There were some similarities in both the life and work of Charlotte and Anne Brontë, beyond the fact that they were sisters of course. Both wrote books whose eponymous heroine was a governess: Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey, and both worked as a governess – although Anne’s nearly six years in service to the Robinson and Ingham families was much longer than the brief periods Charlotte spent as a governess to the White family of Rawdon and the Sidgwick family of Stone Gappe. Charlotte stayed in that job for less than two months, but as we shall see in today’s post it was a time which greatly influenced her most acclaimed novel.

Stone Gappe is an early 18th century mansion near Lothersdale in North Yorkshire, ten miles from Haworth. Charlotte became governess there in May 1839, her first attempt at being a governess. Her employees were the Sidgwick family who employed Charlotte to teach their young children, but she found this a far from enjoyable role – as we see in a letter she wrote exactly 185 years ago this weekend. The letter, sent by Charlotte to sister Emily Brontë (referred to affectionately by Charlotte as ‘Lavinia’), is reproduced below:

The letter starts promisingly, the hall is divine and the grounds are divine – and still are, by the way, if you ever get the chance to visit this Grade II* listed building. It is an area which delights Charlotte’s senses, but she has not a moment to enjoy it and her time is spent endlessly sewing and darning and looking after the children from hell. Alack-a-day indeed, as Charlotte so charmingly puts it! There is one portion of the letter which is particularly striking to one who is reading it with nearly two centuries worth of hindsight:

“I see now more clearly than I have ever done before that a private governess has no existence, is not considered as a living and rational being except as connected with the wearisome duties she has to fulfil.”

Surely we see a glimpse of Jane here, and in the only solace that Charlotte gets from her despondency – time spent with the taciturn, yet kind, master of the house. He is a vision of Charlotte’s ideal, older, plain speaking, wealthy – a man who strides ahead with a great big dog by his side: “It is very seldom that he speaks to me, but when he does I always feel happier and more settled.”

The master of Stone Gappe was John Benson Sidgwick, a wealthy mill owner. Born in 1800 he was sixteen years older than Charlotte, and had made vast sums of money from owning High Mills in Skipton at a time when the industrial revolution was beginning to boom. He and his family spent summers at Stone Gappe and wintered at Skipton Castle.

At this very same time Anne Brontë too was working as a governess to the family of a wealthy industrialist – to the Ingham family of Blake Hall in Mirfield. Anne found that her charges were ill educated, unruly and often downright violent – but she turned this experience to good use by recreating the family as the monstrous Bloomfield family.

Charlotte too found that her children had a tendency towards spontaneity of the violent kind. Although not mentioned in her letter we know, very revealingly, that one of the children – a Benson Sidgwick threw a Bible at Charlotte’s head! We know this from a memoir by an A. C. Benson of his father Archbishop Edward Benson of Canterbury – who was in turn a cousin of John Benson Sidgwick. In it, he tells the story of Charlotte’s Stone Gappe sojourn from the Sidgwick point of view:

“Charlotte Brontë acted as governess to my cousins at Stone Gappe for a few months in 1839. Few traditions of her connection with the Sidgwicks survive. She was, according to her own account, very unkindly treated, but it is clear that she had no gifts for the management of children, and was also in a very morbid condition the whole time. My cousin Benson Sidgwick, now vicar of Ashby Parva, certainly on one occasion threw a Bible at Miss Brontë! and all that another cousin can recollect of her is that if she was invited to walk to church with them, she thought she was being ordered about like a slave; if she was not invited, she imagined she was excluded from the family circle. Both Mr. and Mrs. John Sidgwick were extraordinarily benevolent people, much beloved, and would not wittingly have given pain to any one connected with them.”

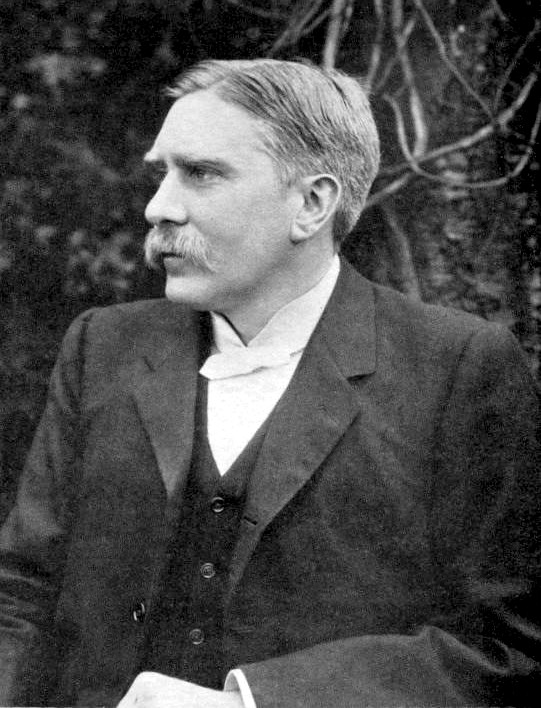

An interesting but not unbiased account from A. C. Benson there; perhaps his most lasting legacy is a rather different piece of writing – he was the man who wrote the lyrics to Edward Elgars ‘Land Of Hope And Glory.’ His brother Edward also found fame, as author of the Mapp and Lucia novels.

Charlotte was governess at Stone Gappe for a few short weeks, but the repercussions are still being felt by readers across the globe today. It is said that the Stone Gappe building is the model for Gateshead Hall where young Jane Eyre is raised. Jane has a book thrown at her by her cousin, just as Charlotte had a book thrown at her during her time there. And in Charlotte’s depiction of John Benson Sidgwick we get an early glimpse of a Rochester-like character.

Charlotte used her time as a governess to great effect in her writing – and Anne Brontë did exactly the same, which is why her novel Agnes Grey is so autobiographical in many places – this is exactly the topic I will be discussing at the Bradford Literature Festival on Sunday 7th July at 1 pm. You can buy tickets at this link, and it would be great to see you there!

It would also be great to see you right here next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post – may the week ahead be a sunnier one for you.