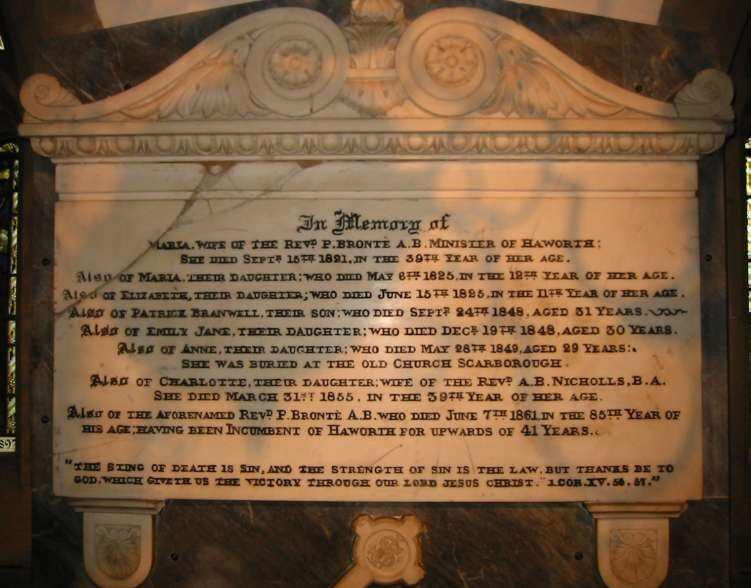

Yesterday, the 22nd of September, marked a sad anniversary in the Brontë story, as it was on that day in 1821 that Maria Brontë was buried in the vault of St. Michael and All Angels’ church in Haworth, leaving Anne Brontë and her five siblings without a mother (although Maria’s sister Elizabeth ‘Aunt’ Branwell filled that void in some ways in the years to come). Maria had died exactly a week earlier on 15th September after a long illness, but if we look closely we can still see a lot of Maria reflected in her children.

We learn from Charlotte, after she perused the letters that Maria had sent to Patrick Brontë during their courtship, that she had a fine mind which reminded her of her own:

‘It was strange now to peruse for the first time the records of a mind whence my own sprang – and most strange – and at once sad and sweet to find that mind of a truly fine, pure and elevated order. They were written to papa before they were married – there is a rectitude, a refinement, a constancy, a modesty, a sense, a gentleness about them indescribable. I wished she had lived and that I had known her.’

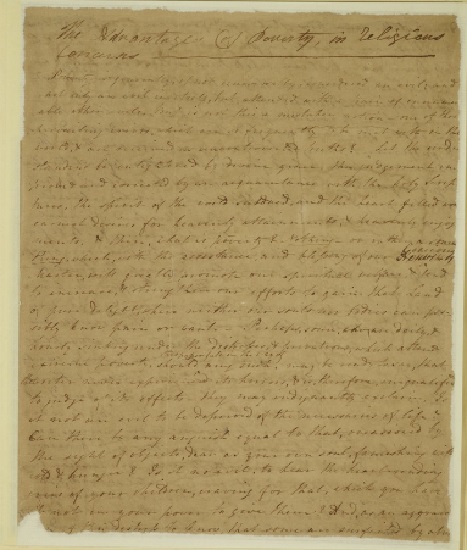

From these letters of Maria’s, we also learn that she was an excellent and expressive writer, a woman full of love but who also had a sense of humour. These qualities, I feel, are also in the writing of Anne Brontë. There is one other piece of writing that Maria has left us, a short yet remarkable essay called ‘The Advantages of Poverty in Religious Concerns.’

It’s a very revealing essay, and shows how religion and faith were central to Maria’s life, and also how highly she valued stoicism, a quality associated with both Emily Brontë and Elizabeth Brontë. Maria Branwell, as she was known before her marriage, was from a wealthy Cornish family with a very different social background to Patrick Brontë. She could have seen a match with him as unsuitable, but she valued his piety and faith much greater than his lack of wealth and private income. This too is reflected in the opening to Anne Brontë’s ‘Agnes Grey’ when Agnes reflects on the social differences between her mother and father:

‘My mother, who married him against the wishes of her friends, was a squire’s daughter, and a woman of spirit. In vain it was represented to her, that if she became the poor parson’s wife, she must relinquish her carriage and her lady’s-maid, and all the luxuries and elegance of affluence… but she would rather live in a cottage with Richard Grey than in a palace with any other man in the world.’

Anne was just one year old when her mother died, but if she had read ‘The Advantages of Poverty in Religious Concerns’ she would have found a heart and soul akin to her own. Maria begins with this proclamation:

‘Poverty is generally, if not universally, considered an evil; and not only an evil in itself, but attended with a train of innumerable other evils. But is not this a mistaken notion – one of those prevailing errors which are so frequently to be met with in the world and received as uncontroverted truths? Let the understanding be enlightened by divine grace, the judgement improved and corrected by an acquaintance with the holy Scriptures, the spirit of the world subdued, and the heart filled with the earnest desires for heavenly attainments and heavenly enjoyments, and, then, what is poverty? Nothing.’

In a moving section, particularly in the light of how Maria would all too soon have to leave her own children, she considers that people would say she couldn’t understand poverty because she had never experienced it, and that they would say:

‘Is it not an evil to be deprived of the necessaries of life? Can there be any anguish equal to that occasioned by objects, dear as your own soul, famishing with cold and hunger? Is it not an evil to hear the heart-rending cries of your children craving for that which you have it not in your power to give them? And, as an aggravation of this distress, to know that some are surfeited by abundance at the same time that you and yours are perishing for want?’

Maria’s response is that yes, this is an evil, but people can overcome even this when they have been transformed by God and the divine message. She ends her essay with the words:

‘It surely is the duty of all Christians, to exert themselves in every possible way, to promote the instruction & conversion of the Poor: and, above all, to pray with all the ardour of Christian faith, and love, that every poor man, may be a religious man.’

We can see then that Maria placed faith above all other things, and believed it was better to be poor and have faith in God, than to be wealthy and lack faith. It’s a view that some in today’s increasingly secular society would find hard to understand, but it was the driving force behind Maria’s life, and found its closest match in Anne, the one year old baby she had to leave behind. The manuscript can today be read in the Brotherton Library, Leeds. Just below Maria’s conclusion is another hand; it’s that of her late husband Patrick Brontë, a moving footnote that reveals his unending love and admiration for his wife:

‘The above was written by my dear Wife, and sent for insertion in one of the periodical publications – Keep it as a memorial of her.’

As the saying goes ‘there is no smoke without without fire.’ The smoke of the Brontë children’s prose & poetry had to have its root in the ancestral numinous vigour of parentage.

So enjoy reading your articles on the Brontë’s, thank you. And a visit to the Brotherton Library feels in the offing.