Pop singers and groups are often wary of second album syndrome – will their second offering live up to the expectation generated by the success of their first? That’s not confined to modern music of course, for Charlotte Brontë must have been feeling second novel syndrome on this week in 1849. In today’s post we’ll look at the publication of Shirley.

Shirley was published on 26th October 1849 making it the second published novel by Charlotte Brontë – although it was her third written novel, The Professor was only published posthumously. Charlotte, who was still using the pseudonym of Currer Bell, could never have guessed the success that Jane Eyre enjoyed. Within weeks of her sending her manuscript to Smith, Elder and Co. it had been published, was in shops, and was selling at a ferocious rate. Her publishers were understandably keen to have a second novel by this hot author, but they would have to wait for over two years.

A succession of tragedies delayed Charlotte’s production of this second novel, as her brother Branwell and her sisters Emily and Anne all died, at far too early an age, during its composition. After Anne’s death in May 1849 Charlotte found it hard to continue with Shirley, but eventually she found solace in creativity, and she gave the novel its most moving moments: Caroline, who is clearly based upon Anne Brontë, is dying of a condition reminiscent of tuberculosis:

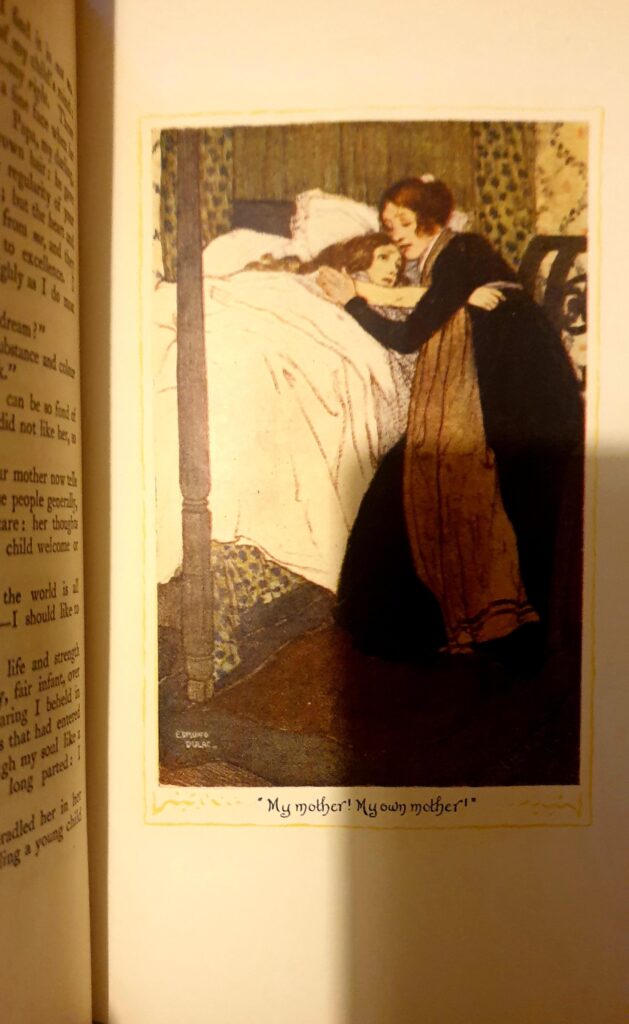

“Not always do those who dare such divine conflict prevail. Night after night the sweat of agony may burst dark on the forehead; the supplicant may cry for mercy with that soundless voice the soul utters when its appeal is to the Invisible. ‘Spare my beloved’, it may implore. ‘Heal my life’s life. Rend not from me what long affection entwines with my whole nature. God of heaven, bend, hear, be clement!’ And after this cry and strife the sun may rise and see him worsted. That opening morn, which used to salute him with the whisper of zephyrs, the carol of skylarks, may breathe, as its first accents, from the dear lips which colour and heat have quitted, ‘Oh! I have had a suffering night. This morning I am worse. I have tried to rise. I cannot. Dreams I am unused to have troubled me.’

Then the watcher approaches the patient’s pillow, and sees a new and strange moulding of the familiar features, feels at once that the insufferable moment draws nigh, knows that it is God’s will his idol shall be broken, and bends his head, and subdues his soul to the sentence he cannot avert and scarce can bear.”

In real life Charlotte had to watch this happen with Anne, all her prayers and supplications could not save her – but in the novel, she would prevail. Miraculously Caroline recovers. It’s believed that initially it was intended that Caroline would die in the novel, but real life events made Charlotte change the narrative: she could not save Anne in reality, but she could save her in fiction. This, along with her depiction of people and places she knew in the novel, is one reason I love Shirley. I think it’s as good as any of Charlotte Brontë’s novels, but what would the critics think?

On 4th October 1849 Charlotte wrote to her publisher George Smith:

“The thought that Shirley has given pleasure at Cornhill [the headquarters of her publisher] yields me much quiet comfort. No doubt however you are – as I am – prepared for critical severity – but I have good hopes the vessel is sufficiently sound of construction to weather a gale or two, and make a prosperous voyage for you in the end.”

On 24th October, Charlotte again wrote to Smith:

“I am glad Shirley is so near the day of publication, as I know and then feel anxious to know its doom and to learn what sort of reception it will get. In another month some of the critics will have pronounced their fiat – and the Public also will have evinced their mood towards it. Meanwhile – patience.”

In fact Shirley gained mostly positive reviews – except for one review in The Times newspaper. Its reviewer said: “Shirley is at once the most high-flown and the stalest of fictions.” This pronouncement reduced Charlotte Brontë to tears. Then, as now, there were critics and commentators out there who were only too eager to tear down those who had been successful, but both author and novel have now a fame and reputation that those envious critics could never claim.

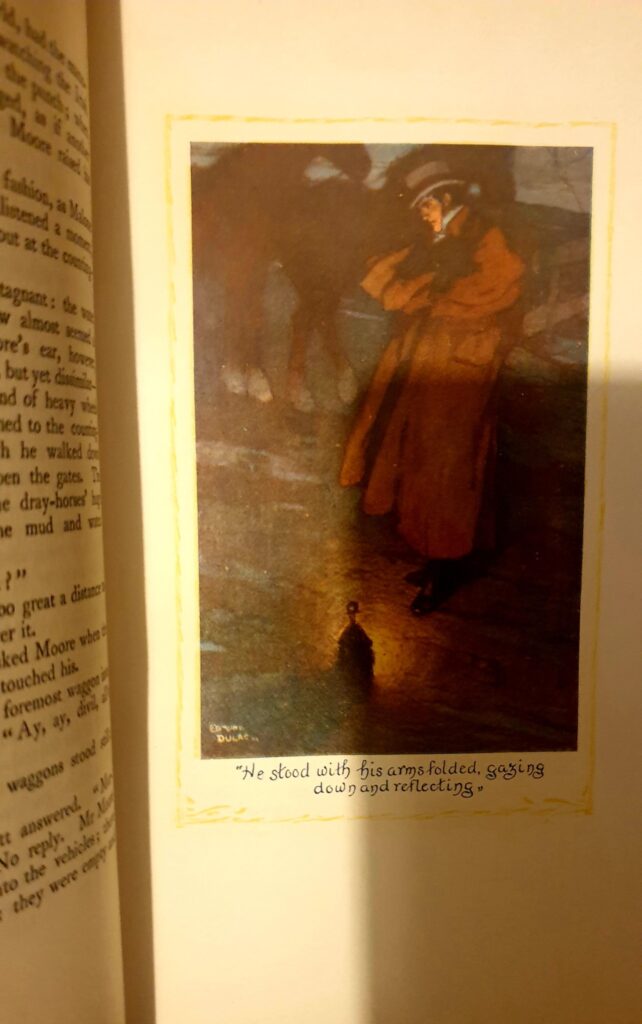

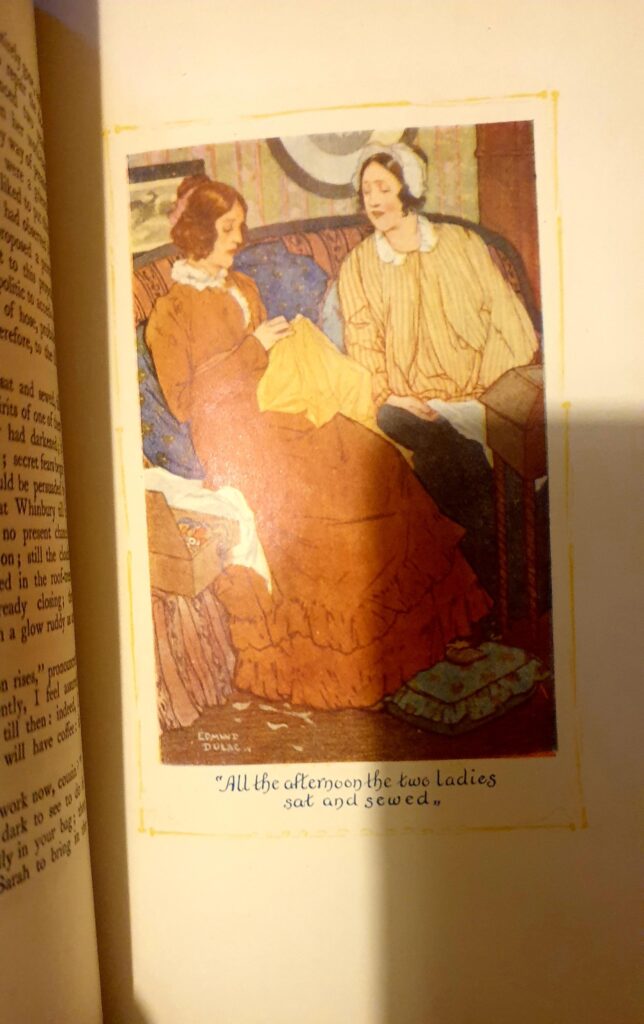

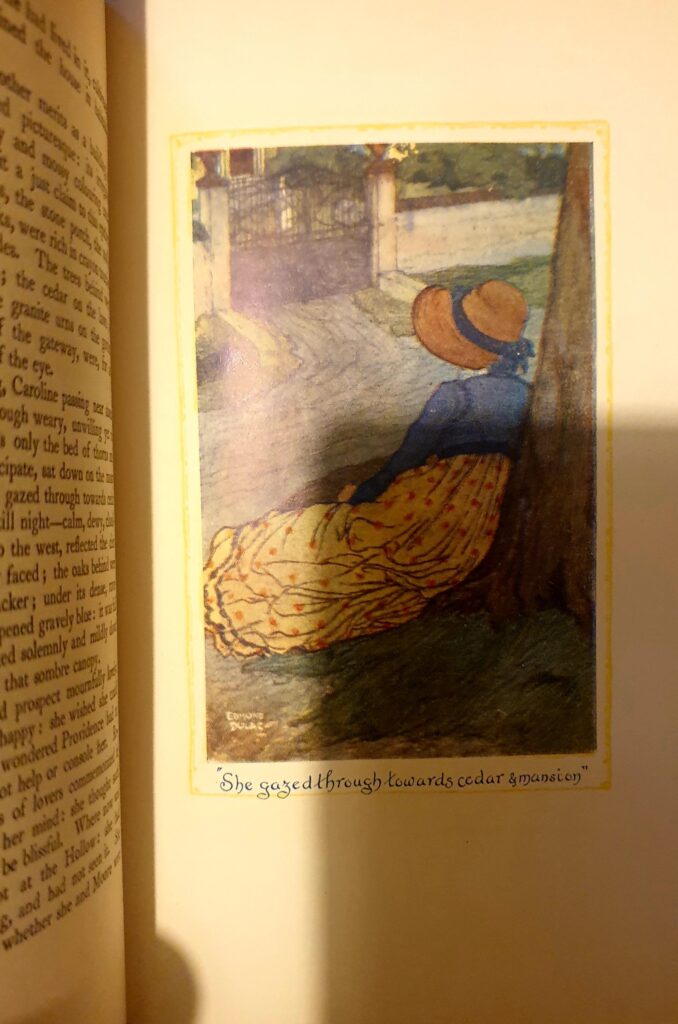

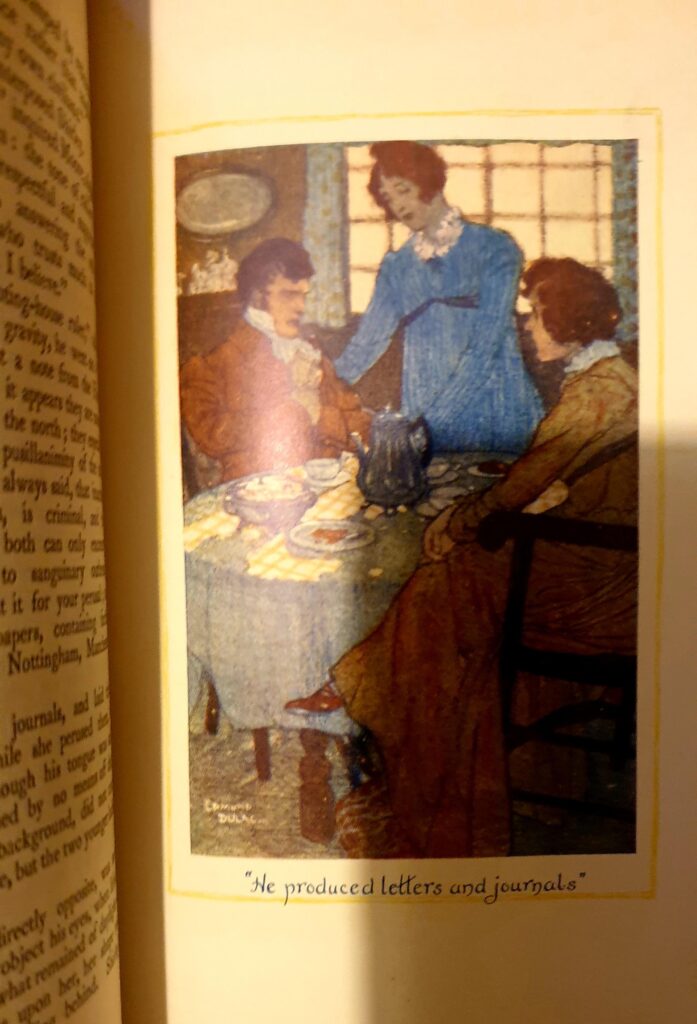

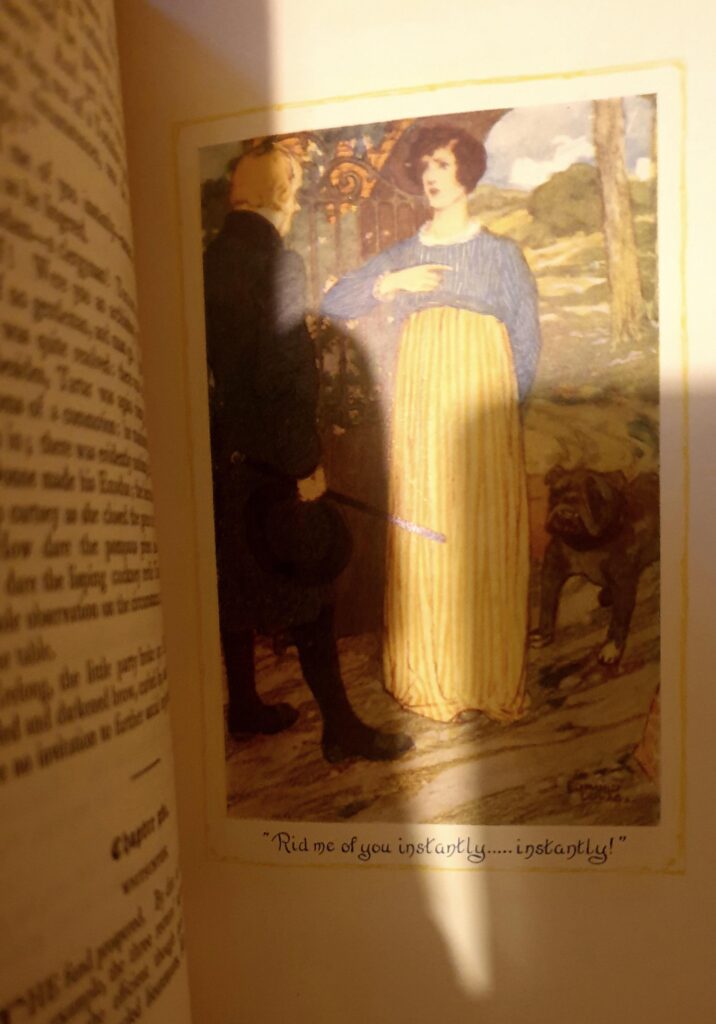

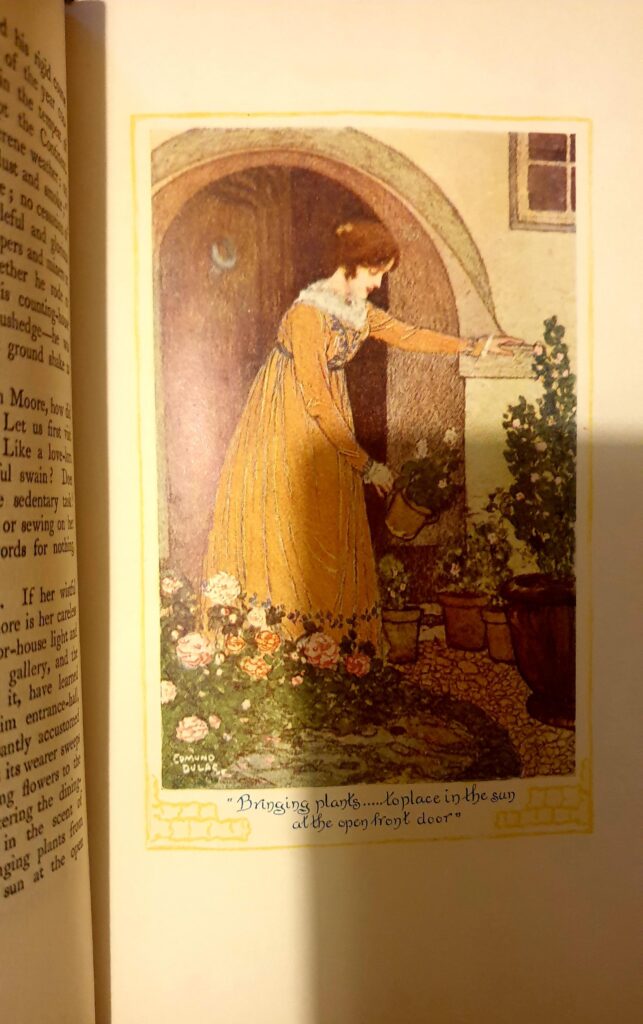

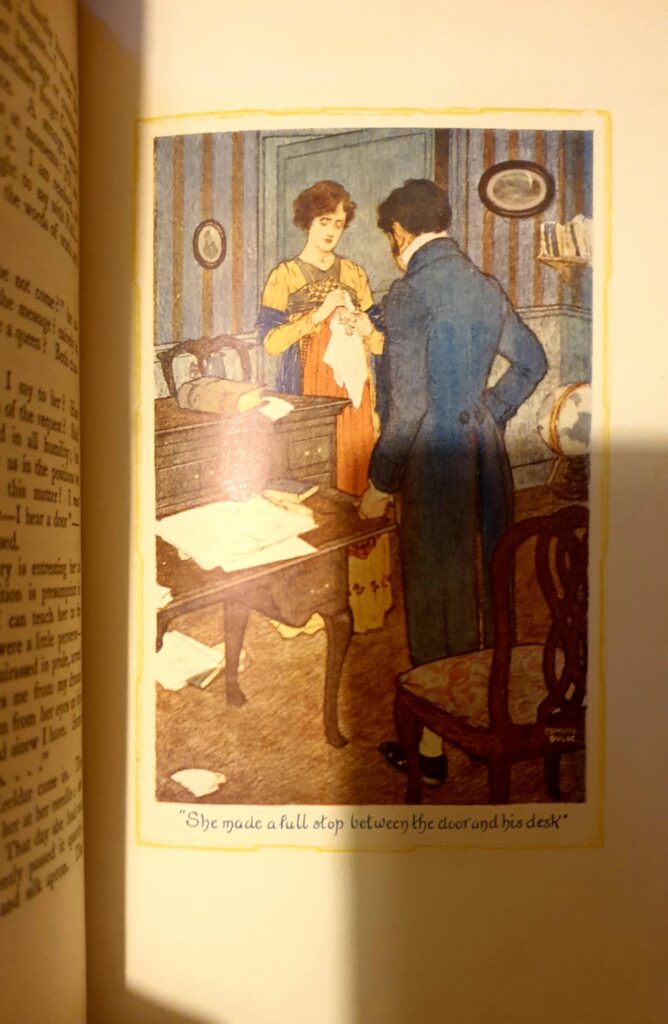

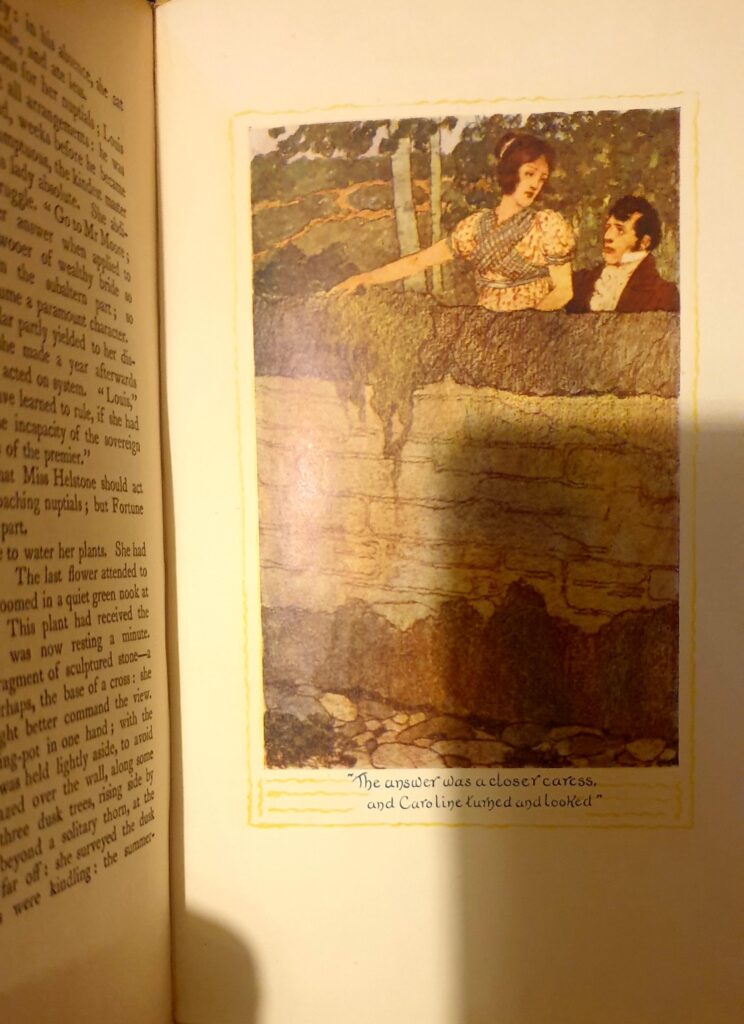

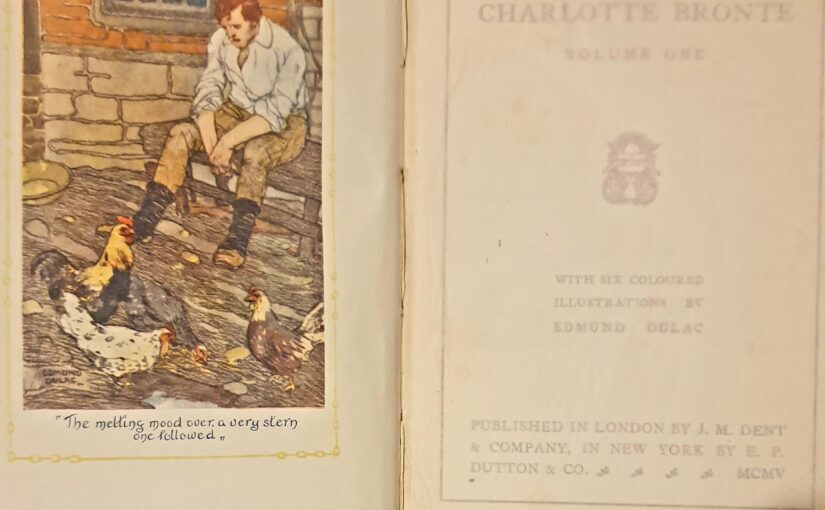

Incidentally, throughout this post I have used illustrations from the 1905 Dent edition of Shirley – one of the series of Brontë novels containing illustrations by Edmund Dulac. I’m lucky enough to have a complete set of these beautiful books, and they’re part of my Brontë collection which I will be selling/auctioning soon – look out for more details in next week’s post – I hope you can join me for it next Sunday.

Thank you for highlighting ‘Shirley’. You do not mention the background to the novel in Spen Valley, West Yorkshire and the links to the Luddites and the textile trade. Perhaps you could do another post on this. Her friendship with Mary Taylor of Red House, former museum, which is soon to be sold off by Kirklees Council is of interest. Also the missing silent film of 1922 of the novel.