Charlotte Brontë is associated with many places – Haworth obviously springs to mind, as does Thornton, the birthplace of the Brontës near Bradford, Scarborough where she travelled with Anne Brontë at the close of Anne’s life, and Brussels, where she went to school. In today’s post we look at another location Charlotte Brontë enjoyed, but one whose association with Charlotte is today little known: Hornsea.

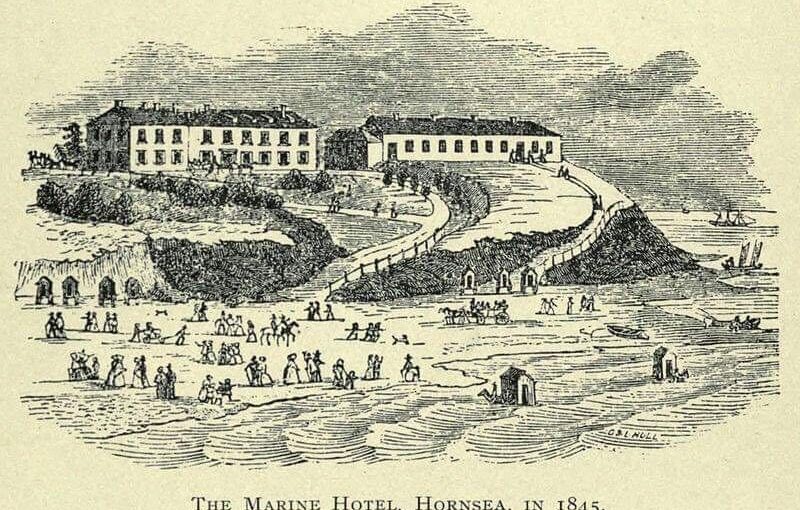

On this very day in 1853 Charlotte Brontë was making her way home after spending a week in Hornsea, the then fashionable resort in the East Riding of Yorskshire, 15 miles northeast of Hull. It expanded greatly after 1864 when the railway arrived in Hornsea, but at the time Charlotte visited a decade earlier it was still very popular among the middle and upper classes who came to seek out its healing waters.

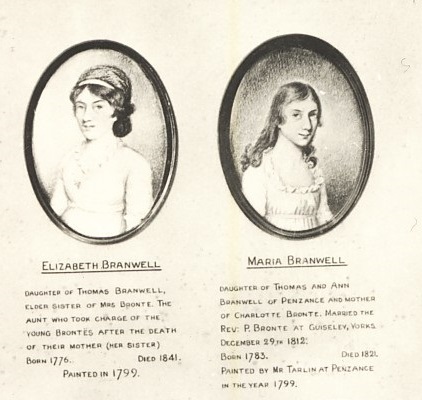

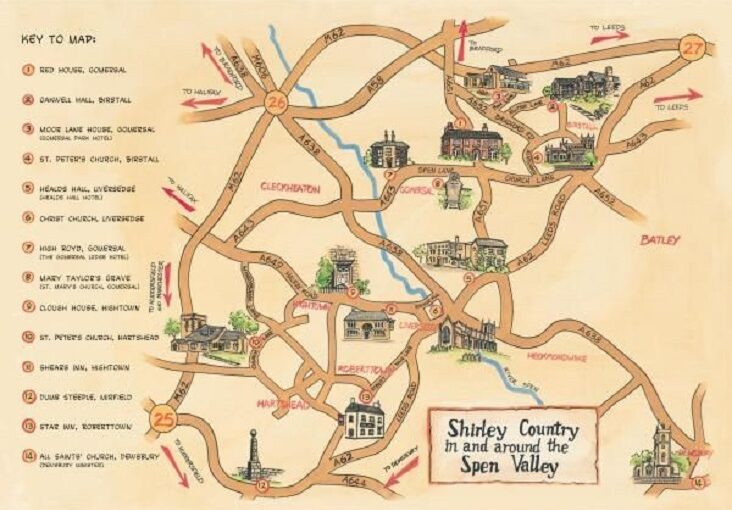

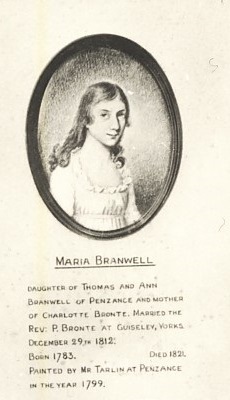

Like Bridlington and Scarborough further up along the east coast, Hornsea had a spa which attracted those who could afford to luxuriate and recuperate there. Charlotte Brontë, however, did not come to Hornsea for the spa but to see one of her oldest friends: Margaret Wooler. Miss Wooler, as Charlotte always respectfully called her, had been Charlotte Brontë’s teacher, then employer and then enduring friend. By 1848 as well as the home in Gomersal which Margaret shared with her sisters she also had a retirement home in Hornsea at which she spent her summers until cold weather sent her back to the West Riding again.

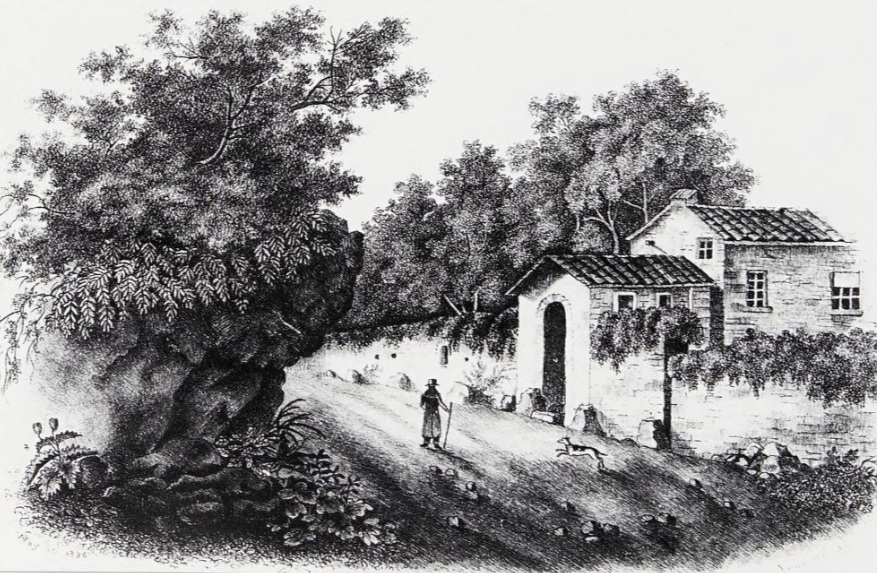

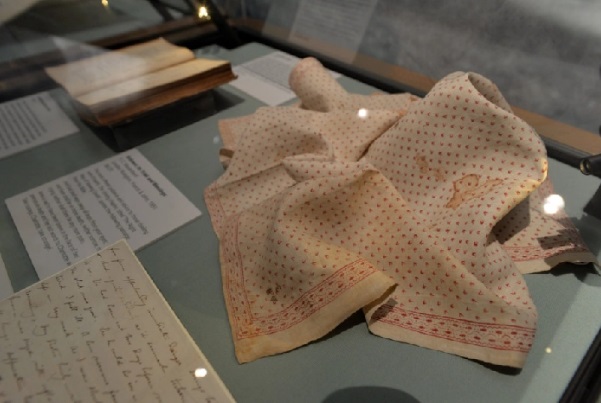

Margaret’s Hornsea abode was 4 Swiss Cottage, now known as 94 Newbegin. Thanks to the power of Google Maps above is a picture of that very building in modern times, hidden behind a vast hedge, and it was here that Charlotte Brontë stayed in October 1853. Hornsea Museum now lies opposite this house. At the time it was home to the Burns family, and in the local paper it advertised that “hot water sea-showers” were available in an adjoining cowshed.

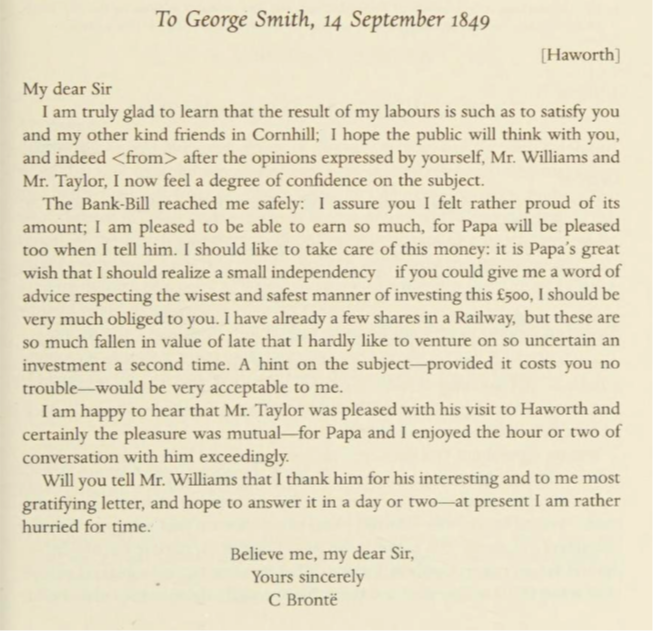

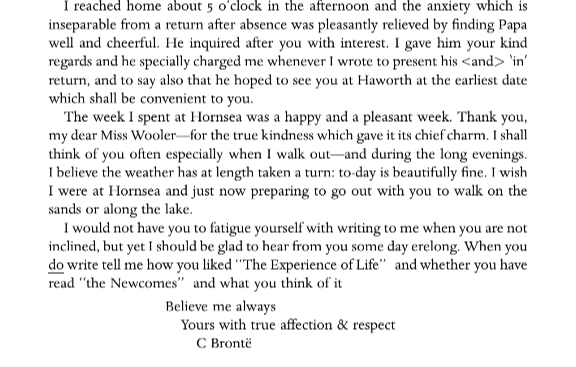

We know little of the day to day details of Charlotte’s visit, but it remained on Charlotte’s mind as two months later she wrote to Margaret:

“I did enjoy that week at Hornsea. I remember it with pleasure and I look forward to Spring as the period when you will fulfil your promise of coming to visit me. I fear you must be very solitary at Hornsea.”

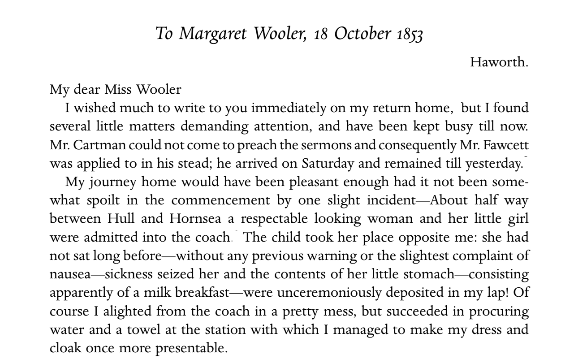

We also have an account that Charlotte gave after arriving back in Haworth from Hornsea – and it reveals rather an eventful journey home on a coach that would take her from Hornsea to Hull train station before a train back to Keighley and from thence on via gig or on foot to Haworth:

That brings a whole new meaning to ‘homesick’. If only Charlotte had had access to those sea-water showers after alighting from the coach! Charlotte didn’t get the chance to return to Hornsea; Margaret did indeed visit Charlotte Brontë in Haworth in the following year, but she did so to give Charlotte away at her wedding to Arthur Bell Nicholls. There is no plaque to Charlotte Brontë in Hornsea today, but until recently she was remembered in a way unique to this rather lovely little town. Hornsea was famous across Britain and beyond for its pottery. Alas, Hornsea Pottery stopped production in 2000, but not before they had brought out a range of crockery bearing the name ‘Brontë’. I have some pieces of Hornsea Brontë-ware myself.

I think this range would have looked very much at home in the Brontë kitchen. I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.