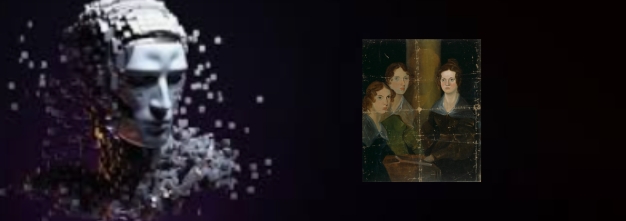

One thing that Britain can be incredibly proud of is its culture, its art and its literature. For a relatively small island we have created some of the world’s greatest and most enduring art, music and books. The Brontë sisters are one unique example of creative genius that this country can rightly be proud of. One reason, I feel, for their enduring success is that their novels and characters are oh so human and relatable – in the near two hundred years since their creation fashions, technology and the way we live and work have changed rapidly, yet these books are still as popular and as relevant today as they have ever been. Humanity, and human genius, is at the heart of the Brontës’ success, but is this brand of creativity coming under increasing threat from AI? That’s the question I’m posing in today’s special post, as I ask AI to generate new Brontë novel ideas.

ITV have been responsible for some of the greatest television of the past decades. Much loved comedies such as Rising Damp and George and Mildred, classic adaptations of Brideshead Revisited and Poirot, groundbreaking shows like The Prisoner, Upstairs Downstairs, Armchair Theatre, The South Bank Show and Cold Feet. All reached our screens thanks to ITV – and thanks to the humans who devised and wrote them. That could be about to change as the result of a job advertisement placed by ITV this week.

The ad was for an £80-95,000 job as ‘Head of Generative AI’. The successful candidate will “drive the strategy and execution of AI-driven transformation across ITV Studios and ITV’s streaming services,” and would be expected to use “implementation tools like AI-generated ideation, character development, and enhanced production graphics.”

In short, ITV is looking for someone to head up the creation and writing of TV shows made completely by AI. This is extremely problematic for more than one reason: not only can we expect the quality to drop considerably, there would also be a downgrading of human skills throughout the process and a loss of jobs involved in this creative process. Another, and increasingly controversial, process also rears its ugly head. Artificial Intelligence is a misnomer: there is no intelligence, as we could define it, being used by these computerised systems; in stark contrast, it actually trawls through material available on the internet at a vast pace and mashes it up into a finished piece that it hopes, through its algorithms and rules, will make some sort of sense. This means that AI writing and AI art is actually taking and utilising material created by humans without their knowledge or permission, and with no recompense to them. It is cyber plagiarism.

This advert makes quite clear that ITV are at this very moment planning to create AI television shows, and be under no illusion that this will affect the world of literature too. AI splurged books are not a dystopian future – they are already available and selling on sites such as Amazon. In fact Amazon itself is now advertising its own Titan AI creation system. For a price it will provide image and text generation, but how good will the results be?

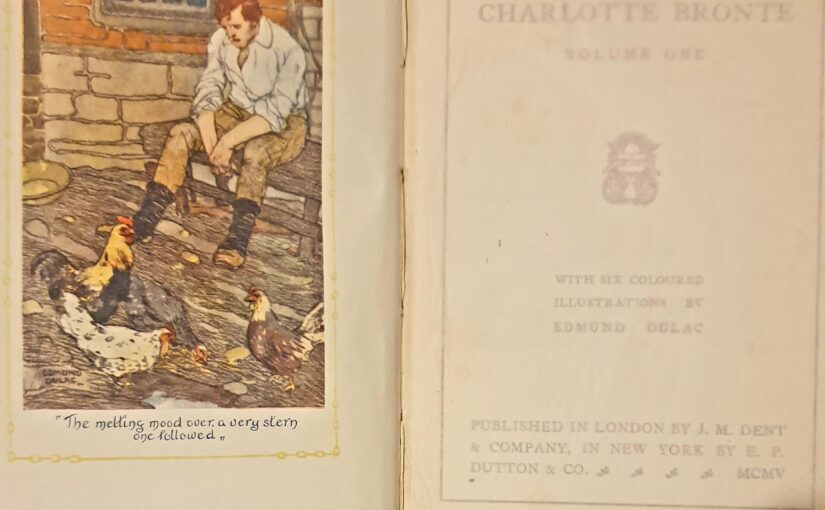

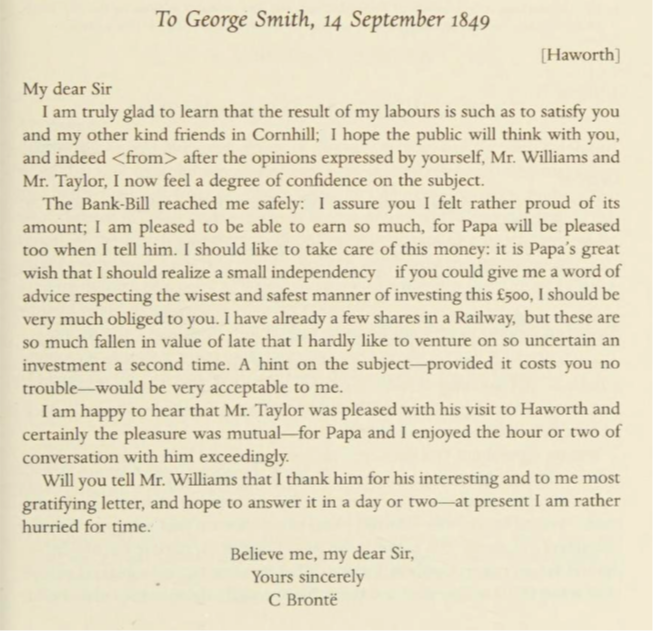

AI graphics are already ubiquitous, but it seems to struggle particularly with not only capturing the human spirit but human form – we see people with ears on their shoulders and extra fingers on their hands. How does AI text fare? I asked ChatGPT, the leading AI system, to give me the title and outlines for new novels by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. I then asked an AI image generator to create suitable covers. Here is what they came up with:

Charlotte Brontë: Title: The Shadows of Windcliff

Plot: “In a remote, windswept region of northern England, nestled on the edge of jagged cliffs overlooking a tempestuous sea, lies Windcliff Hall, a sprawling manor house as mysterious as the family that inhabits it. Margaret Elwood, a quiet but resilient young woman, is hired as a governess to care for the strange, reclusive daughter of Sir Arthur Windcliff, the brooding master of the estate.

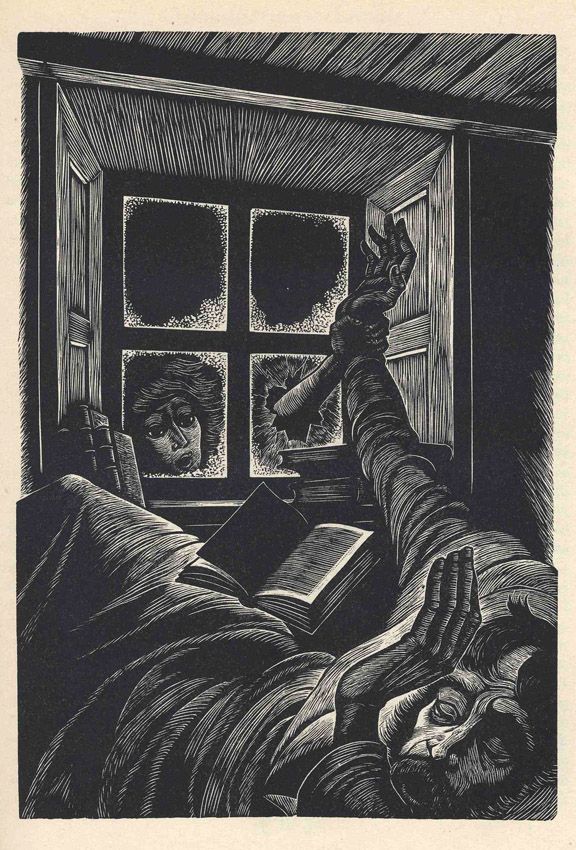

As Margaret settles into life at the forbidding manor, she is drawn into a world of secrets and suppressed emotions. The hall is filled with whispers of a family curse that haunts the Windcliffs – each generation marked by tragedy, madness, and mysterious disappearances. Sir Arthur, distant and brooding, carries a profound sorrow, and his daughter, Eliza, is unnervingly perceptive for her age, often speaking of shadows that move in the night and voices only she can hear.

Margaret is determined to uncover the truth of the curse and what happened to Sir Arthur’s late wife, whose death remains shrouded in ambiguity. As she digs deeper, she finds herself irresistibly drawn to Sir Arthur, despite the storm of emotions that roils between them. But the more Margaret uncovers, the more dangerous her situation becomes. The halls of Windcliff seem to pulse with an otherworldly presence, and Margaret must confront not only the mysteries of the past but also the shadows lurking within her own heart.

Gothic romance, eerie atmospheres, and Brontë’s signature exploration of internal struggle blend to create a tale of love, redemption, and the battle between light and darkness in the human soul.”

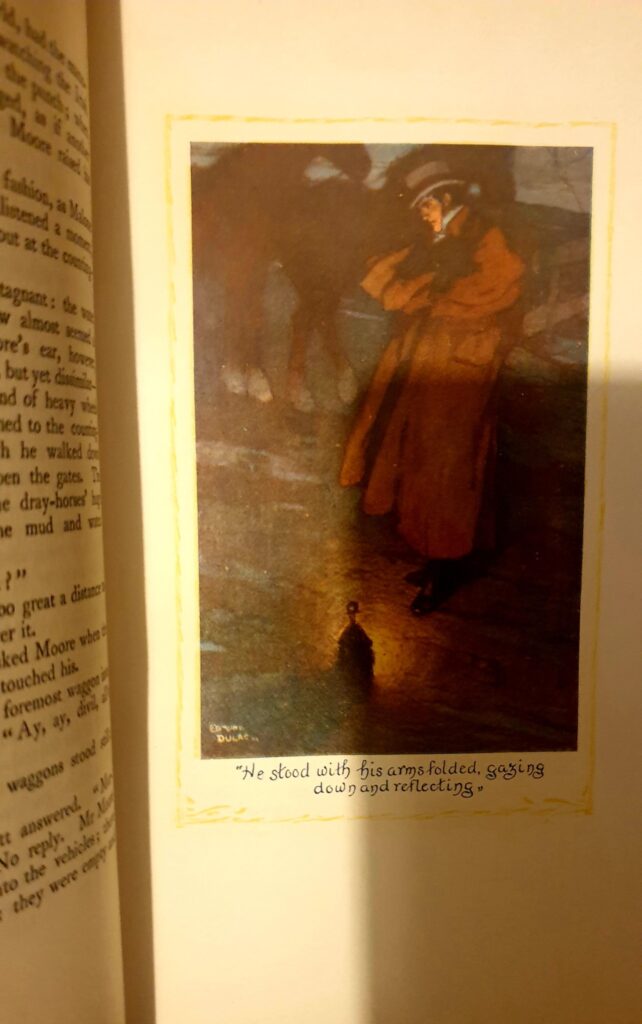

Emily Brontë: Title: Stormsong

Plot: “On the edge of the wild, untamed moors stands Darkswell Hall, an ancient mansion steeped in myth and mystery. The inhabitants of the nearby village whisper of curses, lost loves, and the restless spirits that haunt the windswept land. Into this world comes Lirael Morrow, a fiercely independent and headstrong young woman, who returns to her ancestral home at Darkswell after the sudden death of her father. Once a place of childhood wonder, Darkswell now feels suffocating, as though the very stones of the house are alive with unspeakable grief.

Lirael’s return sets in motion a chain of eerie events, beginning with the discovery of a strange, otherworldly song that seems to emanate from the heart of the moors on stormy nights. No one else can hear it but her, and its haunting melody draws her deeper into the desolate landscape, where she encounters a mysterious figure – a man who seems to belong as much to the moors as the sky and wind. This stranger, named Aidan Storme, is an enigmatic wanderer who speaks in riddles and appears only when the storms rage fiercest.

As Lirael becomes more entangled with Aidan, she learns of a long-buried feud between their families, one rooted in ancient betrayals and a love that defied both time and death. The curse that binds them is older than the moors themselves, a curse that stirs whenever the storm sings. Torn between her growing attraction to Aidan and the dangerous forces surrounding them, Lirael must unravel the mysteries of Darkswell Hall and her own family’s past before the storm’s song claims them both.

In the windswept desolation of the moors, Lirael is caught between the wild, untamable force of nature and her own tempestuous emotions. As passions run deep and hidden truths rise to the surface, she must decide whether to confront the dark legacy of her ancestors or be swept away by the storm.

Stormsong is an atmospheric tale of love, vengeance, and the powerful pull of destiny, filled with the gothic beauty, elemental fury, and deep emotional resonance that define Emily Brontë’s work. The novel explores the primal connection between the human soul and nature, the consuming force of desire, and the devastating power of secrets long kept hidden.”

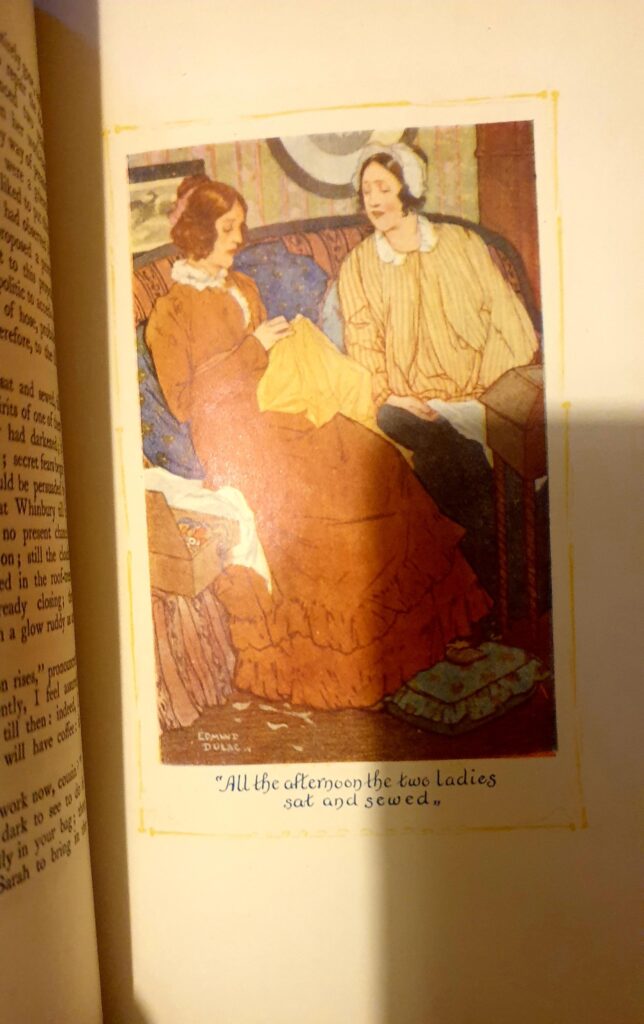

Anne Brontë: Title: Whispers of Wildfell Wood

Plot: In the quiet village of Windmoor, nestled at the edge of a dense, shadowy wood, lives “Clara Lyndon, a young governess who has spent her life caring for others, always putting duty before her own desires. After the untimely death of her father, she takes a position at Wildfell House, a crumbling mansion on the outskirts of the village, owned by the reclusive Mrs. Thorburn and her melancholic son, Edmund. The estate is surrounded by a thick, foreboding wood, which the locals believe is cursed, filled with whispers of past tragedies.

Clara, sensible and pragmatic, dismisses the superstitions, but she soon discovers that Wildfell House holds dark secrets of its own. Mrs. Thorburn is a shadow of a woman, haunted by the memory of her lost daughter, Eleanor, whose mysterious disappearance years ago is still spoken of in hushed tones. Edmund, brooding and deeply troubled, seems bound to the house and its secrets, battling unseen demons as he retreats further into himself.

As Clara becomes more entangled in the lives of the Thorburn family, she stumbles upon Eleanor’s old journals hidden in the house, chronicling a life of stifled dreams, forbidden love, and unbearable sorrow. The more Clara reads, the more she is drawn into the mystery of what truly happened to Eleanor – and why her name is whispered among the villagers with such dread.

Against her better judgment, Clara begins to grow close to Edmund, whose despair mirrors the emotions she’s kept buried within herself for so long. Together, they try to uncover the truth about Eleanor’s fate and the secrets that linger in the depths of Wildfell Wood. But the more they search, the more they realize that some truths might be better left buried.

In Whispers of Wildfell Wood, Anne Brontë crafts a story of quiet courage and inner strength, exploring themes of loss, isolation, and the power of speaking out against oppression. As Clara unearths the truth about the Thorburn family, she must also confront her own fears, finding the strength to carve out a path for herself in a world that has always told her to stay silent.”

I think we can all agree that whilst these plotlines have picked up some of the more obvious Brontë tropes, there is little to differentiate these efforts ‘by’ Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. It’s fair to say that they have failed to pick up on any of the subtlety of these incredible authors. Is that what we have to look forward to? I for one will prefer to read books, films and television shows written by actual humans.

I hope you can join me, as usual, on Sunday for another new Brontë blog post, and as always I promise it will be 100% written by a human – for better or worse.