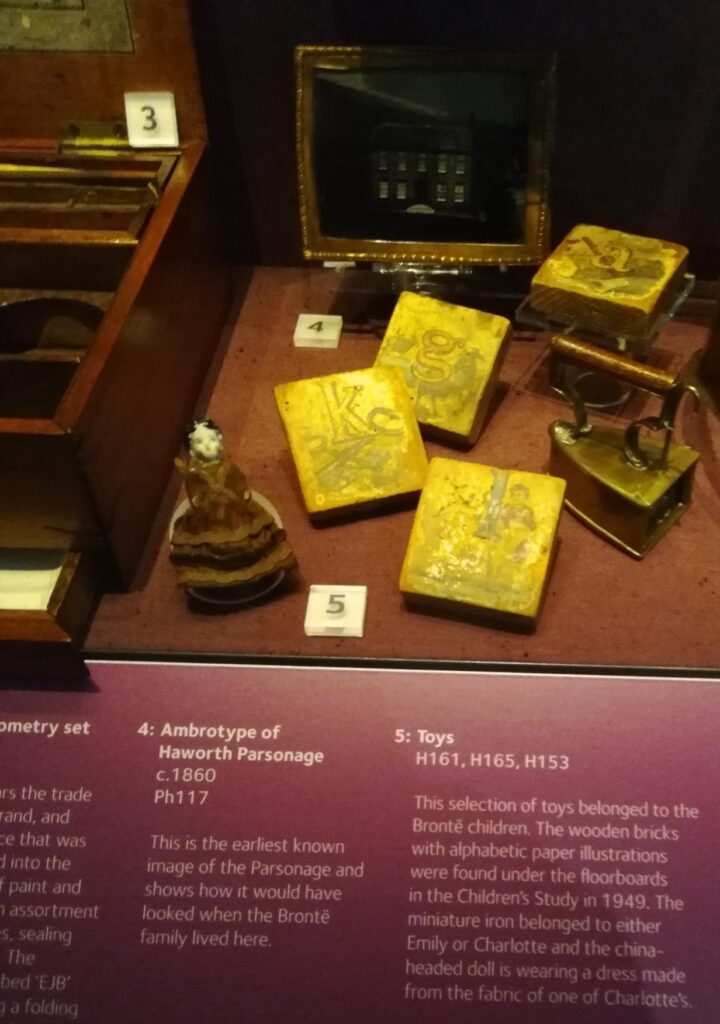

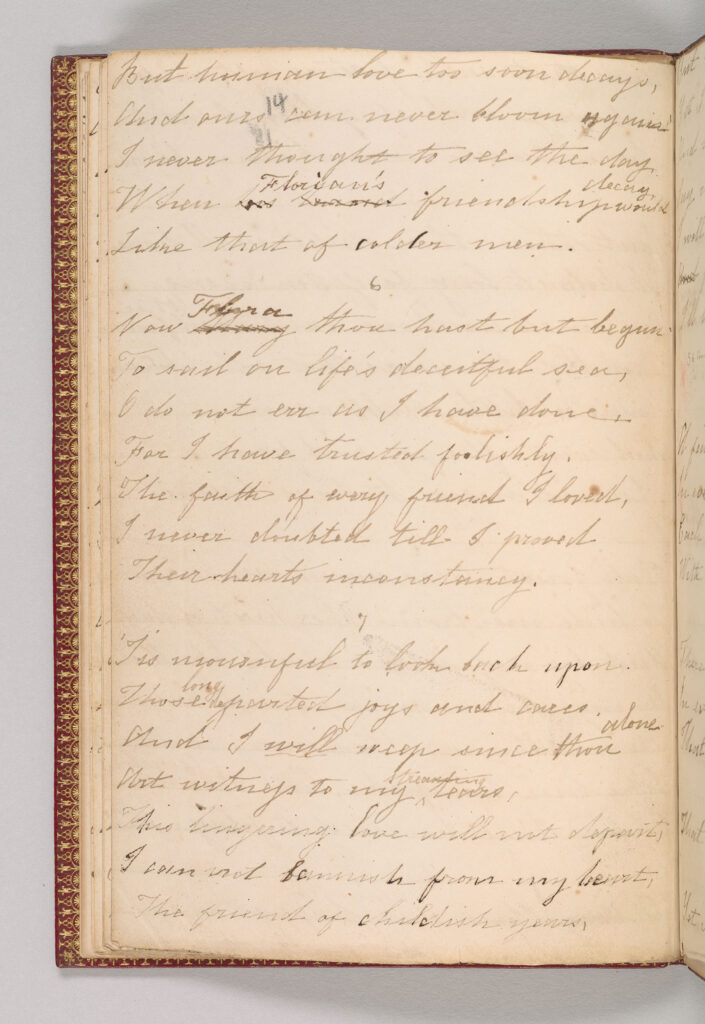

The first phase of Brontë creativity accompanied the invention of stories, then worlds, revolving around toy soldiers gifted to brother Branwell Brontë. They then invented plays, followed by the tiny books containing stories from their imaginary kingdoms of Angria and Gondal. Gondal was the domain favoured by twin-like sisters Emily and Anne Brontë, and the Gondalian output we still have exists in the form of poetry. In today’s new post we’re going to look at the earliest extant example of Anne Brontë’s poetry: “Verses By Lady Geralda.”

Yesterday, whilst looking through some of my own early school exercise books from the 1970s I found some of my own verse created aged 7 – including the rather freestyle example “Cat Cat” featured above. Perhaps it’s a good thing I eventually gravitated to the world of non-fiction rather than the world of poetry!

“Verses By Lady Geralda” is a rather accomplished poem, especially as Anne was just 16 at the time of its composition. It is set in the world of Gondal, and we can imagine Anne reading it to Emily as they discussed the latest developments in their kingdom. This then is the earliest writing we have of Anne Brontë, and from this little (if lengthy) acorn the mighty oaks of her mature poetry and novels grew!

Poetry is for everyone, whether they are seven or 107. It can bring calm at times of trouble, as Anne Brontë herself wrote, under the guise of Agnes Grey, when saying: “When we are harassed by sorrows or anxieties, or long oppressed by any powerful feelings which we must keep to ourselves, for which we can obtain and seek no sympathy from any living creature, and which yet we cannot, or will not wholly crush, we often naturally seek relief in poetry.”

This ability of poetry to soothe the mind, or bring clarity to the mind, is also at the heart of a system called Restorative Creativity which encourages self-care through creative writing. I think that’s something the Brontës would have had great sympathy with, and I myself have found it insightful and helpful. Simply reading great poetry, as well as embracing your own creativity, is also a very valuable and rewarding function of course. With that in mind, and with the hope that I’ll see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post, I leave you now with the young Anne Brontë’s “Verses By Lady Geralda”:

‘Why, when I hear the stormy breath

Of the wild winter wind

Rushing o’er the mountain heath,

Does sadness fill my mind?

For long ago I loved to lie

Upon the pathless moor,

To hear the wild wind rushing by

With never ceasing roar;

Its sound was music then to me;

Its wild and lofty voice

Made by heart beat exultingly

And my whole soul rejoice.

But now, how different is the sound?

It takes another tone,

And howls along the barren ground

With melancholy moan.

Why does the warm light of the sun

No longer cheer my eyes?

And why is all the beauty gone

From rosy morning skies?

Beneath this lone and dreary hill

There is a lovely vale;

The purling of a crystal rill,

The sighing of the gale,

The sweet voice of the singing bird,

The wind among the trees,

Are ever in that valley heard;

While every passing breeze

Is loaded with the pleasant scent

Of wild and lovely flowers.

To yonder vales I often went

To pass my evening hours.

Last evening when I wandered there

To soothe my weary heart,

Why did the unexpected tear

From my sad eyelid start?

Why did the trees, the buds, the stream

Sing forth so joylessly?

And why did all the valley seem

So sadly changed to me?

I plucked a primrose young and pale

That grew beneath a tree

And then I hastened from the vale

Silent and thoughtfully.

Soon I was near my lofty home,

But when I cast my eye

Upon that flower so fair and lone

Why did I heave a sigh?

I thought of taking it again

To the valley where it grew.

But soon I spurned that thought as vain

And weak and childish too.

And then I cast that flower away

To die and wither there;

But when I found it dead today

Why did I shed a tear?

O why are things so changed to me?

What gave me joy before

Now fills my heart with misery,

And nature smiles no more.

And why are all the beauties gone

From this my native hill?

Alas! my heart is changed alone:

Nature is constant still.

For when the heart is free from care,

Whatever meets the eye

Is bright, and every sound we hear

Is full of melody.

The sweetest strain, the wildest wind,

The murmur of a stream,

To the sad and weary mind

Like doleful death knells seem.

Father! thou hast long been dead,

Mother! thou art gone,

Brother! thou art far away,

And I am left alone.

Long before my mother died

I was sad and lone,

And when she departed too

Every joy was flown.

But the world’s before me now,

Why should I despair?

I will not spend my days in vain,

I will not linger here!

There is still a cherished hope

To cheer me on my way;

It is burning in my heart

With a feeble ray.

I will cheer the feeble spark

And raise it to a flame;

And it shall light me through the world,

And lead me on to fame.

I leave thee then, my childhood’s home,

For all thy joys are gone;

I leave thee through the world to roam

In search of fair renown,

From such a hopeless home to part

Is happiness to me,

For nought can charm my weary heart

Except activity.’