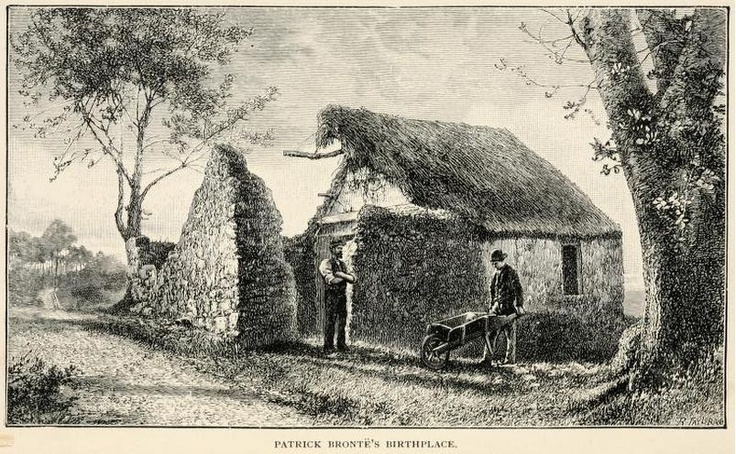

St. Patrick’s Day is just a few hours away; it’s a great day to celebrate all things Irish, wherever in the world we are, but in the Brontë household within Haworth Parsonage it was a day for a more personal celebration – for in Drumballyroney, County Down, on 17th March 1777 a boy was born who would begin the story of the most famous literary family of them all: Patrick Brontë.

In today’s we’re going to wish an early birthday to Patrick Brontë by looking at some reports of first person encounters with those who met him, published in newspapers and periodicals at the time he still lived:

Bradford Observer, 19th November 1857, ‘A Day At Haworth’, J.W.F.

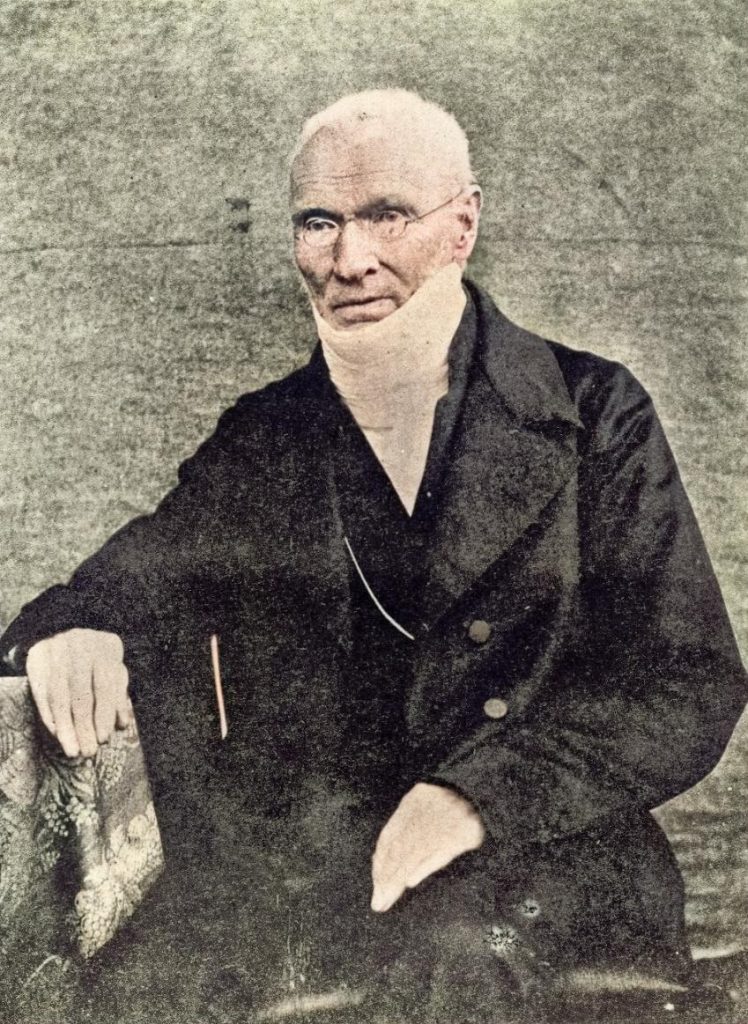

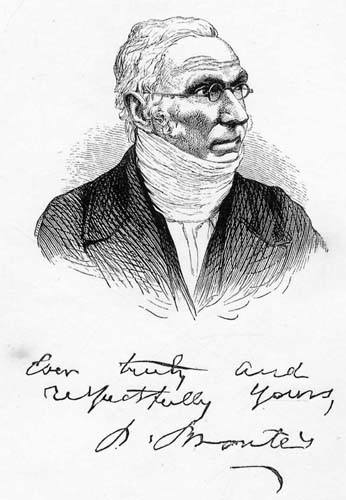

It was on a beautiful morning in August that my friend Puzzlecraft and myself set off to visit Haworth… Haworth is five miles from Keighley, the road is uphill most of the way and decidedly uninteresting, as your view is confined to the turnpike, the walls on either side acting as blinders. For two miles, however, before you enter the village you have it in full view, and the thoughts which it suggests are quite sufficient to employ your mind until you reach the bottom of the eminence whereon it stands. Haworth is most peculiarly situated. It is built in a circumspect fashion, up a steep hill, with a brook at the base, the church and parsonage at the top, and beyond that illimitable heather. It is a genuine Yorkshire village, macademized after a fashion, with no particular distinction drawn between the footpath and the road. The houses are of all sizes and shapes, like a wilderness of monkeys; some low-browed and flat-topped, poking themselves prominently forward, like a dowager at a dinner party; others small and spare, crushed out of all form into a corner, like a little man in a crowd or an unprotected female. Queer, quaint and quiet is the old village, reposing lazily against the hill side – yet not unvisited by the progressive principles of the age; for we found two or three shops at the west end garnished with plate-glass windows, and we even discovered the preliminary paraphernalia of a gas company. As we walked slowly up the street, we lighted upon a chemist’s shop, with a frame of photographic portraits hung outside. In the centre was the likeness of an elderly gentleman, with white hair, strongly marked but expressive features, and a peculiarly large neckcloth. “Mr Brontë!” we both exclaimed in a breath, although we had neither of us ever seen the gentleman or his portrait. There was such a striking individuality upon the countenance, that we recognised at once the original so plainly painted by Mrs Gaskell. We put up at the ‘White Lion’ and ordered dinner. Mine host, whose outer man, attired in a cap and a white shooting jacket, was eminently suggestive of terrier-dogs, went off forthwith to the parsonage to summon his maid servant, who had gone to wait upon the rector during the temporary absence of the regular domestic. Presently she came down, and in an unsophisticated Yorkshire fashion, as if anything she had to say was not of the slightest importance, she gave us her few particulars respecting the Brontë family. “Her family had lived at the parsonage for long – she had often been there herself – had seen Mrs Nicholls writing a great deal; it was when she was writing ‘Jane Eyre’ – had oft carried large parcels to the post and wondered what was in them – Mrs Nicholls was very small, Miss Emily was bigger a good deal – they were all great walkers, used to go up on to the moor for hours together – had seen Mrs Gaskell but didn’t know much about her – Mrs Nicholls had never got the better of a cold she caught going one winter’s day onto the moor to the waterfall, cascade Mrs Gaskell called it.” We asked her if she thought Mr Brontë would be annoyed if we called upon him:- “She didn’t know – there had been lots of people there, but he didn’t often see any of them.” We requested of her to take our cards up to the parsonage, and to say that if Mr Brontë was disengaged there were two gentlemen who would be happy to wait upon him; and, while she delivered the message, we went up to view the house and churchyard, round which cluster now so many mournful and hallowed associations…

Returning to our inn, we received Mr Brontë’s invitation to visit him, with which we immediately complied. We were ushered into a small front parlour, and very cordially saluted by the original of the photograph we had seen in the chemist’s shop. Truly a most noticeable man is Mr Brontë, and worthy to be the father of such a family. Though now well up in years (he told us his age, but it has escaped our memory), he appears quite hale and fresh, and preaches regularly every Sunday morning. He has a grand face, indicative of a power and energy which are merely mellowed by time, and shaded somewhat mournfully by suffering. One glance at that physiognomy assures you that its possessor has been shaped by nature after a model of his own – a man of strong passions, but stronger self-control; of warm emotions, but adamantine will – a man possibly eccentric, but whose eccentricities merely prove the positive tendency of his being, and the strength and struggles of his soul. This we must say, that we never saw a finer physique, more courteous and gentlemanly bearing, and more sincere and correct feeling than we met in Mr Brontë. Mournful was it to see the venerable man, and to know that of all his children – the gifted, the admired, the affectionate – not one was left. And most mournful was the thought that in this house – in this very room where we now are – those three sisters wrote their books and read their manuscripts to one another; the chair we sat upon they had handled; they have perused those volumes; watched the stars and snow-storms from those windows; their very presence seems still to linger here; and though they rest in yonder gray church, cold and still, we feel their spirits solemnizing and subduing us, and bidding us, beneath the shadow of the dead but deathless daughters, forbear to trench upon the feelings of the father, or to speak, save reverently and low.

After sitting about a quarter of an hour with Mr Brontë, we took a five minutes run on to the moor; then, with one last glance at the vicarage, the church, the graveyard, and the school, we turned homeward. We purchased a couple of photographic portraits of Mr Brontë as we passed the chemist’s; and we were just leaving the village when we encountered a comical fellow, with a merry mouth and an eye like a weazel’s. He had been a boon companion of poor Branwell, and many strange and characteristic stories did he tell us of their exploits in former days, the which, however, we shall not here record. Let those who have passed away repose in peace:- delicacy forbids the blazoning abroad of the failings of the dead, especially when those still live upon whose feelings the repetition of such tales must strangely jar.

The Scotsman, 18th September 1858, ‘A Visit To Haworth – The Brontë Family’, T. H.

Near Haworth I got many little traits of the family, all indicating the kindly and respectful feelings with which its various members are still regarded in the district. One young man belonging to Haworth, whom I overtook, a worker now at one of the Keighley factories, informed me that when a boy he frequently had occasion to be in the parsonage, and was often regaled with a tune on the piano, a pocketful of fruit, etc. Charlotte seemed generally to be considered the most affable, having a smile and a kind word for everybody; Emily and Anne were more reserved, and for that reason not quite so great favourites. Mr Brontë was spoken of by everyone in terms of the highest respect, even by those whom on many occasions he had opposed on ecclesiastical matters, dissent being strong in the vicinity. I had neither the intention nor expectation of seeing him; but the sexton, who acts as guide to the church, etc., having told me that Mr Brontë, when well, was always glad to see strangers, I was vain enough to send up my card, and had the pleasure of a little conversation with the venerable patriarch, now more than eighty years of age, and the sole survivor of his family. He was very kind, and spoke of Scotland, and Burns, more particularly, cordially, and with discrimination. Although frail he enjoys tolerable health, and in general preaches once every Sunday; Mr Nicholls, Charlotte’s husband (who is still curate, and whom I saw about the village), doing the principal part of the duty.

Fraser’s Magazine, October 1859, ‘About The West Riding’, Devonia

The attendance was small in the morning, but better in the afternoon, when Mr Brontë preached; owing to his advanced years, he is not able to attend the whole of the service, but comes into church when the afternoon prayers are half over. A most affecting sight, in truth, it is to see him walking down the aisle with feeble steps, and entering his solitary pew, once filled with wife and children, now utterly desolate, while close beside it rises the tombstone inscribed with their names. Full of sorrow and trouble though his life has been, the energy of the last survivor of the race seems not a whit abated; his voice is still loud and clear, his words full of fire, his manner of earnestness. Lucid, nervous, and logical, the style of his preaching belongs to a bye-gone day, when sermons were made more of a study than they are now, and when it was considered quite as necessary to think much and deeply, as to give expression to those thoughts in language not only impressive and eloquent, but vigorous and concise. It would not be easy to give a faithful impression of the impression which Mr Brontë evidently produces upon his hearers, or of his own venerable and striking appearance in the pulpit. He used no notes whatever, and preached for half an hour without ever being at a loss for a word, or betraying the smallest sign of any decay of his intellectual faculties. Very handsome he must have been in his younger days, for traces of beauty most refined and noble in expression, even yet show themselves in his features and in his striking profile. His brow is still unwrinkled; his hair and whiskers snowy white: lines very decided in their character are impressed about the mouth; the eyes are large and penetrating. In manner he is, as may have been gathered from what has been already said, quiet and dignified.

Bradford Observer, 27th June 1861, William Dearden

It is a duty I owe to the memory of my late venerable friend, and in fulfilment of a sacred promise, to place his character in a true light before the world; and this is the more imperatively necessary, because – though Mrs Gaskell has, in her later editions of Charlotte Brontë’s life, toned down some of its harsher features in obedience to conviction of their distortion and untruthfulness – it still stands prominently forth in repulsive stoical sternness and misanthropical gloom. My acquaintance with Mr Brontë extends over a long series of years. In the early portion of that acquaintanceship, I had frequent opportunities of seeing him surrounded by his young family at the fireside of his solitary abode, in his wanderings on the hills, and in his visits to Keighley friends. On these occasions, he invariably displayed the greatest kindness and affability, and a most anxious desire to promote the happiness and improvement of his children. This testimony, it is presumed, will have some weight, especially with whose who wish to form a correct estimate of human character.

It will be remembered that Mr Brontë’s children were deprived of their mother when they were at a very tender age. We are led to infer from Mrs Gaskell’s narrative, that their father – if he felt – at least did not manifest much anxiety about their physical and mental welfare; and we are told that the eldest of the motherless group, then at home, by a sort of premature inspiration, under the feeble wing of a maiden aunt, undertook their almost entire supervision. Branwell – with whom I was on terms of literary intimacy long before his fatal lapse – told me, when accidentally alluding to this painful period of in the history of his family, that his father watched over his little bereaved flock with truly paternal solicitude and affection – that he was their constant guardian and instructor – and that he took a lively interest in all their innocent amusements. Such – before the blight of disgrace fell upon him – is the testimony of Branwell to the domestic conduct of his father. “Alas!” said he to me, many years after that sad event, “had I been what my father earnestly wished and strove to make me, I should not have been the wreck you see me now!” Poor Branwell! May his sad example prove a warning to others to shun the gulf of misery into which he was prematurely plunged! If Mr Brontë had been the cold indifferent stoic he has been represented, the perpetual outflow of love and tenderness in regard to him from the hearts of his children, could not have been naturally expected. An unfeeling father ought not to complain, if he reaps but a scanty harvest of filial duty and affection in return for what he has sown. Love begets love – a saying not the less true, because it is trite.

As Mr Brontë’s children grew up, he afforded them every opportunity his limited means would allow of gratifying their tastes either in literature or the fine arts; and many times do I remember meeting him, little Charlotte, and Branwell, in the studio of the late John Bradley, at Keighley, where they hung with close-gazing inspection and silent admiration over some fresh production of the artist’s genius. Branwell was a pupil of Bradley’s, and, though some of his drawings were creditable and displayed good taste, he would never, I think, on account of his defective vision, have become a first-rate artist. In some departments of literature, and especially in poetry of a highly imaginative kind, he would have excelled…

The cold stoicism attributed to Mr Brontë was apparent only to those who knew him least; beneath this “seeming cloud” beat a heart of the deepest emotions, the effects of whose outflowings, like the waters of a placid hidden brook, were more perceptible in the verdure that marked their course than in the voice they uttered. God, and the objects to whom that good heart swelled forth in loving kindness – and the latter only, perhaps, very imperfectly – know the depth and intensity of its emotions. He was not a prater of good words, but a doer of them, for God’s inspection, not man’s approbation. Every honest appeal to his sympathy met a ready response. The needy never went empty away from his presence, nor the broken in spirit without consolation.

Dearden was a close friend of Patrick Brontë’s, but the other correspondents only met him on fleeting visits to Haworth but together they give a compelling vision of a remarkable man. Patrick Brontë was curate at Haworth for over 40 years, but his impact on literature, thanks to his daughters Charlotte, Emily and Anne, is even more enduring.

Happy (nearly) 248th birthday Patrick Brontë, happy St. Patrick’s Day eve to you all, and I hope you can join me next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.