Anne Brontë, like her sister Emily, was a great lover of nature and animals, and this was reflected in all three of their novels. It became almost a shorthand for virtue in a character, the villains mistreated animals whilst the heroes and heroines were kind to them.

In Anne’s first novel, Agnes Grey, the governess first has to deal with the monstrous Bloomfield family, modelled on the Inghams of Blake Hall, Mirfield that she had worked for. The young Tom Bloomfield likes to torture birds, setting traps and then killing them in various horrible ways. In this he is encouraged by his father and uncle, who think that this is a proper and manly way for a boy to behave. Agnes takes a very different view, and when she finds that Tom has a nest of fledglings that he intends to torture, she drops a stone on them killing them instantly and thus sparing them further torment.

If this was modelled on real life, as much of Agnes Grey is, then we can imagine how awful it must have been to carry this act of mercy through. Anne herself hints that this really happened in her preface to the second edition of The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall, when she writes:

‘Agnes Grey was accused of extravagant over-colouring in those very parts that were carefully copied from the life, with a most scrupulous avoidance of all exaggeration.’

Similarly in The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall, we see the bullying, abusive, drink sodden husband Arthur Huntingdon taking his young son hunting and smearing blood on his face.

Emily Brontë, often in company with Anne, would frequently take long walks across the moors near Haworth, rescuing injured animals that she found, bringing them home and nursing them back to health. In her great novel, Wuthering Heights, she uses this same shorthand to reveal how villainous Heathcliff really is. Nelly Dean, the books co-narrator, finds the first evidence that Heathcliff has eloped with young Isabella Linton in the shape of her dogs that he has left hanging. This was his wedding gift to his new wife, and a fitting symbol of the cruelty that was to come.

On the other side of this coin, Anne uses kindness to animals to demonstrate that a character is a hero. This is apparent in the character of Edmund Weston in Agnes Grey. We see him rescuing the old woman Nancy’s cat, before it is shot. He also rescues Snap, the dog that Agnes had loved and had to leave behind when she left the employ of the Murray family, modelled on the Robinsons of Thorp Green Hall.

Snap had been sent to a rat catcher much to the horror of Agnes, but later when she is walking along Scarborough beach she is delighted to see the dog run up to her:

‘I heard a snuffling sound behind me, and then a dog came frisking and wriggling at my feet. It was my own Snap – the little, dark, wire-haired terrier! When I spoke his name, he leapt up in my face and yelled for joy. Almost as much delighted as himself, I caught the little creature in my arms, and kissed him repeatedly. But how came he to be there?’

It is then that Agnes looks around and sees Weston, the man that she had loved and had to leave behind. He has bought Snap from the rat catcher and been ever on the look out for Agnes herself. Thus starts what is a very understated, and yet very romantic, end to the novel. It is very moving as well, when we consider that Weston is undoubtedly based upon William Weightman who had been snatched from Anne by cholera five years previously.

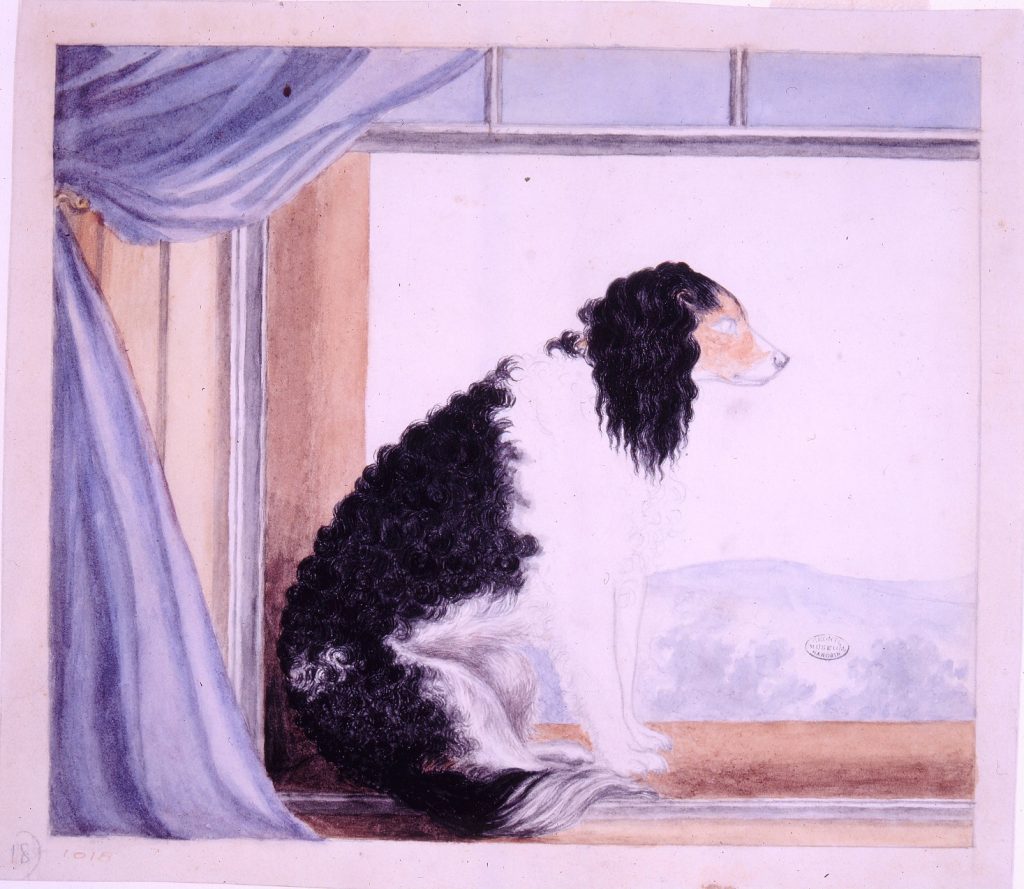

To Anne, and Emily, a love of animals was a prerequisite for a good character, and as a lover of animals myself I certainly concur with that. This love extended beyond the page and into their real lives as well, as they had a succession of pets, from geese, named Adelaide and Victoria after the royal princesses, to cats, rabbits, pheasants, hawks and canaries, and of course their famous dogs Keeper and Flossy.