There are many routes into having a book published today, as I found at a talk at Sheffield’s Off The Shelf literary festival yesterday, but that was also true at the time that the Brontë sisters were writing. One of the little known facts about the Brontës is that they initially had to pay to have their own work published, and here’s how it came about:

By 1845, the Brontë siblings had hit a low point. Anne Brontë at least had proved that she could function in the outside world by completing more than five years as a governess, demonstrating the equitable temperament that both Charlotte and Emily found hard to sustain. In the summer of 1845 however she suddenly handed in her notice at Thorp Green Hall and quit. In a diary paper written at this time she reveals the reason why:

“I was then at Thorp Green, and now I am only just escaped from it. I was wishing to leave it then, and if I had known that I had four years longer to stay how wretched I should have been; but during my stay I have had some very unpleasant and undreamt-of experiences of human nature.”

At least one source of these unpleasant experiences was her brother Branwell. Anne was always prepared to give people a second or third chance, and so she found her brother a job as governor with her employers the Robinson family. Branwell wasted no time in falling in love with his employer Linda Robinson, and of course when a young man falls in love with a middle aged woman called Mrs. Robinson things graduate. It seems that Branwell and Mrs. Robinson had an affair, and it was this indignity that proved the final straw for Anne.

By 1845, Emily and Charlotte Brontë were also back home at their familiar Haworth parsonage. They had been away in Brussels, ostensibly to learn the languages that could help them set up their own school, the Misses Brontë Establishment. All that Charlotte learned was that she loved her married professor, Monsieur Heger, and the plans for the school soon foundered.

The Brontë girls had hit a nadir. By now all in their twenties, they had failed in their attempts to be teachers and governesses; what could they do now to secure a future for themselves? It was then that fate intervened, as described by Charlotte:

“One day, in the autumn of 1845, I accidentally lighted on a manuscript volume of verse in my sister Emily’s handwriting. Of course, I was not surprised, knowing that she could and did write verse: I looked it over, and something more than surprise seized me, – a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, nor at all like the poetry women generally write. I thought them condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear, they also had a peculiar music – wild, melancholy, and elevating.”

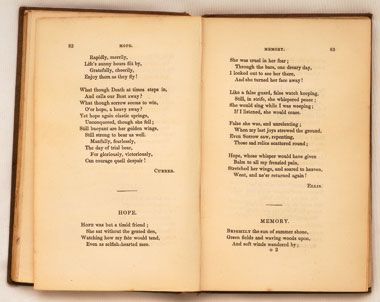

Emily was furious at this discovery, an intensely shy woman she resented anyone having access to her inner thoughts set down in writing, especially as she may have suspected that Charlotte’s discovery of them was less ‘accidental’ than she made out. Anne stepped into the fray, producing her own poetry and suggesting that the girls could work on a poetry collection together, just as they had written collaboratively as children. Not wishing to turn against her beloved sister Anne, Emily relented – and the result was ‘Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell’.

Now the sisters had compiled their book, and chosen male sounding pseudonyms to hide their identities, they had to find a publisher. This, as many writers of poetry and prose today find out, was very difficult. After a procession of rejections, the ‘Bells’ received an offer from a specialist poetry publisher called Aylott & Jones. They agreed to publish the work at the sisters’ own expense. Charlotte, Emily and Anne had recently received an inheritance from their Aunt Branwell, and so confident in their own ability they took the plunge and paid £31 10s to see their work in print. That may not sound a lot, but it was in fact almost two years wages for a governess.

After all their hard work they famously sold two copies, but the writing bug, the scribblemania, had taken hold and undeterred the Brontë sisters decided to turn to prose instead – leading to the incredible novels that we know and love today.

In effect then, the Brontë’s first foray into print was via what some people today call ‘vanity publishing’, that is paying for the work to be published rather than the publisher paying them. For the Brontës, and for us, it paid off eventually as it led to their novel writing, but it’s fitting that one of the poems Anne Brontë chose to include in this initial collection was entitled ‘Vanitas Vanitatum, Omnia Vanitas’ or ‘Vanity, vanity, all is vanity’. Here it is in full, and remember that if you wish to see your work in print, don’t be discouraged – after all, the Brontës weren’t:

“In all we do, and hear, and see,

Is restless Toil and Vanity.

While yet the rolling earth abides,

Men come and go like Ocean tides;

And ere one generation dies,

Another in its place shall rise;

That, sinking soon into the grave,

Others succeed, like wave on wave;

And as they rise, they pass away.

The sun arises every day,

And, hastening onward to the West,

He nightly sinks, but not to rest:

Returning to the eastern skies,

Again to light us, he must rise.

And still the restless wind comes forth,

Now blowing keenly from the North;

Now from the South, the East, the West,

For ever changing, ne’er at rest.

The fountains, gushing from the hills,

Supply the ever-running rills;

The thirsty rivers drink their store,

And bear it rolling to the shore,

But still the ocean craves for more.

‘Tis endless labour everywhere!

Sound cannot satisfy the ear,

Light cannot fill the craving eye,

Nor riches half our wants supply;

Pleasure but doubles future pain,

And joy brings sorrow in her train;

Laughter is mad, and reckless mirth —

What does she in this weary earth?

Should Wealth, or Fame, our Life employ,

Death comes, our labour to destroy;

To snatch the untasted cup away,

For which we toiled so many a day.

What, then, remains for wretched man?

To use life’s comforts while he can,

Enjoy the blessings Heaven bestows,

Assist his friends, forgive his foes;

Trust God, and keep his statutes still,

Upright and firm, through good and ill;

Thankful for all that God has given,

Fixing his firmest hopes on heaven;

Knowing that earthly joys decay,

But hoping through the darkest day.”

What an astounding story one that should resonate with all people trying to succeed in any endeavor.Where ever you may be situated what little wealth you may have the power of desire can and will force you thru to success.Never give in to the negative know that forcing the mind always to view the possibilities will eventually bring you to the pinnacle of success.This outlook has never and never will fail! Peter beames author of “the boy who rode clouds”