A representative of her Majesty’s Government this week declared Jane Austen ‘one of our greatest living writers’. Andrea Leadsom’s faux pas rightly earned her derision, as after all this week also marked the 200th anniversary of Jane’s death. On July 18th 1817, in a rented house in Winchester, Jane drew her last breath aged 41, but in her all too short life she had revolutionised the world of writing for ever. Jane not only helped secure the popularity of the novel as an art form, often seen as subservient to poetry at the time she wrote her first work, ‘Sense and Sensibility’, in 1811, she also paved the way for new generations of women writers who would follow her – and of course, chief among these to my eyes are Charlotte, Emily and Anne – the Brontë sisters.

Leadsom’s comments have caused debate not only because she seems to think that Jane Austen is ready to produce Pride and Prejudice too at the age of 241, but also because of the supremacy she gave to her writing. Some say that Jane is without a doubt our finest novelist, whereas others say that she cannot be considered as great as the Brontës. In my opinion, they are very different writers, but all four of them are worthy of veneration and admiration. In both Jane’s life and writing there are comparisons with the Brontë sisters, and startling contrasts.

Jane was after all an early nineteenth century writer who never married and lived with her family throughout her life. So far, so similar to our favourite siblings Anne, Emily and Charlotte (who, admittedly, did marry aged 38, only to succumb to the effects of excessive morning sickness and die less than a year later).

Another striking similarity between Jane Austen and the Brontës stands out: sisterly love. Emily and Anne Brontë in particular were very close, being referred to as being like inseparable twins and often seen with their arms entwined with each others, despite their two year age difference. A similar relationship existed between Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra, two years older than Jane and always by her side throughout her triumphs and set backs, and also through her final illness.

There may also be a similarity between Jane and Anne Brontë in matters of love. Anne’s writing gives us a strong hint that she was in love with her father’s assistant curate William Weightman, but his early death from cholera put an end to any hopes Anne may have held of a future for them. Jane Austen too knew love, but found it thwarted. Tom Lefroy was the prototype of Mr. Darcy, just as Weightman was the prototype of Rev. Weston in Anne’s first novel ‘Agnes Grey‘. In Jane’s case the prospect of love was ended not by death, but by a drifting apart. It seems that in both cases, Anne and Jane never loved again.

In other ways, however, Jane Austen differed markedly from the Brontës. Jane was writing earlier in the century than Charlotte, Emily and Anne, and in a century that changed so radically as the decades advanced, this made a huge difference. Jane Austen was very much a regency woman, familiar with the values and traditions of the late eighteenth century, whereas the Brontës grew up at the start of Queen Victoria’s reign, and witnessed the huge social impact brought by the industrial revolution in a way that Jane never did. As an example of this, Jane Austen travelled to London from Chawton, in Hampshire, in 1815 by horse drawn carriage. In 1848, Charlotte and Anne Brontë travelled from Keighley to London via train.

The purpose of these two meetings reveals another important difference between Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters: Jane was travelling to meet the Prince Regent, later George IV, who was a huge fan of his work; Charlotte and Anne Brontë were travelling to meet the publisher George Smith, where they would finally reveal their true identity away from the masks of Currer and Acton Bell that they had hidden behind.

Jane Austen’s writing made her famous in her lifetime, a success that Anne and Emily would never know or desire. The Brontë sisters needed money in a way that Jane never did, but they eschewed fame and preferred public anonymity, although after the death of her younger sisters Charlotte did, reluctantly, step into the limelight.

Another important distinction between Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters was their social position. Whilst the Brontës were respectable, thanks to their father Patrick’s position as a long established priest in the Church of England, they were never rich, and were solidly lower middle class, whereas Jane was from an upper middle class background. Her financial position, and her position in society, became even more secure when her brother Edward was adopted by the very wealthy Thomas Knight. Knight had no children of his own, and in 1783 chose his distant relative the 15 year old Edward Austen, afterwards Edward Austen Knight, to be his legal heir. Edward adopted a number of grand properties, including the beautiful Chawton House. He also obtained a nearby property at Chawton for Jane to live in, and it was there that she worked on some of her greatest masterpieces.

The contrast between Jane’s brother Edward and the Brontës’ brother Branwell could not be greater: Branwell seemed to be a promising talent in his own right, but there would be no wealthy patronage for him, and he died at the age of 31 after a long addiction to drink and opium.

Some have said that Jane Austen was obsessed with ‘marriage-ability’ in her novels, and obtaining or escaping matrimony is certainly her most central theme, but this was of incredible import to middle class women in Jane’s day, especially if, like the Bennets of Longbourn, they have been ‘entailed’ out of any prospect of coming into an inheritance.

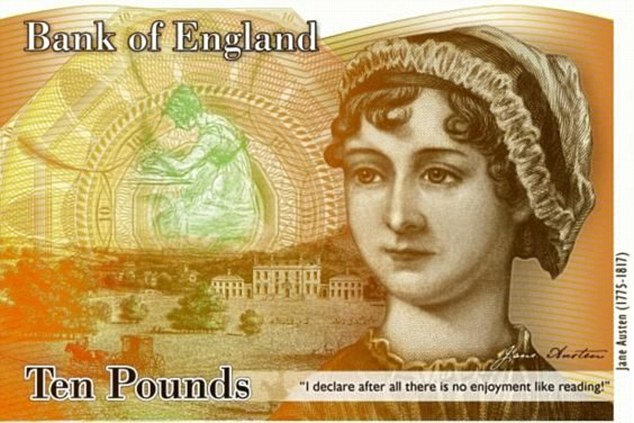

I was watching a newspaper reviewer on Sky News this week discuss the use of Jane Austen’s appearance on the new ten pound note. He said that she was a Victorian Mills & Boon writer, her works are nothing but Love Actually written a hundred years ago. I was fuming at this level of ignorance and buffoonery, from the smirking buffoon on the sofa, and I feel sorry for people who share this view and haven’t discovered the brilliance of her work. Thankfully, as the unveiling of the first ever lifesize statue of Jane in Basingstoke this week showed, there are still huge numbers of people who are moved and exhilarated by her work:

Jane Austen was, above all things, a spectacularly good writer. The pages of her novels seem to turn themselves, and they are joyous reads, even though they can also be emotional rollercoasters. They are also incredibly humorous, and contain much more comedy than you find in Brontë novels. They are also highly satirical in a way that is absent from the Brontë novels. Austen novels are set in a world of high incomes, and grand stately homes filled with servants, but Jane clinically dissects this world and often holds it up for ridicule.

In the early part of the twentieth century, the then celebrated Irish author George Moore wrote:

“If Anne Brontë had lived ten years longer, she would have taken a place beside Jane Austen, perhaps even a higher place.”

We can equally lament that Jane Austen did not live another ten years. Her novels will always be read and always be loved. While ever this planet of ours continues its restless orbit around the sun, readers will still swoon over Fitzwilliam Darcy, and his ten thousand a year, and root for Emma to put her matchmaking to one side find her Knightley. Times will change, but the novels of Jane Austen will remain timeless. For me, of course, Anne Brontë and her sisters will always occupy a position of supremacy in the writing pantheon, but there’s certainly room for Jane Austen and her novels in my affection too. It’s been wonderful to see the events in Hampshire, Bath, and beyond this week – Jane rightly being remembered, and celebrated.

I like the new bank note, even if Jane has been airbrushed a little. The quote used on the note has attracted some mockery: ‘I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading.’ This is said by Miss Bingley in ‘Pride and Prejudice’, in order to win the approval of book loving Mr Darcy. On seeing it has little effect on him, she dashes her book onto the couch and looks for something ‘more interesting’ to do. I think it’s an excellent quote for the note, even if its meaning may have passed by the Bank of England commissioners: it is, after all, an excellent example of the irony and humour that runs like a vein of gold through Jane Austen’s writing. I do think, however, that the next note should feature the Brontë sisters – after all in this age when we all strive for equality we would then have three more women on bank notes for the price of one. We have a perfect ready made quote from Anne Brontë as well, this time delivered without a hint of irony:

‘Reading is my favourite occupation, when I have leisure for it and books to read.’

Great comment. It could have covered Charlotte’s deprecatory assessment of Jane’s writing. I don’t agree with Charlotte, not at all! I wonder whether the Victorians were generally critical of what had gone before – as we have little patience with the frequently tedious and prolix 19th century prose. Cheers. Mel