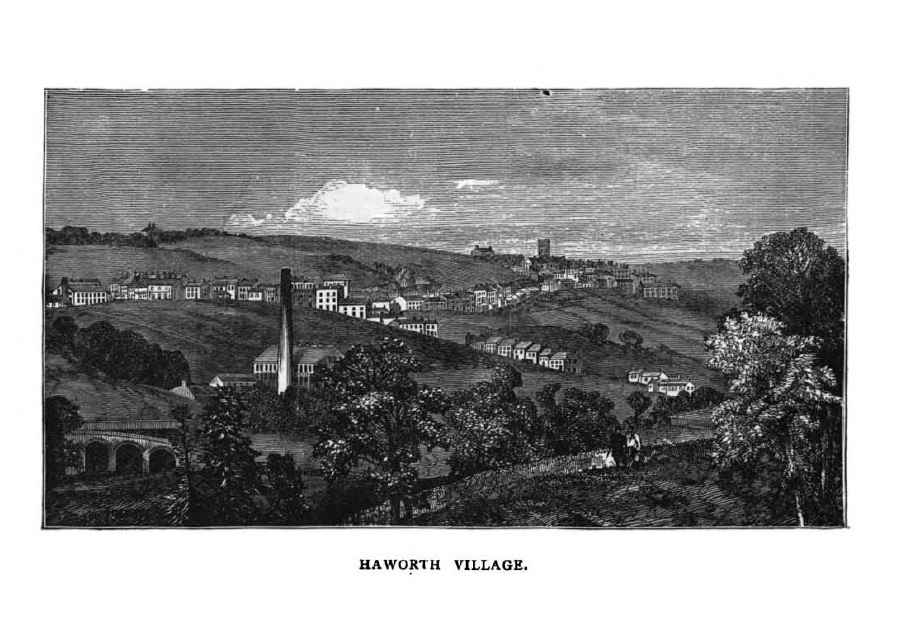

Easter approaches, a time which must have been busy, reflective and eventually joyous in the Brontë household at Haworth Parsonage. The village of Haworth has become synonymous with the Brontë sisters, drawing tourists from across the globe. Wherever you go in the village you will see the Brontë name, and long may that continue. Tourists want to visit the Parsonage, now a magnificent museum, of course, they want to visit inns like the Black Bull and conjure up images of Branwell Brontë sat on his three legged chair, and they also want to see the moors which stretch away from the village with bleak magnificence. The moors are a timeless reminder of the landscape the Brontës knew, they seem almost unchanged, but they are under threat.

In Emily Brontë’s breathtaking novel the moors seem to be as much of a character as Heathcliff or Catherine. It’s little wonder, for whilst the painfully shy Emily hated mixing with people (or at least people she didn’t know) she liked nothing more than walking on the moors. It is said she would walk up to twenty miles a day across the Pennine moors towards and then into Lancashire, an astonishing feat given the footwear she and others wore at that time. There was certainly no resemblance between the shoes of 1840 and the hiking boots of today, but Emily and others like her simply walked more in those days long before any form of transport other than four legged horse power.

Charlotte Brontë gave us fascinating glimpses of the moors, and the impact they had on the Brontë family, in her writing. In a letter of 22nd May 1850, addressed to W. S. Williams, Charlotte writes mournfully of her attempts to come to terms with the deaths of her sisters Emily and Anne:

“I am free to walk on the moors – but when I go out there alone everything reminds me of the time when others were with me and then the moors seem a wilderness, featureless, solitary, saddening. My sister Emily had a particular love for them, and there is not a knoll of heather, not a branch of fern, not a young bilberry leaf not a fluttering lark or linnet but reminds me of her. The distant prospects were Anne’s delight, and when I look round, she is in the blue tints, the pale mists, the waves and shadows of the horizon. In the hill-country silence their poetry comes by lines and stanzas into my mind: once I loved it – now I dare not read it – and am driven often to wish I could taste one draught of oblivion and forget much that, while mind remains, I never shall forget.”

In the same year Charlotte wrote a preface for a new edition of Emily’s Wuthering Heights and she returned to those thoughts, saying of the novel.

“It is rustic all through, It is moorish, and wild, and knotty as the root of heath. Nor was it natural that it should be otherwise; the author being herself a native and nursling of the moors… Ellis Bell did not describe as one whose eye and taste alone found pleasure in the prospect; her native hills were far more to her than a spectacle; they were what she lived in, and by, as much as the wild birds, their tenants, or as the heather, their produce. Her descriptions, then, of natural scenery, are what they should be and all they should be.”

For now, people can and do walk those same moors and hills, take in the same views and prospects, see the wild birds fly and the heather moving in a whispering wind. But the wind has become the moor’s enemy, or at least it is being harnessed by the moor’s enemy.

Plans are well underway for a huge new windfarm installation to be installed across the Calderdale moors. There are 65 proposed sites, and one of them is the Walshaw Moor area which is home to a plethora of previously protected wildlife, and home to Top Withens. It is the moorland walked by Emily Brontë, by Charlotte Brontë, by Anne Brontë. The moorland that people still walk today and look across to the glorious ruins of Top Withens, imagining Heathcliff stalking moodily by. Soon that some view will be filled with huge turbines and the relentless hum of nature being turned into commodity, of money being made at every turn of a white turbine sail.

Local poet, campaigner and Brontë enthusiast Lydia Macpherson is one of the people leading the campaign against the proposals, and she is sharing a petition aimed at protecting peat moors such as those around Haworth. You can sign the petition at this link, it only takes a moment:

https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/701290

On more positive news, another Brontë site of pilgrimage, the Brontë birthplace at Thornton, moves ever closer to its public opening, and it looks wonderful. It featured on the BBC’s ‘The One Show’ on Monday and if you missed it you can still catch the episode on the BBC iPlayer.

The beautiful image at the head of today’s post, by the way, was taken by talented photographer Dave Zdanowicz for use in my book In Search Of Anne Brontë. I hope, if you are marking the day or simply looking forward to eating a chocolate egg or two, you have a happy run up to Easter and I hope to see you here next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.