Haworth is a beautiful, magical place at this time of year, but its steep Main Street (known as Kirkgate when the Brontës first arrived there in 1820) can also be treacherous in icy conditions. The road is cobbled to help hooves and feet cling onto it, so those in the know walk down the road rather than on the pavements. Even so, it’s easy to slip, and one winter’s morning in December 1836 that’s exactly what happened to a pivotal character in the lives of Anne Brontë and her family: Tabby Aykroyd.

With a large family and a busy parish to look after, Patrick Brontë needed some hired domestic help in his Parsonage. At Thornton the Garrs sisters, Nancy and Sarah, had fulfilled the role, but by 1824 Patrick and Aunt Branwell decided that a more mature woman would be an asset in the children’s upbringing.

Tabitha Aykroyd, always known by the shortened form of Tabby, entered the Parsonage as the new servant in 1824, and she would fulfil the roles of cook, cleaner, and crucially storyteller, from that day on. Little is known of her life before she entered the Haworth Parsonage, except that she was unmarried and had two sisters Rose and Susannah, and that she was born in approximately 1771, putting her in her early fifties when she moved in with the Brontës. For many years she was the only live in servant, although in later years the younger servant Martha Brown, daughter of the sexton John, also moved in.

Patrick and Aunt Branwell would have given careful consideration to their choice of housekeeper, and so we can certainly assume that Tabby already had experience in a similar role, and she was probably well known to them as a frequenter of St. Michael and All Angels church.

Tabby seems to have been a forthright no-nonsense Yorkshire woman of the type still readily found today, but also typically she could be very warm and loving. Elizabeth Gaskell, who had met Tabby, described her thus:

‘She abounded in strong practical sense and shrewdness. Her words were far from flattery; but she would spare no deeds in the cause of those whom she kindly regarded.’

A strong bond formed between Tabby and the children, although we have one story of how the young Brontës delighted in frightening her on one occasion. They were acting out a play, as they liked to do, and in this particular one they must have been pretending to be demons or monsters. So good were they at this role that Tabby fled the Parsonage in terror and ran to her nephew William Wood, a coffin maker. Branwell’s friend and biographer Francis Leyland described what she said:

‘William! William! Yah mun goa up to Mr Brontë’s for aw’m sure yon chiller’s all gooin mad, and I dar’nt stop ith house ony longer wi’em; and aw’ll stay here woll yah come back!’

William went to the Parsonage and was greeted with a great cackle of laughter from the Brontë children, delighted at how successful their trick had been.

Nevertheless the children doted on Tabby, who had become a grandmother-like children to them. She not only baked them cakes that they loved, and gave them the hugs and praise that any young child needs, she also told them tales of Yorkshire folklore that had been passed down through the centuries: tales that the Irish Patrick and Cornish Aunt Branwell would have been oblivious to.

Tabby, in the broad Yorkshire dialect that we encountered above, would tell them tales of ghosts, goblins and gytrashes, and of fairies, or feys as they were called in that area, who roamed the moors and would sometimes swap children for fey changelings. These wild stories enthralled Anne, Charlotte and especially Emily, and the influence upon Wuthering Heights is plain to see (where Tabby is an obvious model for the narrator Nelly Dean).

Tabby was around 65 when she slipped over on the Haworth ice, and her leg was badly broken leaving her unable to carry out her duties, temporarily at least. Aunt Branwell insisted that with finances tight as always Tabby had to be removed from her post, but the Brontë teenagers were equally vehement. They insisted that Tabby was part of the family, and not simply someone who could be removed when no longer in full health, and they even refused to eat until the decision had been made that Tabby could stay.

Their kindness won out, and Tabby remained at the Parsonage even though her mobility would be limited for the rest of her life. Emily Brontë stepped up to the plate, taking on many of the domestic duties that Tabby had carried out, and doing them excellently.

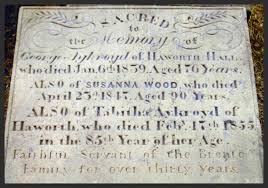

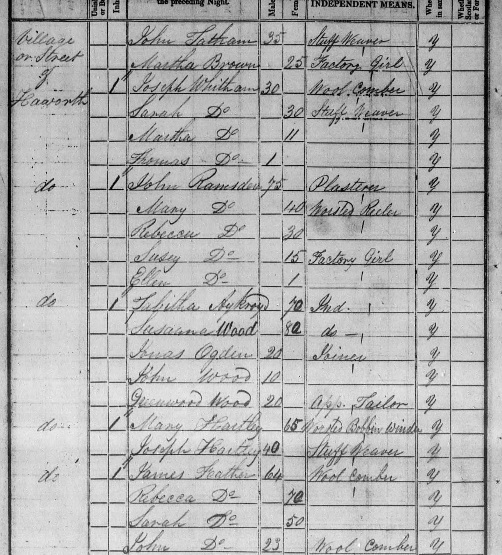

In 1839 Tabby moved in with her widowed sister Susannah, and it is at their shared house on Newell Hill that she appears in the 1841 census of Haworth. Nevertheless we know that by 1842 she was back at the Parsonage, and she would remain there until her own death in February 1855, having outlived all the children except Charlotte Brontë who herself had only months to live at the time.

Tabby is buried just over the wall from the Brontë Parsonage garden, a fitting tribute to the good and faithful servant who did so much to encourage the Brontë’s great works, and to bring happiness to the lives of the Brontë siblings.