Today in the United Kingdom has seen a suitably solemn recollection of Remembrance Sunday. It’s a day when we remember wars of the past, when we remember the soldiers who fought in them and the civilians caught up in them, and think of wars still being waged across the globe. Human civilisation has changed a lot in the last two thousand years, at least on a technological scale, but one thing has remained constant: war. Group has fought group and country fought country in every century since then, and surely this is a pattern which will continue until the end of time.

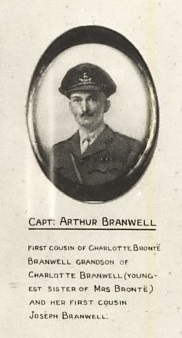

Certainly war was present in the time of the Brontës, as we shall see, but it was a relative in the succeeding generation who was to see the horrors and the twisted triumphs of war up close and personal. It may seem astonishing that a Brontë relative was amidst the hellish spectacle of the first world war, but that’s exactly what Captain Arthur Branwell was. He was in fact just one generation away from Anne Brontë and her siblings, in other words he was a first cousin once removed. His father Thomas Brontë Branwell was the son of Charlotte Branwell (who had kept her surname by marrying her cousin Joseph Branwell). Thomas was given his middle name in tribute to his mother’s elder sister who had married and taken the Brontë name. This sister was, of course, Maria Branwell who married Patrick Brontë in Yorkshire on exactly the same 1812 day as Charlotte married Joseph in Cornwall – a remarkable triple wedding separated by 400 miles.

Marrying cousins was nothing new for the extended Branwell family of Penzance, for Thomas Brontë Branwell travelled 400 miles from Cornwall to Haworth in 1851. His purpose was to propose to Charlotte Brontë! After being turned down by Charlotte, something she also did to Ellen Nussey’s brother Henry, Thomas married a woman named Sarah Jones. Their son kept up the family tradition of marrying a cousin –a cousin rather remarkably named Charlotte Brontë Jones! So whilst the father failed to marry a Charlotte Brontë the son succeeded in doing so, and it was this very son, the husband of Charlotte Brontë Jones, who found himself amidst the unspeakable horrors of France in World War One.

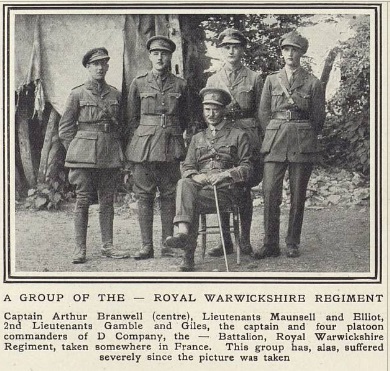

Born in 1862, Arthur was a military man by profession. He had served with distinction in the Boer War in South Aftrica and had actually retired from service by the time war in Europe was declared in 1914. Like many others, however, Arthur Branwell was called out of retirement and at first took up a role as an officer in charge of training new recruits. Before long he was somehow in France itself, where he was captured forever in this photograph of the officers of a group of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. The photograph shows Captain Branwell with his supporting officers, two First Lieutenants and two Second Lieutenants.

As the caption notes: ‘This group has, alas, suffered severely since the picture was taken. In fact, Lieutenant Maunsell was killed in France, 2nd Lieutenant Gamble was killed in Palestine, Lieutenant Elliott and 2nd Lieutenant Gamble were killed at the Battle of the Somme. Only the seated figure, our Captain Branwell, survived the war and returned to England.

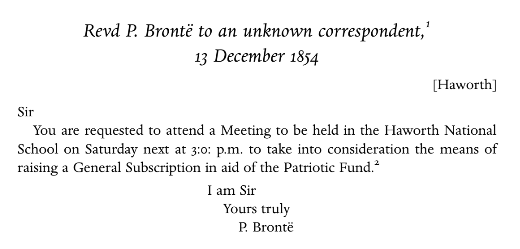

What do we know of the Brontë sisters’ attitudes towards war? The childhood Brontë tales of Angria and Gondal were full of intrigue, battles and conflict. They were fierce patriots, and we know that in 1854, the year of her marriage, Charlotte Brontë was helping her father Patrick raising money for the newly launched Patriotic Fund. This was a fund set up by the government to raise money for the widows and orphans of military personnel lost during the Crimean War, raging at the time. A letter sent by Patrick Brontë to an unknown parishioner at the time is reproduced below.

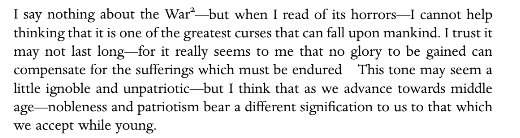

It should be noted that whilst the letter is seemingly sent by Reverend Brontë, it was actually in the handwriting of his daughter Charlotte. The Crimean war was at the forefront of Charlotte’s mind at this time, as we see in this letter of 6th December 1854 to Margaret Wooler. In this letter Charlotte Brontë gives a frank appraisal of the futility of war; Charlotte’s patriotism and love of her country is undiminished, but now she sees war as ‘one of the greatest curses that can fall upon mankind.’

For all those afflicted by that curse, yesterday, today and tomorrow we shall remember them. I hope you can join me next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.