The Royal Society of Literature are currently engaged in trying to discern the nation’s favourite second novel. There are some real classics on the list, but of course our eyes are drawn to the two Brontë novels on there: Shirley by Charlotte Brontë and The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë (if only Emily had managed to complete her fabled second work!).

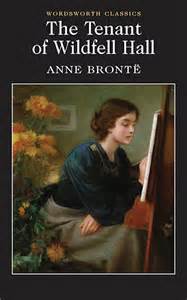

You can only vote once, so just which novel should you support? Both books are works of genius, and both Anne and Charlotte thought their second novel was their greatest work. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is gaining in reputation all the time, partly because it’s a very modern novel in the way that it deals with modern themes such as marital abuse, women’s rights, alcoholism and addiction. It is also, as we would expect from a wordsmith as brilliant as Anne, superbly written. Every word serves a purpose, and that purpose as Anne revealed in her famous preface to the second edition was as follows:

‘My object in writing the following pages, was not simply to amuse the Reader, neither was it to gratify my own taste, nor yet to ingratiate myself with the Press and the Public: I wished to tell the truth, for truth always conveys its own moral to those who are able to receive it.’

Anne succeeded completely in this laudable aim, so much so that some critics called it a brutal novel that was unfit for women to read. Nevertheless, Anne also infused it with moments of light and laughter not often associated with Brontë novels – particularly in the character of Fergus, the pompous young man who likes to play tricks on others but often ends up being the victim himself.

There is also, for a novel dealing with such shocking themes, a tenderness running through The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall. The scene where Helen finally declares her love for Gilbert by means of a snow covered flower is wonderful and moving:

‘This rose is not so fragrant as a summer flower, but it has stood through hardships none of them could bear: the cold rain of winter has sufficed to nourish it, and its faint sun to warm it; the bleak winds have not blanched it, or broken its stem, and the keen frost has not blighted it. Look, Gilbert, it is still fresh and blooming as a flower can be, with the cold snow even now on its petals – will you have it?’

The novel, along with the sublime Agnes Grey, has cemented Anne Brontë forever as one of the greatest writers of all time, so surely it deserves your vote in the RSL survey? Wait – for Shirley is worthy of recognition too.

Shirley was, of course, the third novel Charlotte Brontë wrote, but as her first effort The Professor was published posthumously, it qualifies for the competition. I have seen many events over the last few years where scholars and authors debate which was Charlotte’s best book – and the choice is always between Jane Eyre and Villette. Unfairly neglected – in my opinion, Shirley is Charlotte’s greatest achievement.

Taking a leaf out of Anne’s book, Charlotte decided to inject some contemporary truths into her novel. The locations ring true – as it’s based in the heavy woollen area of Yorkshire she knew so well from her school days in Mirfield, and her visits to Ellen Nussey in Birstall and Mary Taylor in Gomersal.

It is a novel that ostensibly looks back at the Luddite riots earlier in the century, the loom smashing riots that frequently turned deadly in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Shirley has a hint of menace running throughout it, and a hint of a message as well, as Charlotte shows that we need to value people more than machines, but also that we need to see people as they really are not just what they are perceived to represent.

It was a timely message, for Charlotte was using the story of the Luddites to comment on the Chartist dissatisfaction of her time – one that again threatened to break out into violence at any time.

It is a thrilling novel certainly, but what I like most about it is that most of the protagonists in the book are based upon people she knew – from the Taylor family, to Margaret Wooler, to Arthur Bell Nicholls, they all make an appearance under assumed names (and what is wrong with that after all, Charlotte was using the assumed name of Currer Bell to write it).

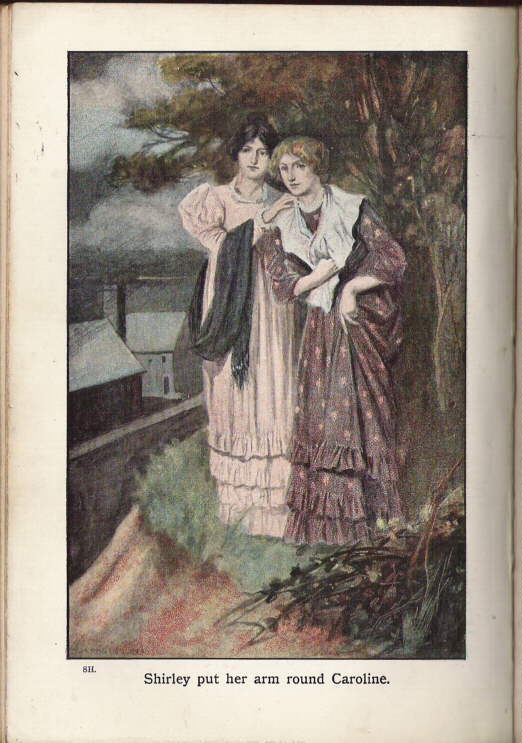

The two female leads of the novel are of particular interest to me. Shirley Keeldar herself is a portrait of Emily Brontë, proud and lovely, defiant and caring. Shirley may be the title character, but the real heroine, and featured much more within the novel, is Caroline Helstone – a loving portrait of Anne Brontë:

‘She is nice; she is fair; she has a pretty white slender throat; she has long curls, not stiff ones – they hang loose and soft, their colour is brown but not dark; she speaks quietly, with a clear tone; she never makes a bustle when moving; she often wears a gray silk dress; she is neat all over.’

Most touching to me is when Charlotte describes the close relationship that Shirley and Caroline develop.

‘Caroline’s instinct of taste, too, was like her own. Such books as Miss Keeldar had read with the most pleasure were Miss Helstone’s delight also. They held many aversions too in common, and could have the comfort of laughing together over works of false sentimentality and pompous pretension.’

Caroline, sweet, thoughtful and loyal to the last, will do anything for her beloved Shirley, even when she is asked to face the greatest danger:

‘”I am a blind, weak fool, and you are acute and sensible, Shirley. I will go with you; I will gladly go with you!”

“I do not doubt it. You would die blindly and meekly for me…”

Caroline rapidly closed shutter and lattice. “Do not fear that I shall not have breath to run as fast as you can possibly run, Shirley. Take my hand. Let us go straight across the fields.”

“But you cannot climb walls?”

“To-night I can.”

“You are afraid of hedges, and the beck which we shall be forced to cross?”

“I can cross it.”’

What is most moving to me is that Charlotte completed this novel at a time of great personal despair. Emily and Anne, Shirley and Caroline, both died while she was writing the novel. It is thought that Charlotte had planned that the Caroline character would die, of tuberculosis, only to see this happen in reality to Anne. The novel was changed, and Caroline makes a miraculous recovery and gains a happy ending. In real life Charlotte had been in powerless, but on the page at least she could save Anne, but Charlotte submitted, with tears dripping from her eyes onto the paper before her, what she had endured during the final illness of her youngest sister:

‘Not always do those who dare such divine conflict prevail. Night after night the sweat of agony may burst dark on the forehead; the supplicant may cry for mercy with that soundless voice the soul utters when its appeal is to the Invisible. ‘Spare my beloved’, it may implore. ‘Heal my life’s life. Rend not from me what long affection entwines with my whole nature. God of heaven, bend, hear, be clement!’ And after this cry and strife the sun may rise and see him worsted. That opening morn, which used to salute him with the whisper of zephyrs, the carol of skylarks, may breathe, as its first accents, from the dear lips which colour and heat have quitted, ‘Oh! I have had a suffering night. This morning I am worse. I have tried to rise. I cannot. Dreams I am unused to have troubled me.’

Then the watcher approaches the patient’s pillow, and sees a new and strange moulding of the familiar features, feels at once that the insufferable moment draws nigh, knows that it is God’s will his idol shall be broken, and bends his head, and subdues his soul to the sentence he cannot avert and scarce can bear.’

The next paragraph, a miracle, the prayers have been answered. As Charlotte knew too well, in real life it’s not that easy.

So, we are faced with a tough choice – The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall or Shirley? Team Anne or Team Charlotte. I am,of course, Team Anne, so I finally voted for The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall. I wonder if I can sneak a vote for Shirley in as well? It would be well deserved.