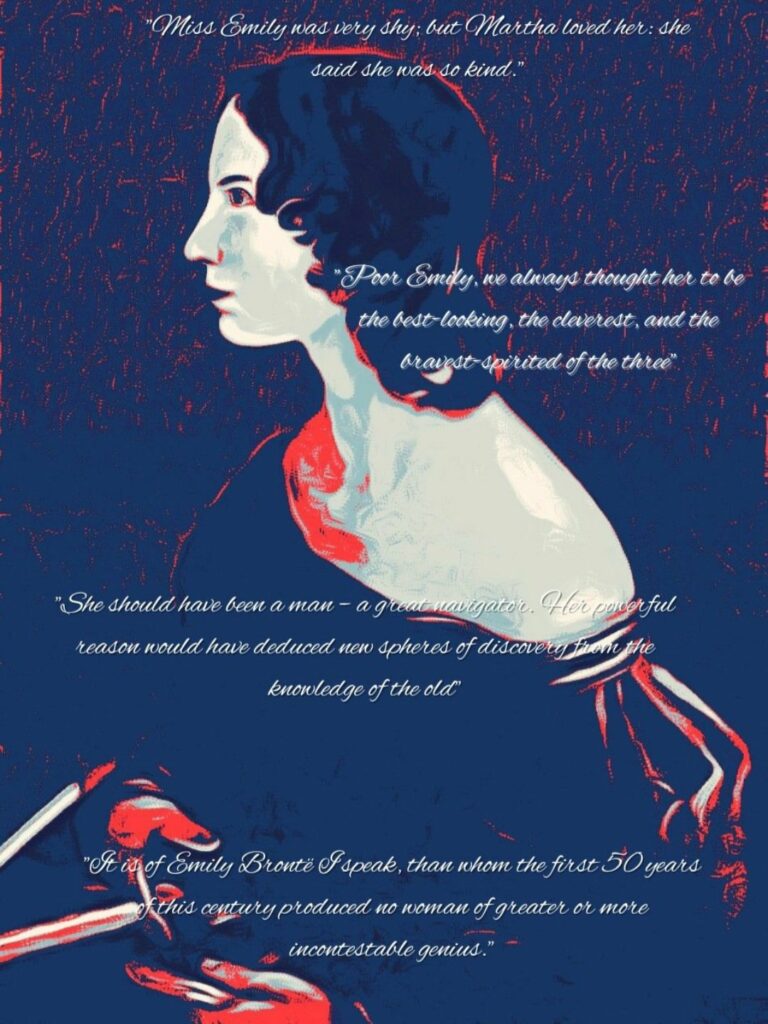

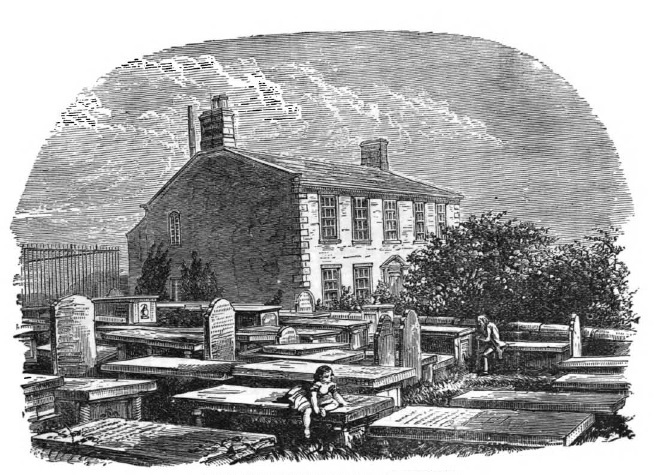

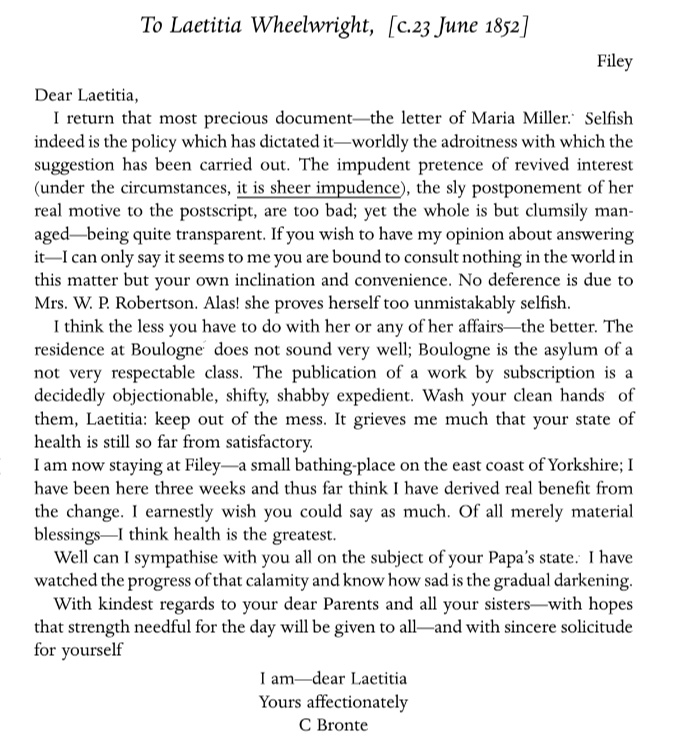

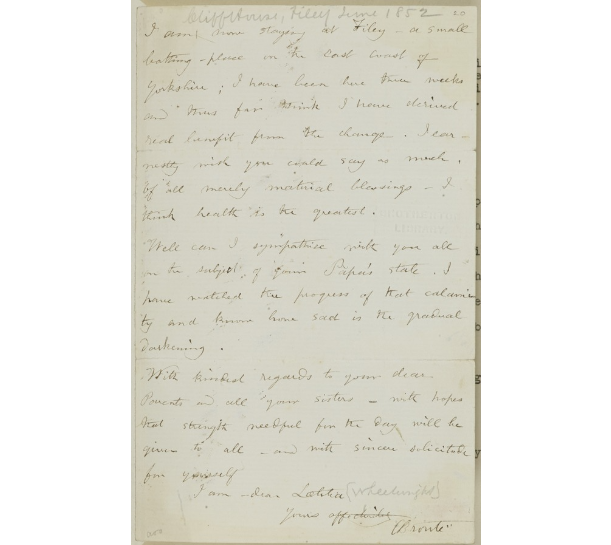

This week marked some important anniversaries in the Brontë story – the 30th July was the anniversary of the birth of Emily Brontë (and, exactly 140 years later) of Kate Bush who will always be linked to her thanks to a certain song. Today marks another date to remember, as it was on this day in 1928 that the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth first opened its doors to the public. That’s why I headed to Haworth this week, and why today’s post looks at the Brontë Parsonage Museum – past and present.

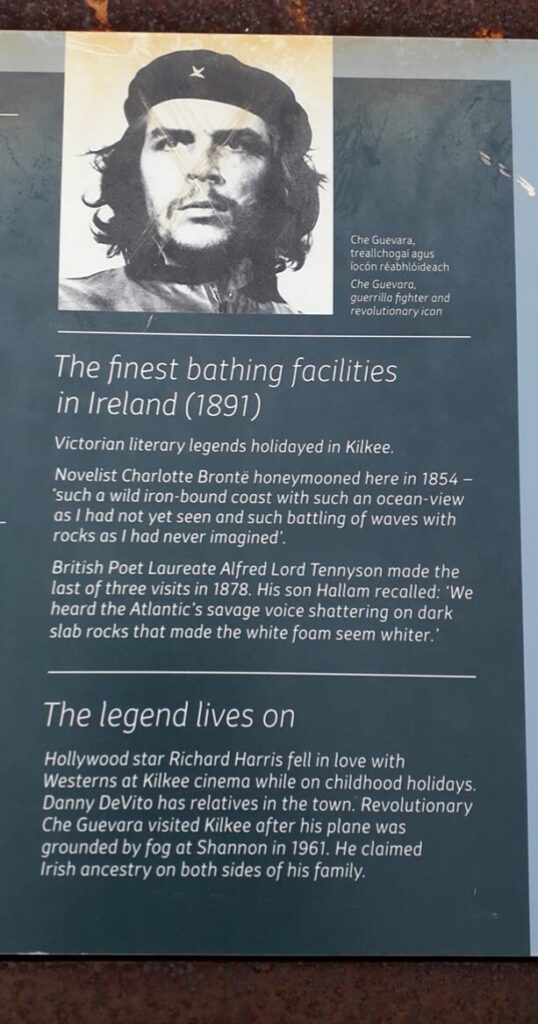

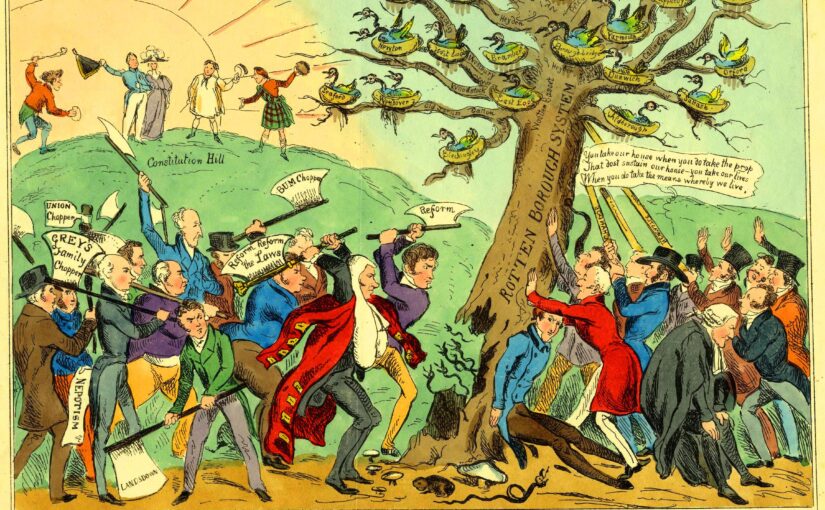

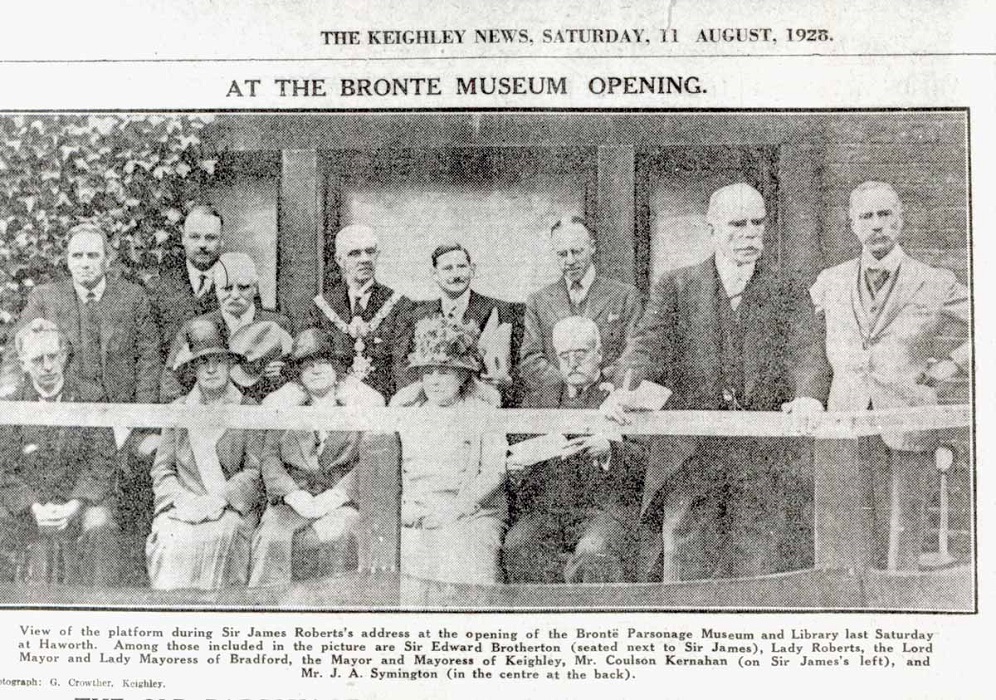

To start with, let’s fire up our time machines and head back to the 4th August 1928. If you were in Haworth on this day you would have been met with huge crowds stretching up Church Lane and down the cobbled Main Street – people were in their finery, so bowler and cloche hats were in abundance. What was drawing them there? The official opening of the Brontë Museum in what had, until then, been an active parsonage building belonging to the Church of England. This picture taken on that day captures the crowd perfectly:

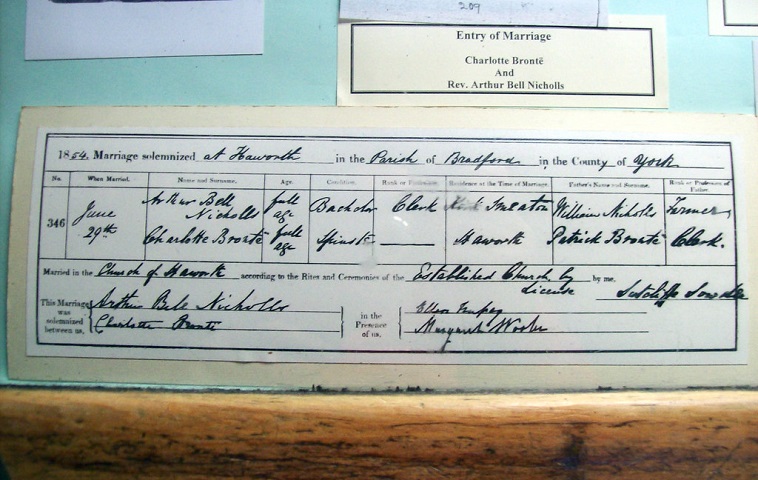

If we had been there that day we would have seen two of the great benefactors of the museum on the podium facing the large assembly of well-wishers: Sir James Roberts and Sir Edward Brotherton. Both are working class northerners who had become successful industrialists, and had used their wealth to share their love of the Brontës with the public. Sir James was born in Haworth, in the same week that Branwell Brontë died, and he still had vivid memories of Patrick Brontë, of Arthur Bell Nicholls and Martha Brown. It is Sir James who bought the parsonage building from the Church of England and immediately gifted it to the Brontë Society, allowing them to open it to the public. Sir Edward had built up a vast collection of Brontë memorabilia, alongside other literary gems, and he has gifted a large part of it to this new museum and to Leeds University – where it is now housed in the magnificent Brotherton Library.

Other notable people who thrilled the crowd were Mr and Mrs Branwell and Captain Arthur Branwell, the cousins once and twice removed of the Brontës and last surviving members of the Branwell family of Penzance who had provided the Brontë motherline. Another man presented to the crowd is Mr Holland, grandson of Charlotte Brontë’s friend and biographer Elizabeth Gaskell.

Perhaps the most moving and spontaneous aspect of the ceremony comes when Lady Roberts, wife of Sir James, was presented with a bouquet of white moorland heather by a local child. She stooped to kiss the child, and the whole audience applauded. The event was reported fulsomely by newspapers from as far away as Hastings in Kent, whose Observer newspaper gave this account:

‘The first time, we are told, never comes back, and the present writer will not soon forget his sensations on seeing for the first time, and so suddenly, the home of the Brontës. The experience was, at once, strange – and familiar. It was familiar because – in pictures, photographs, even on postcards, Haworth Parsonage is known to most of us. It was strange, because there is always something of strangeness on seeing for the first time a face, a scene, or an historic building, the pictured presentation of which is familiar to us. And, in the case of the Haworth Parsonage, the sense of strangeness was heightened by the fact that the old Brontë home struck one as more grimly grey-black, more bleakly-haggard, and more ghost-haunted, even than one had expected…

Before some of us had breakfasted, on the morning of August 4th, visitors all parts of the country, all parts of the Kingdom, all parts of the Empire – for one lady had come specially from Rhodesia, and one heard of folk who had journeyed from Canada, America, and the Antipodes – were pouring in by train, by car, by charabanc, motorcycle, push cycle, and not a few of the poorer classes, on foot. Haworth was, in fact, en fête, its streets fluttering with flags, and with Union Jacks floating from flagstaffs, or run out of windows of the more important buildings. At 2.45, Colonel Sir Edward Brotherton, who was to preside at the ceremony, arrived. Like Sir James and Lady Roberts, Sir Edward Brotherton has done great things for patriotic causes, raising at his own expense a battalion of the 15th West Yorkshire regiment during the War. His being in the chair was, thus, more than appropriate, for August 4th was an “historic” occasion, apart from the Brontë celebration.

The arrival of Sir Edward at 2.45 was followed at 2.55 by that of Sir James and Lady Roberts, who were received by Sir Edward, supported by the Lord Mayor of Bradford, and a very distinguished company. Within the gates of the Parsonage, and far without those gates, some thousands of persons were gathered. After Sir James had handed the title deeds of the Parsonage to Sir Edward, and the latter had eloquently, and gracefully made acknowledgement, little Catherine Butler Wood (daughter of the accomplished scholar and author, who is editor of the Brontë Society publications) presented Lady Roberts with a bouquet of white moorland heather. When Lady Roberts, in her gentle and gracious way, stooped to kiss the child (as did Sir James), this little “human touch” called forth enthusiastic hurras, and even cheers. The applause was no less enthusiastic when Sir Edward Brotherton claimed that the Brontë Society now had a museum which would bear comparison with those established in honour of Victor Hugo, Walter Scott and Robert Burns.

Next Sir Edward invited Lady Roberts to open the Parsonage, which she did with a golden key presented by the architect, Mr W. A. Ledgard, who, later, made a speech which, next to that of Sir Edward Brotherton and Sir James Roberts, was by far the most memorable oration from anyone present. Lord Haldane, who intended to be present at the ceremony, but was prevented by illness [a former Lord Chancellor, Haldane died suddenly two weeks later], sent a written and very striking tribute to the Brontës, which was read by Canon Egerton Leigh. Then came the vote of thanks to Sir James and Lady Roberts, which after it had been proposed, seconded, and supported, was enthusiastically and unanimously carried. Other speakers were Dr. J. B. Baillie and Dr. J. Hambley Rowe, both prominent members of the Brontë Society, but one regretted that so eminent an authority on the Brontës as Mr. Jonas Bradley, could not be persuaded to say a few words. The interest of the occasion was, however, not a little heightened by the announcement that Captain Arthur Branwell, and Mr. and Mrs. Branwell, relatives of the Brontë family, as well as Mr. Holland, grandson of Mrs. Gaskell, were present, and were invited by Sir James to ascend the platform, to say a few words…

Sir James said: “It is my first, and particularly pleasant, duty to place in the hands of Sir Edward Brotherton, the honoured president of the Brontë Society, the title deeds of the property of the Haworth Parsonage, which from today becomes, as the Brontë Parsonage Museum, the permanent home of the memorials of the Brontë family. My pleasure is enhanced by the fact that in performing this duty I am returning to the well-remembered scenes of my childhood and youth and to-day is an occasion when, standing on the verge of fourscore years, these early memories are vividly reproduced.

I was born in this parish in the same week in which the unhappy Branwell Brontë died: an event followed at intervals of distressing brevity by the deaths of Emily and Anne. Haworth has seen more than a few progressive changes since those far off times. Her people have moved into closer touch with a wider world life, and a good many of her children have achieved success in commercial and other pursuits. Were this occasion less important, and less impressive, I could revive many quaint recollections of Haworth folk, and Haworth ways, as I remember them in those mid-Victorian days – a people and manners now immortalised by the writings of those whose memories we are met to honour.

It is to me a somewhat melancholy reflection that I am one of the fast narrowing circle of Haworth veterans who remember the Parsonage family. I heard Mr. Brontë preach in the pathetic blindness of his old age. Mr. Nicholls frequently visited the schoolhouse we as children ate the mid-day meal in the interval of our elementary studies, while Martha Brown, the faithful servant to whom Mr. Brontë gave the money box, the contents of which she was “to keep ready for a time of need,” is still to me a well-remembered figure…

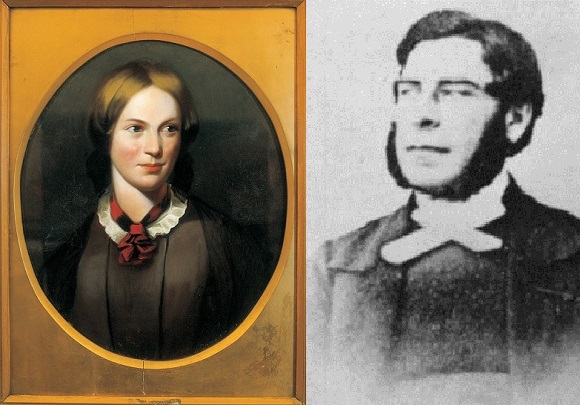

I remember Mr. Brontë as a man most tolerant to divergencies of religious conviction. Above all these memorabilia there rises before me the frail and unforgettable figure of Charlotte Brontë, who more than once stopped to speak a kindly word to the little lad who now stands a patriarch before you. I remember her funeral one Easter-tide, and some six years afterwards that of her father. These early associations, still very dear to me, were followed in after years by exceeding delight in those creations of imaginative genius which Charlotte and her sisters have left to us. Read, and many times re-read, they have often delighted the leisure hour and released the mind from the embarrassing and strenuous labours of a protracted and industrial career…

I am no authority in literary criticism but I do think, and I have always thought, that the realistic art of the Brontës makes unique appeal, and interprets itself with peculiar vividness to those whose nativity was amongst the scenes they have so graphically portrayed. I humbly stand in the ranks of the unnumbered and world-wide multitude who have found not only delight but inspiration from these sisters, who, encumbered with many adversities, rose to such great and shining heights of endeavour and discovered to the world their extraordinary literary powers. Those gifts, matured within these walls, and under the wide horizon of the Haworth Moor, have made of our little moorland village a shrine to which pilgrims from many lands wend every year their way”…

Out of these solitudes, far removed, from the vigorous and inspiring lives of the cities, there shone forth the luminous genius of three illustrious women. The presentation of these title deeds is to me an act of homage, alike to their genius, and to the nobility of their courageous lives.’

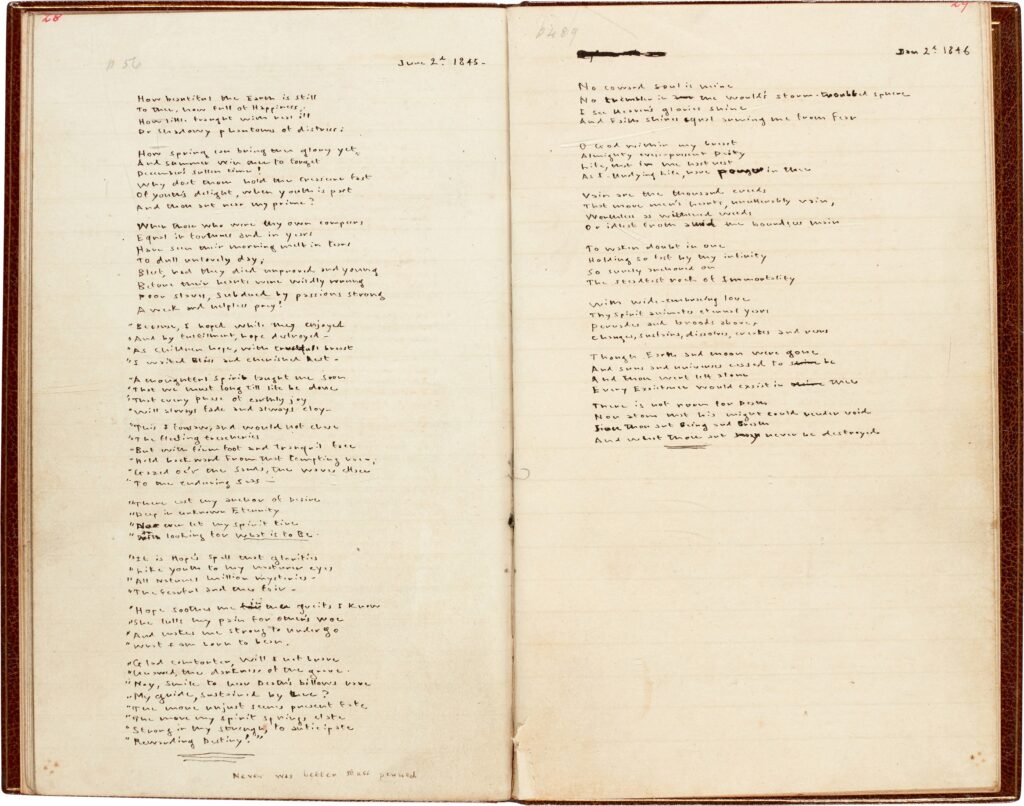

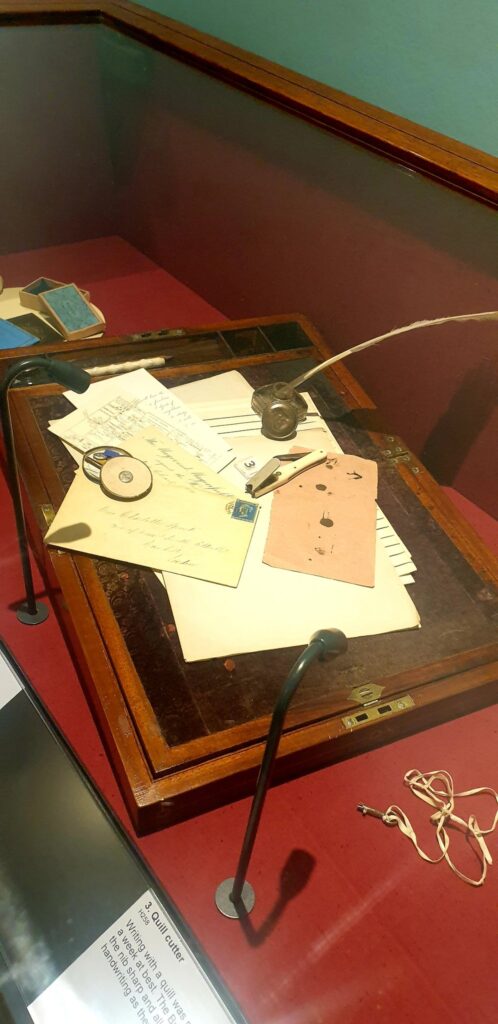

A beautiful account, and the Brontë Parsonage Museum is just as breathtaking today. I was there on Friday, and it now owes special thanks to another great benefactor. There are some exhibits that I have never seen on display before – and some of them come thanks to the beneficence of Sir Leonard Blavatnik, who saved many Brontë items for the nation recently when they were at risk of being auctioned and never seen again.

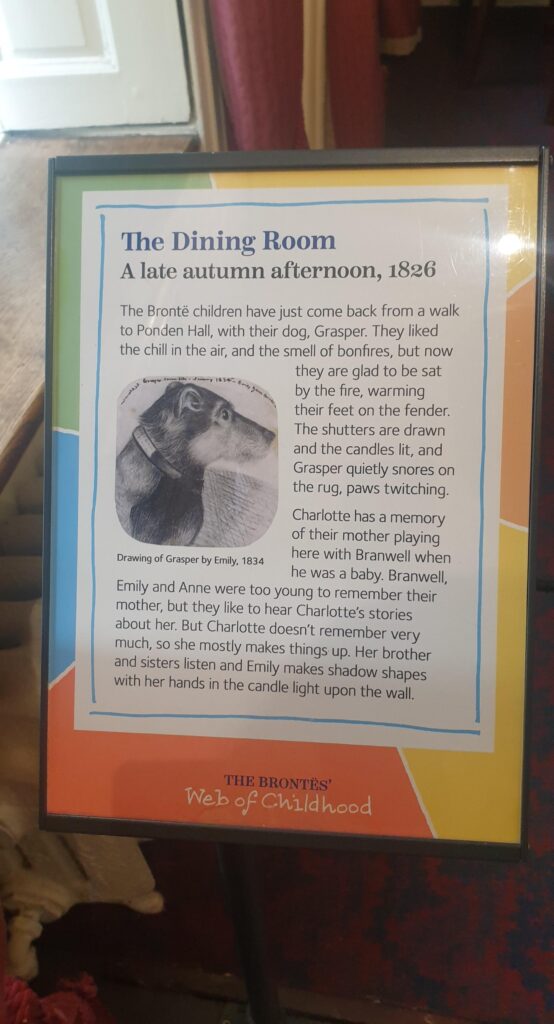

Next week I will bring you a report of this year’s new Brontë exhibition, ‘Web Of Childhood’, but for now I present some of the pictures I took this week of some of the ground floor rooms within the parsonage.

I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post, and I hope you have a sunny happy week, wherever you are.