In my nine years of creating this blog my aim has always been to create a tribute to Anne Brontë and her family, a Brontë remembrance. In today’s post we’re going to look at two Brontë poems dealing with remembrance, as well as looking ahead to a new way in which I will be remembering the Brontës, their lives and the incredible literary legacy they’ve left.

First, let us look at one of Emily Brontë’s greatest poems – titled ‘Remembrance’ it has become known for its first words, ‘Cold in the earth’. F. R. Leavis, the legendary 20th century literary academic, gave it his unstinting praise saying: ‘Emily Brontë has hardly yet had her full justice as a poet… her Cold In The Earth is the finest poem in the 19th century part of The Oxford Book Of English Verse.’

“Cold in the earth – and the deep snow piled above thee,

Far, far removed, cold in the dreary grave!

Have I forgot, my only Love, to love thee,

Severed at last by Time’s all-severing wave?

Now, when alone, do my thoughts no longer hover,

Over the mountains, on that northern shore,

Resting their wings where heath and fern-leaves cover,

Thy noble heart forever, ever more?

Cold in the earth – and fifteen wild Decembers,

From those brown hills, have melted into spring:

Faithful, indeed, is the spirit that remembers,

After such years of change and suffering!

Sweet Love of youth, forgive, if I forget thee,

While the world’s tide is bearing me along;

Other desires and other hopes beset me,

Hopes which obscure, but cannot do thee wrong!

No later light has lightened up my heaven,

No second morn has ever shone for me;

All my life’s bliss from thy dear life was given,

All my life’s bliss is in the grave with thee.

But, when the days of golden dreams had perished,

And even Despair was powerless to destroy,

Then did I learn how existence could be cherished,

Strengthened, and fed without the aid of joy.

Then did I check the tears of useless passion –

Weaned my young soul from yearning after thine;

Sternly denied its burning wish to hasten,

Down to that tomb already more than mine.

And, even yet, I dare not let it languish,

Dare not indulge in memory’s rapturous pain;

Once drinking deep of that divinest anguish,

How could I seek the empty world again?”

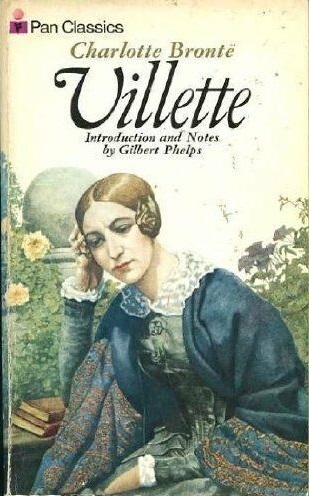

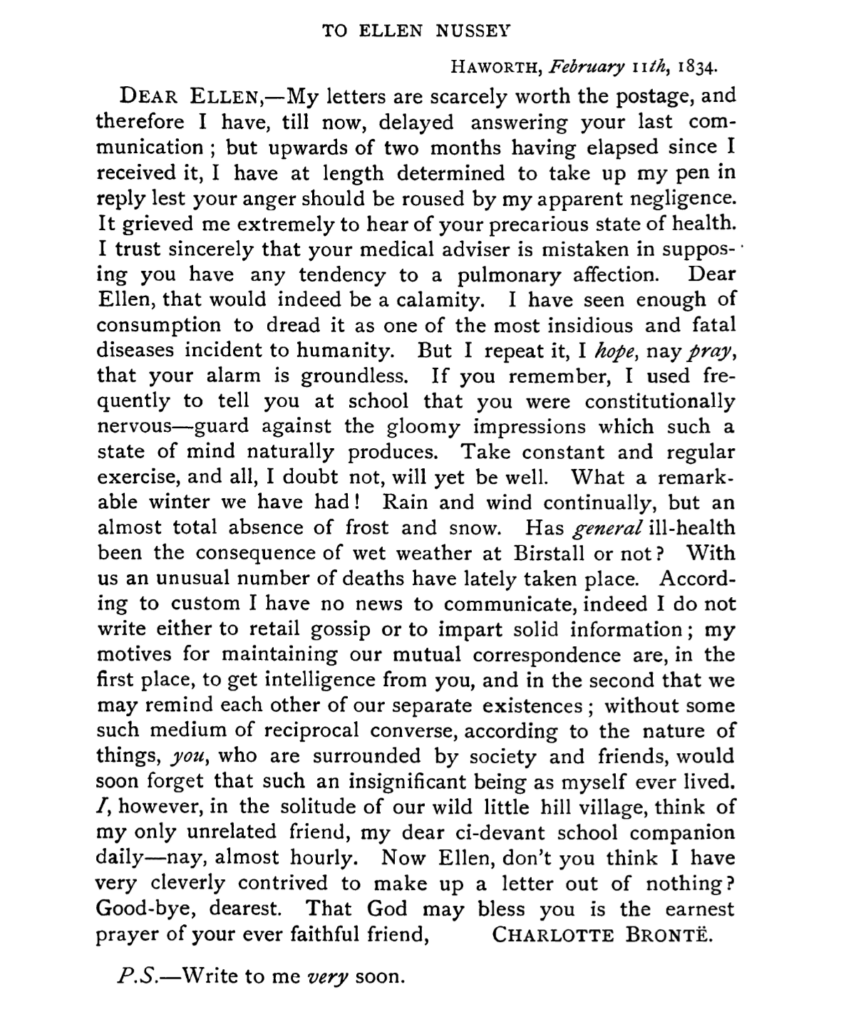

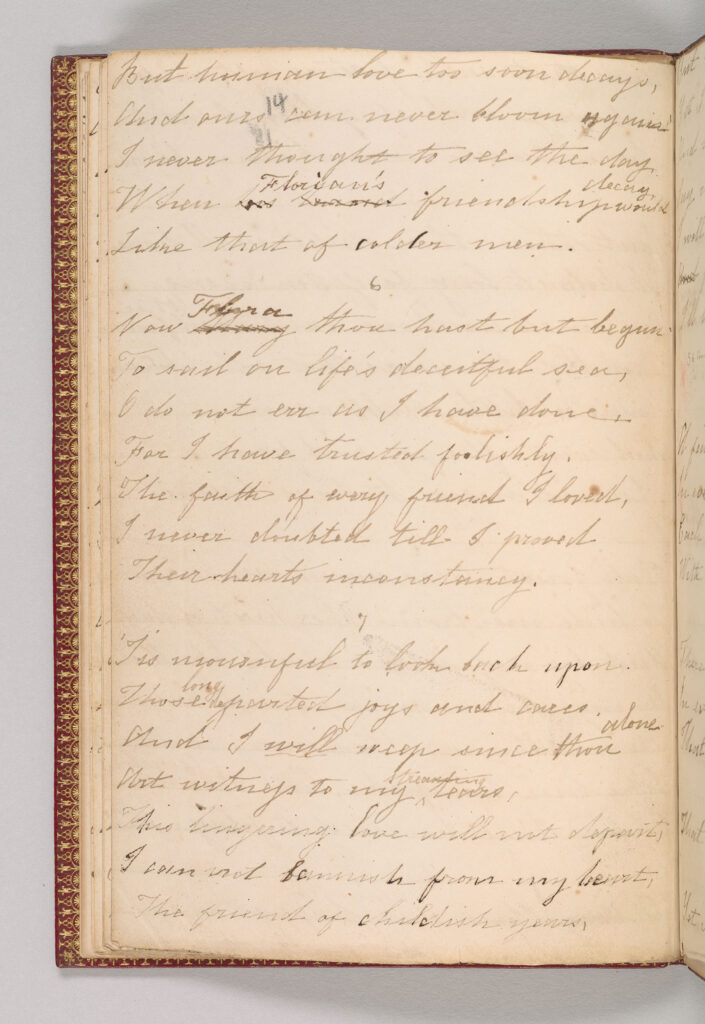

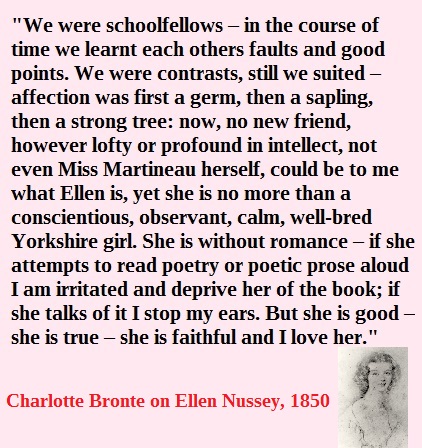

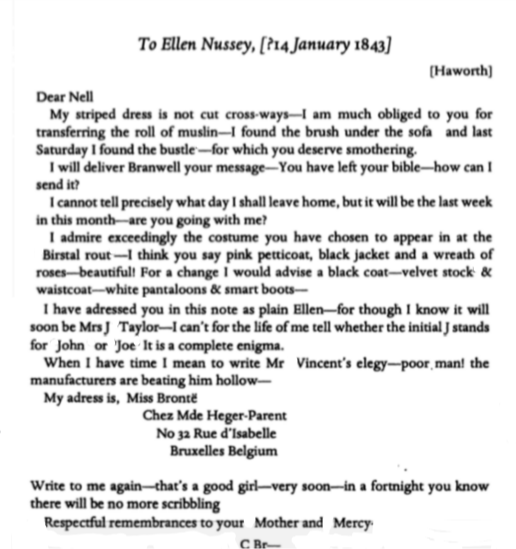

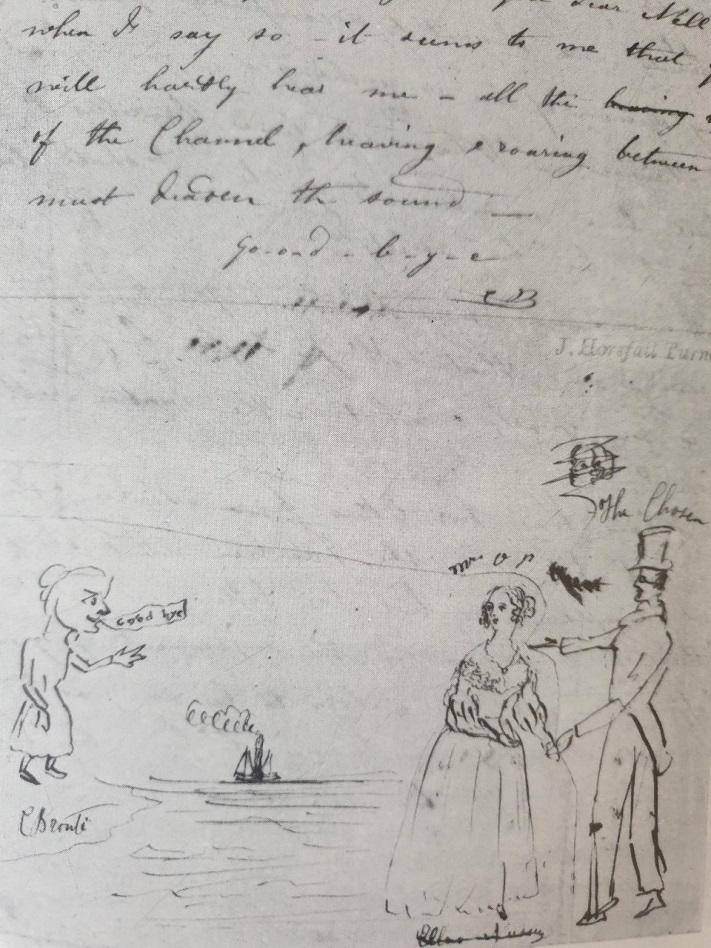

Remembrance was also on the mind of Charlotte Brontë in her poem entitled ‘Parting’:

“There’s no use in weeping,

Though we are condemned to part:

There’s such a thing as keeping

A remembrance in one’s heart:

There’s such a thing as dwelling

On the thought ourselves have nurs’d,

And with scorn and courage telling

The world to do its worst.

We’ll not let its follies grieve us,

We’ll just take them as they come;

And then every day will leave us

A merry laugh for home.

When we’ve left each friend and brother,

When we’re parted wide and far,

We will think of one another,

As even better than we are.

Every glorious sight above us,

Every pleasant sight beneath,

We’ll connect with those that love us,

Whom we truly love till death!

In the evening, when we’re sitting

By the fire perchance alone,

Then shall heart with warm heart meeting,

Give responsive tone for tone.

We can burst the bonds which chain us,

Which cold human hands have wrought,

And where none shall dare restrain us

We can meet again, in thought.

So there’s no use in weeping,

Bear a cheerful spirit still;

Never doubt that Fate is keeping

Future good for present ill!”

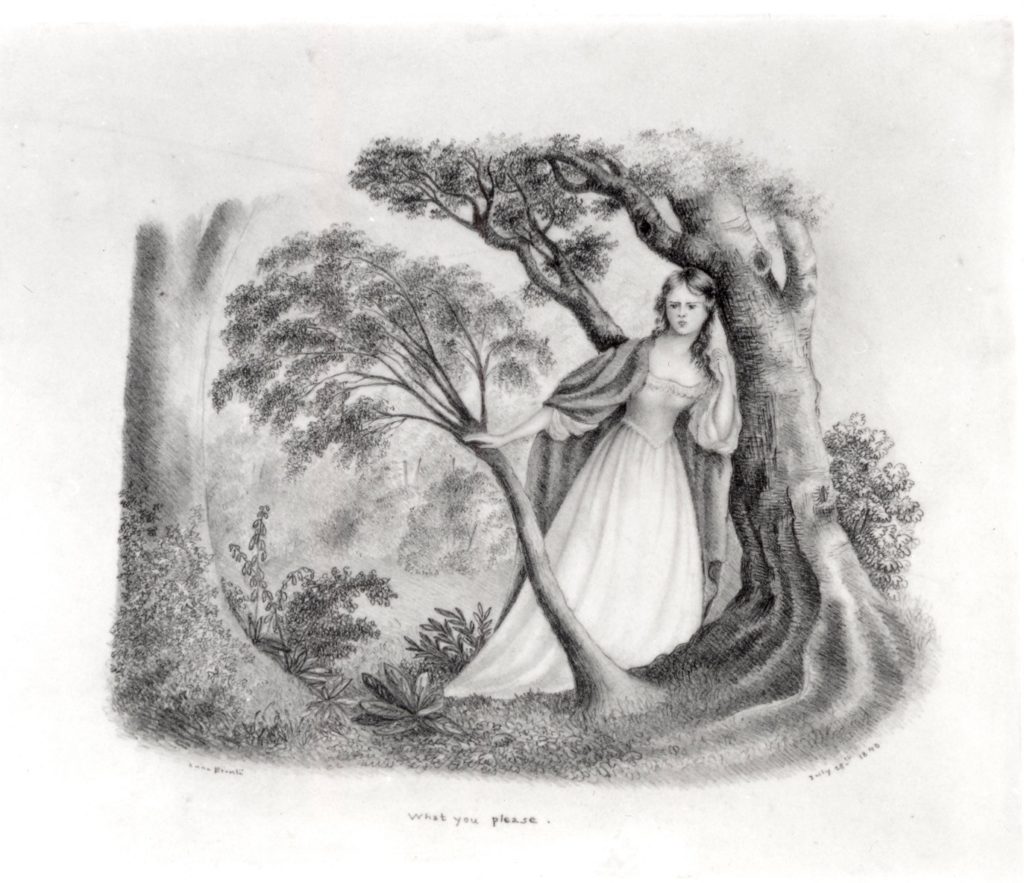

We don’t have a ‘remembrance’ from Anne Brontë, but we do have her mournful ‘A Reminiscence’:

“Yes, thou art gone ! and never more

Thy sunny smile shall gladden me ;

But I may pass the old church door,

And pace the floor that covers thee.

May stand upon the cold, damp stone,

And think that, frozen, lies below

The lightest heart that I have known,

The kindest I shall ever know.

Yet, though I cannot see thee more,

‘Tis still a comfort to have seen ;

And though thy transient life is o’er,

‘Tis sweet to think that thou hast been ;

To think a soul so near divine,

Within a form so angel fair,

United to a heart like thine,

Has gladdened once our humble sphere.”

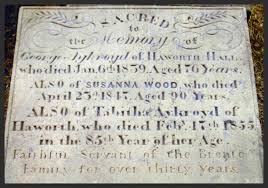

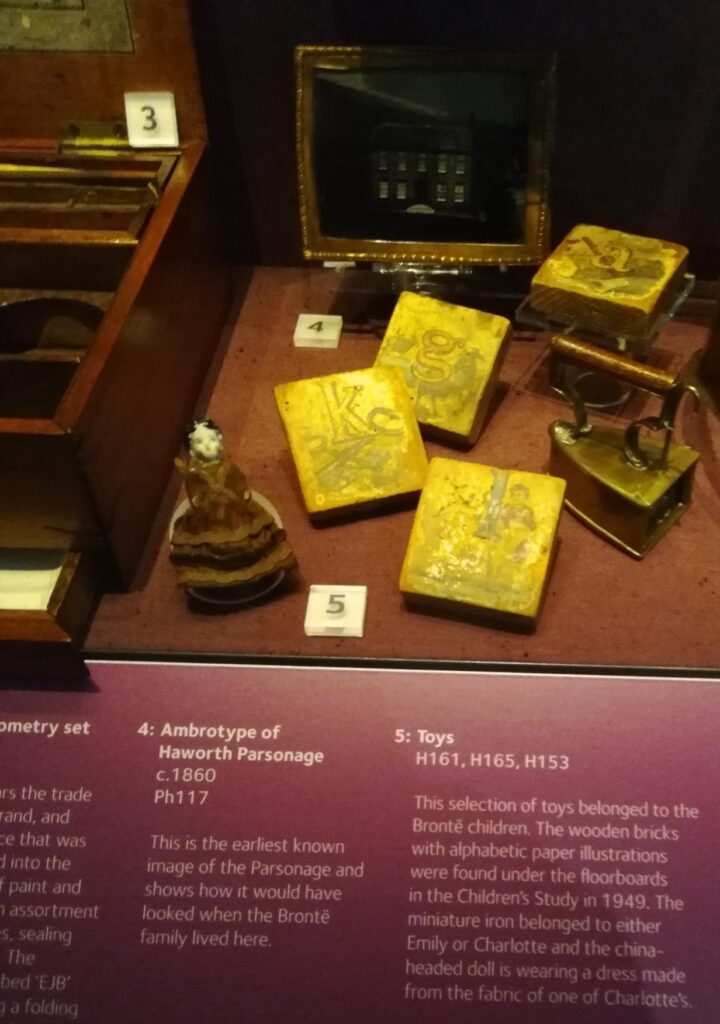

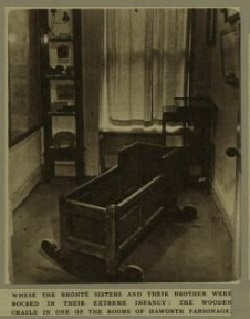

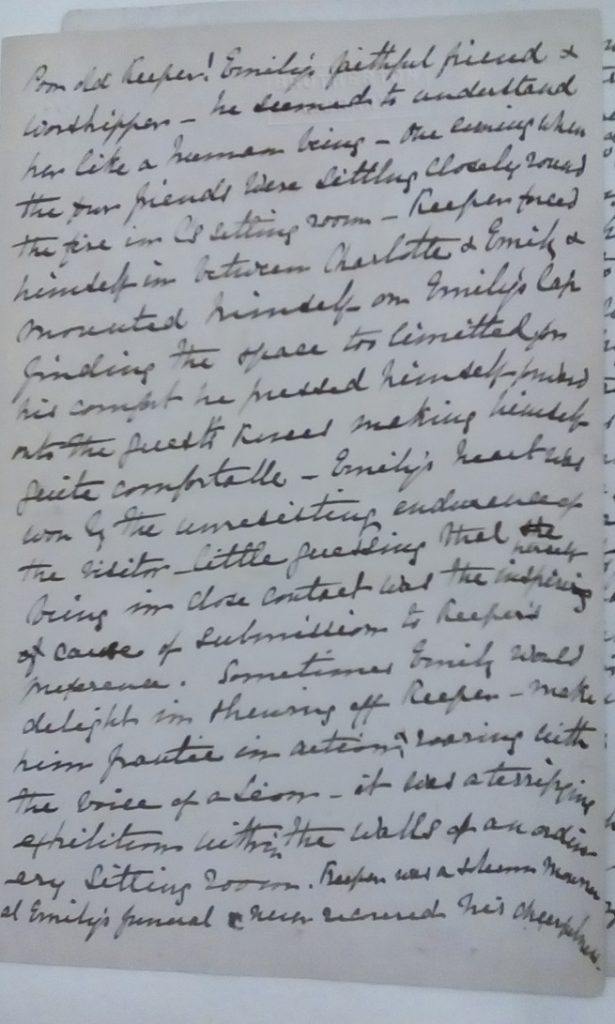

The Brontës knew the importance of remembrance, and we know how important it is to remember the Brontës. They weren’t simply a collection of sublime novels and poems, they were a living, breathing family with an incredible story of their own. A family who faced a succession of challenges and heartaches, triumphed against all the odds, yet finally succumbed to the ultimate tragedy.

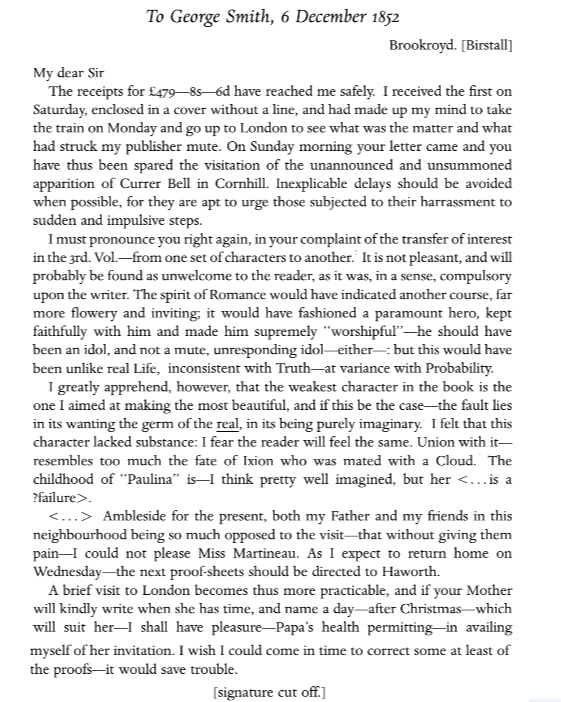

It is this incredible story that I will be telling in my new podcast ‘The House Of Brontë’, coming later this year. It will be available on Apple, Spotify, YouTube and more, and across a series of episodes I will tell the Brontë story from beginning to end – helped by some special guests who give unique insights into this endlessly fascinating family.

I first posted the above trailer on my Twitter feed yesterday, and was blown away by the positive response; in one day it’s had over 27,000 views and it’s clear that there’s still a lot of Brontë love out there!

If you have any suggestions for the podcast, or if you’d like to be a guest on the podcast, please do contact me.

If you run a business, or know a business, who would like to sponsor or support ‘The House Of Brontë’ podcast please drop me a line too – it would be great to hear from you.

I’ll bring you more news once launch day for the podcast approaches, but in the meantime I hope you will join me again next week for another new Brontë blog post.