Today is a sad anniversary for Brontë lovers, as it marks the 175th anniversary of the death of Anne Brontë. The youngest of the six Brontë siblings was just 29 years old. Ellen Nussey recalled Anne’s final moments:

“She [Anne] still occupied her easy chair, looking so serene, so reliant: there was no opening for grief as yet, though all knew the separation was at hand. She clasped her hands, and reverently invoked a blessing from on high ; first upon her sister, then upon her friend, to whom she said, ‘Be a sister in my stead. Give Charlotte as much of your company as you can.’ She then thanked each for her kindness and attention. Ere long the restlessness of approaching death appeared, and she was borne to the sofa ; on being asked if she were easier, she looked gratefully at her questioner, and said, ‘It is not you who can give me ease, but soon all will be well through the merits of our Redeemer.’ Shortly after this, seeing that her sister could hardly restrain her grief, she said, ‘Take courage, Charlotte; take courage.’ Her faith never failed, and her eye never dimmed till about two o’clock, when she calmly and without a sigh passed from the temporal to the eternal. So still, and so hallowed were her last hours and moments. There was no thought of assistance or of dread. The doctor came and went two or three times. The hostess knew that death was near, yet so little was the house disturbed by the presence of the dying, and the sorrow of those so nearly bereaved, that dinner was announced as ready, through the half-opened door, as the living sister was closing the eyes of the dead one.”

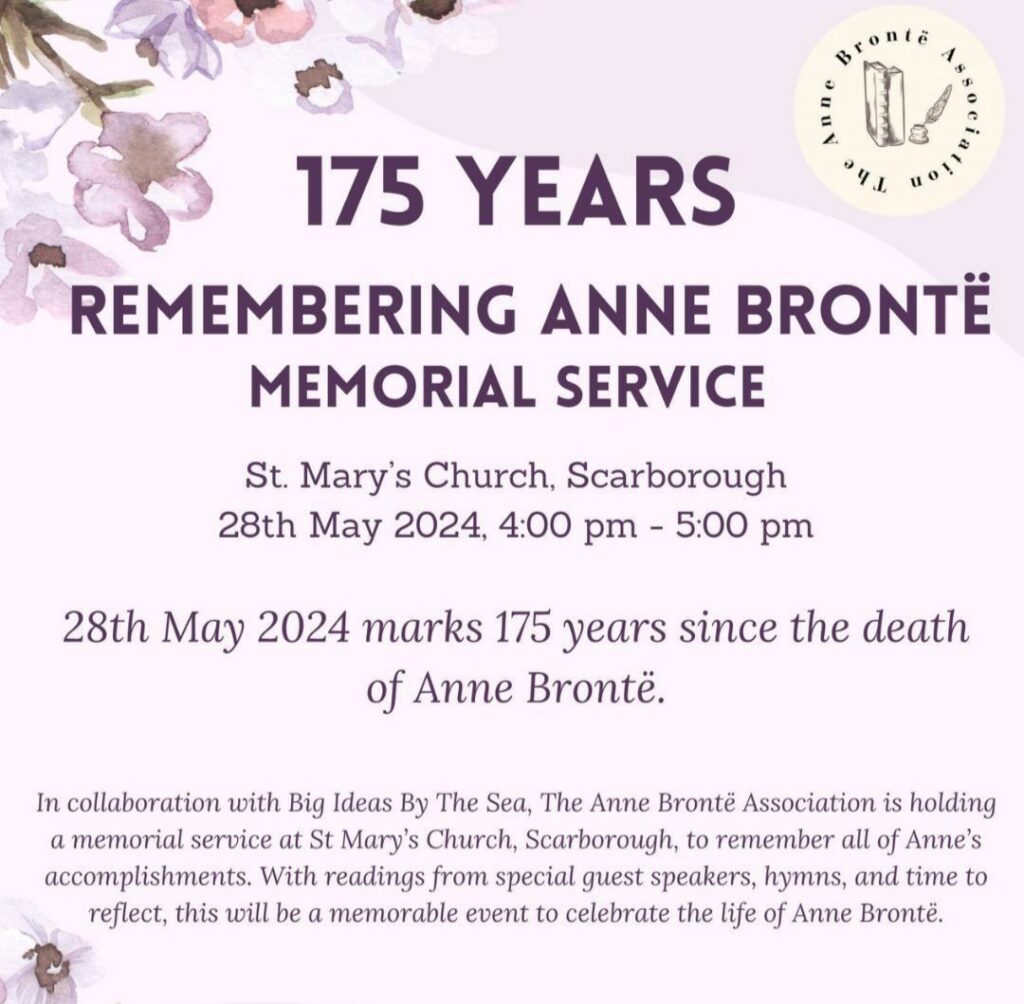

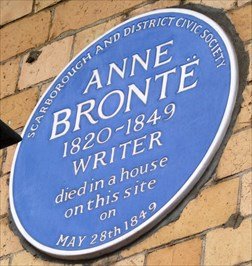

Anne Brontë died on 28th May 1849 on the site of what is now the Grand Hotel, Scarborough. It was a location she loved, and she rests eternally in the churchyard of St. Mary’s church, in the shadow of Scarborough Castle. She will be remembered today in a memorial service at the self same church, and by literature lovers across the globe. Anne could never have imagined that her name would live on 175 years after her passing, but she was always a modest woman more concerned with the message she was imparting than in any fame or reward for herself.

I’m often asked just why Anne Brontë is my favourite Brontë sister. I love Charlotte and Emily too, of course, but for me it will always be Anne that holds a special place in my heart. Perhaps it is because she is the underdog, with her work unfairly neglected when compared to her more famous older sisters? I was once asked in a pub quiz ‘Who is the least famous Brontë sister?’ and, because I wanted to win, I had to give the answer I knew they would be looking for: Anne. Of course, the correct answer would be Maria or Elizabeth. The good news is that I think Anne is finally starting to get the reputation she deserves. More and more people are acknowledging that Anne Brontë deserves to be counted amongst the very top tier of British writers.

I also love Anne because her work manages to be both serious and humorous. Anne herself put it perfectly in her preface to the second edition of The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall:

“I love to give innocent pleasure. Yet, be it understood, I shall not limit my ambition to this or even to producing a perfect work of art: time and talents so spent, I should consider wasted and misapplied. Such humble talents as God has given me I will endeavour to put to their greatest use; if I am able to amuse, I will try to benefit too; and when I feel it my duty to speak an unpalatable truth, with the help of God, I will speak it, though it be to the prejudice of my name and to the detriment of my reader’s immediate pleasure as well as my own.”

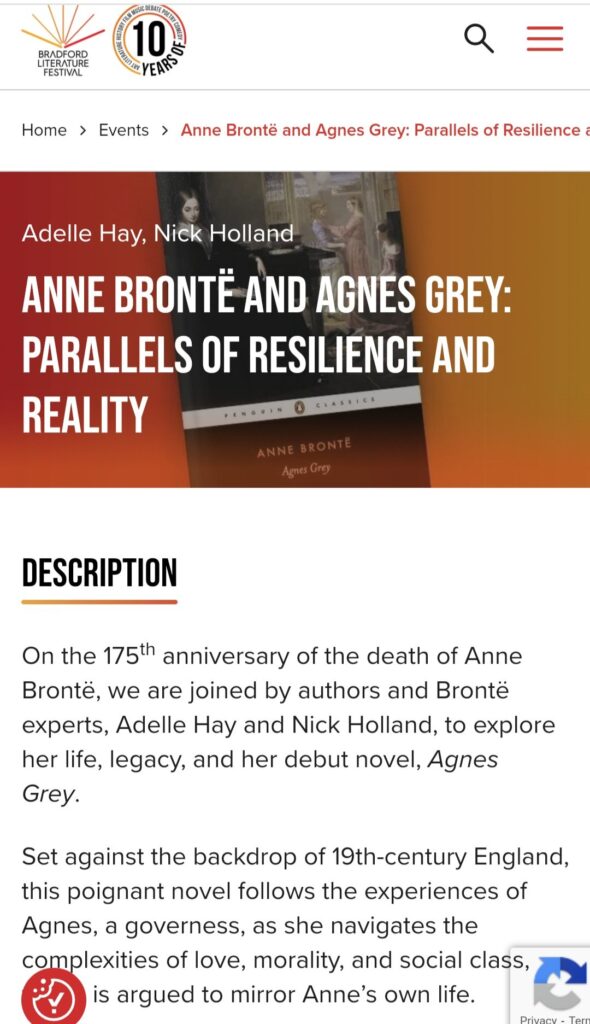

Anne succeeded admirably in creating important works of literature that convey important messages. The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall was perhaps the first novel to set before readers the horrors of abusive marriages, the terror of addiction, the inequality between sexes and social classes, and the hypocrisy of organised religion and society at the time. This was an incredibly brave thing for Anne to do, and her incredible novel is as powerful and relevant today as it was in 1848. And yet, it still manages to entertain, to provide innocent pleasure – just as her wonderful debut novel Agnes Grey does.

Above all, it’s clear when we look at Anne’s life, as I have been privileged to do in two biographies and within this blog, that she was a kind, loving and compassionate woman. She adored animals, loved nature, and was religious without ever being judgmental. Anne was incredibly shy, yet she overcame this and made her way in life: she did, after all, hold down a job for more than five years, which was a far greater period than any of her siblings managed. She was a genius writer and a first class human being who had all the tools she needed to succeed in life – except one. She didn’t have time.

Anne died far too young, and her passing has surely left us without what would have been a succession of wonderful books. We can and should, therefore, treasure the novels and poetry Anne has loved us.We should also look at Anne’s life, and her passing, and remember that life is short, we never know what is waiting for us, so we must do all we can to use the talents we have to their fullest.

I leave you with Charlotte Brontë’s tribute to her youngest sister Anne, written during her time of mourning. Anne Brontë left this world 175 years ago today, but in a way she will never leave us whilst her books are still being read and enjoyed. Thank God for Anne Brontë.

“There’s little joy in life for me,

And little terror in the grave;

I’ve lived the parting hour to see

Of one I would have died to save.

Calmly to watch the failing breath,

Wishing each sigh might be the last;

Longing to see the shade of death

O’er those belovèd features cast.

The cloud, the stillness that must part

The darling of my life from me;

And then to thank God from my heart,

To thank Him well and fervently;

Although I knew that we had lost

The hope and glory of our life;

And now, benighted, tempest-tossed,

Must bear alone the weary strife.”