In last week’s blog we looked at the life of Ellen Nussey and her friendship with Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Today we’ll examine her role in the preservation and dissemination of the Brontë story, and her life after the death of the three sisters she loved.

Ellen and Charlotte Brontë were close friends from the moment they met as teenagers at Roe Head School, Mirfield, in January 1831, but there was one moment of interruption in their relationship. Charlotte accepted a proposal from her father’s assistant curate Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1854, having rejected him in December 1852, and the acceptance created a rift with Ellen.

The cause of this rift can never be ascertained with any certainty, was it jealousy, disappointment, or more? Some have said that Charlotte and Ellen may have had an agreement that they would grow old together as old maids, and Ellen saw Charlotte’s engagement as a betrayal.

The two women had corresponded daily for years, but that came to a sudden end. Eventually they were reconciled, and Ellen Nussey acted as Charlotte’s bridesmaid in her marriage to Arthur on 29 May 1854. Nevertheless it seems that Ellen never liked Arthur, and later referred to him as a ‘wicked man who was the death of dear Charlotte.’

This seems to have been a harsh judgement, as Charlotte was certainly enamoured of her husband, but in one sense Ellen was right as it was Charlotte’s pregnancy that led her to die of hyperemesis gravidurum (excessive morning sickness) less than a year into her marriage.

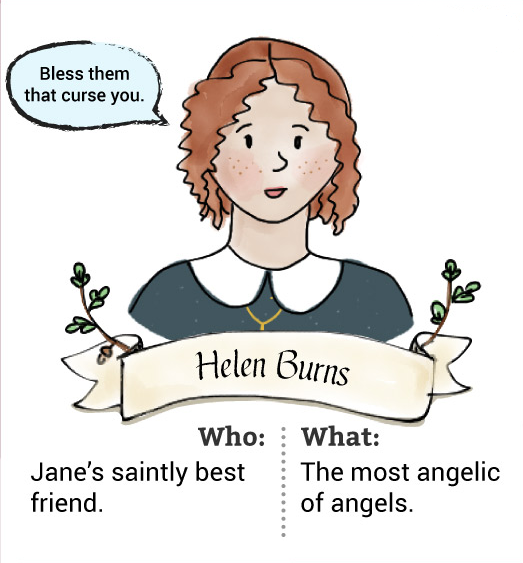

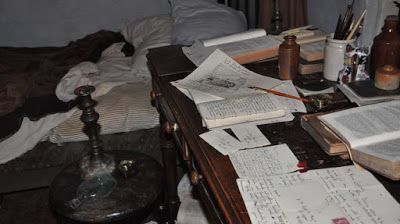

With Charlotte’s death in 1855 the line of six Brontë siblings came to an end, and both Arthur and Ellen were determined to preserve their reputation – but in very different ways. Even whilst Charlotte was alive, Arthur had urged her to impress upon Ellen that she must burn her letters after reading them, describing her lively missives as ‘dangerous as Lucifer matches.’ Charlotte wrote to inform Ellen that she would be unable to write to her unless she agreed to this request, but thankfully for us all she resisted the command.

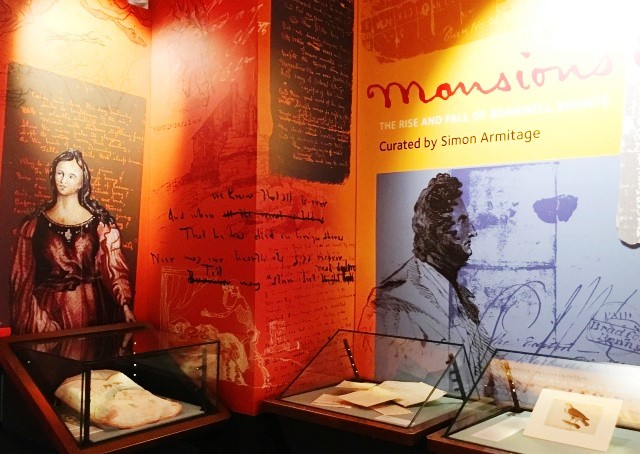

Charlotte Brontë’s letters are beautifully written, and very revealing of her innermost thoughts as well as her everyday life. They are also the most numerous and important source of information on the Brontë sisters that we have, and the vast majority that are now known to exist were written to Ellen Nussey. We have over 350 letters from Charlotte to Ellen, detailing everything from her relationship with Branwell, her depression after the deaths of Emily and Anne, to her taste in literature, her thoughts on politics, and how she came to be published. In short, Ellen’s collection of letters bring the Brontës to life for us, but that would all have been lost if Arthur’s exhortations before and after Charlotte’s death had been heeded.

The letters from Charlotte to Ellen were also the basis for the first biography of Charlotte Brontë, by her friend and brilliant author Elizabeth Gaskell, and they have formed the cornerstone for every Brontë biography written since. Ellen was happy to lend the letters to Mrs Gaskell, quite rightly, but unfortunately she also put her trust in some people who were less than reliable.

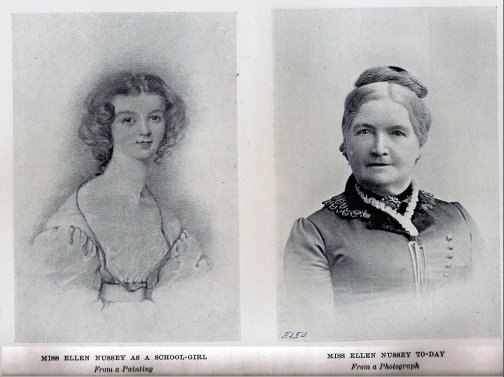

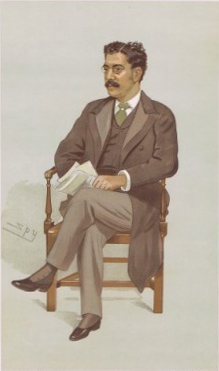

Ellen lived to the age of 80 and never married, but she was never short of company because her friendship with the Brontës made her famous in her own lifetime. Brontë fans would often visit her at Moor Lane House in Gomersal. Visitors include the American artist Frederic Yates who painted a wonderful portrait of Ellen Nussey as an old woman. Ellen’s visitors were sure to be regaled with glorious tales of the Brontës, and many of them also left with a memento of Charlotte, Emily or Anne that she had passed onto them.

Some exploited this generosity, and in particular a man named Clement Shorter. Shorter was made the first President of the Brontë Society, a move that the Society greatly regrets today as with hindsight he is clearly a villain of the Brontë story. Shorter worked in cahoots with a man named Thomas Wise, then esteemed a great literary collector and preserver but later imprisoned as a fraud and forger.

In the late 1880s they began to schmooze the now elderly Ellen, offering her £125 for the letters that they claimed they would preserve for posterity and use for a new biography of Charlotte from which Ellen would receive two thirds of the profit. In actuality, they were selling the letters at auction and to collectors, many in the United States of America, at a huge profit.

In these last years of her life, Ellen was in effect robbed of the letters she held so dear, and we have been damaged by Shorter and Wise too. Many of the letters and objects that they took from Ellen by their sharp practice remain in private collections, the whereabouts of some unknown, although others have been bought by the Brontë Parsonage Museum or returned voluntarily.

One thing they could not steal from Ellen, however, were her memories. And they can never take from Ellen the honour and praise she deserves from us, for her friendship and loyalty to the Brontë sisters in their lifetime and after their death.